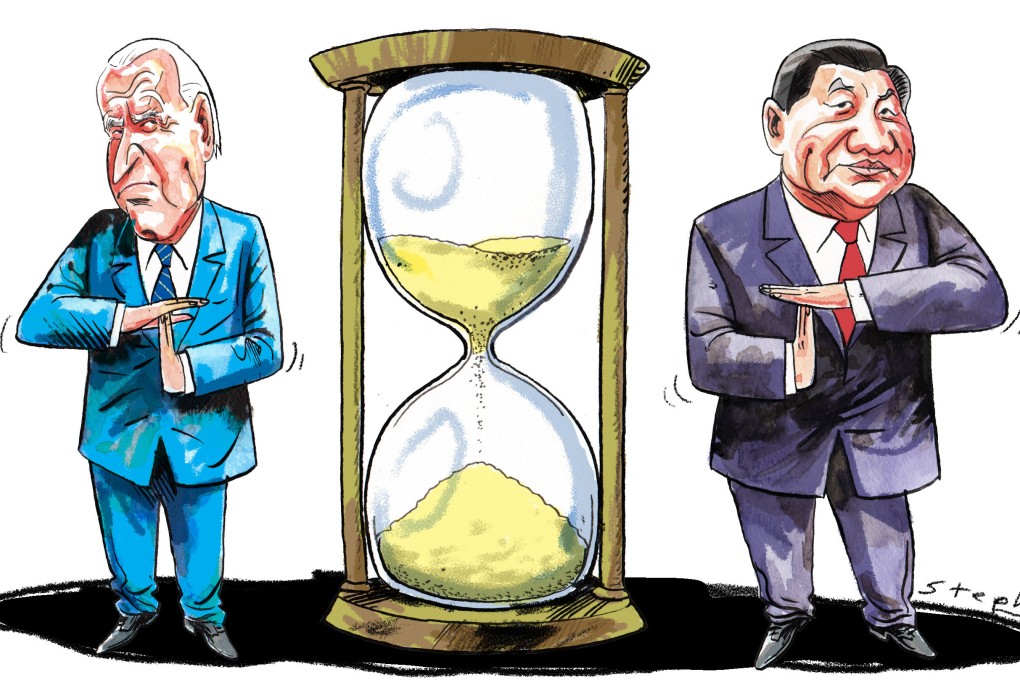

Opinion | Domestic politics is driving US and China to seek a ‘time out’ amid rising tensions

- Agreements reached on a host of contentious issues, before and after the Xi-Biden summit, were made possible by the need for both leaders to focus on domestic challenges

- Renewed engagement is especially timely between the two militaries, in light of US anxiety over Chinese advances in space and cyber technologies

What happened between March and November? American officials are quick to assert that Beijing had viewed the incoming Biden administration as a return to Obama-era policy, and needed to be disabused that Washington would be cajoled into dropping Trump-era policies. They view the change in tone and cooperation from Beijing as a result of their initial tough stance.

Normally, after recording minor advances between troubled powers, such outcomes have a thousand fathers, all proudly providing background information to favoured columnists with stories of their achievements. But not this time, when claiming progress might invite partisan allegations of softness on China.

They believe the US softened its rhetoric and restrained its behaviour because the alternative was not working. They internally take credit for standing up to America.