How dollar peg and mainland inflation policy will help Hong Kong keep price rises in check

- Hong Kong consumers will not be totally spared from rising prices as policy decisions at home and elsewhere take effect

- Even so, Beijing’s commitment to curbing inflation and the Hong Kong dollar’s reliable peg should insulate the city from the worst effects

Such tightening could lead the US dollar to outperform, pushing up dollar-denominated prices of food and energy in other currency terms. Fortunately, Hong Kong is well placed to avoid some of this upward price pressure.

In terms of transport, Citybus and New World First Bus have raised the price of journeys by another 3.2 per cent this year under the final phase of a previously agreed government-approved fare adjustment plan.

Meanwhile, people in Hong Kong are receiving less money under the government’s public transport subsidy scheme that is operated in conjunction with stored-value Octopus cards.

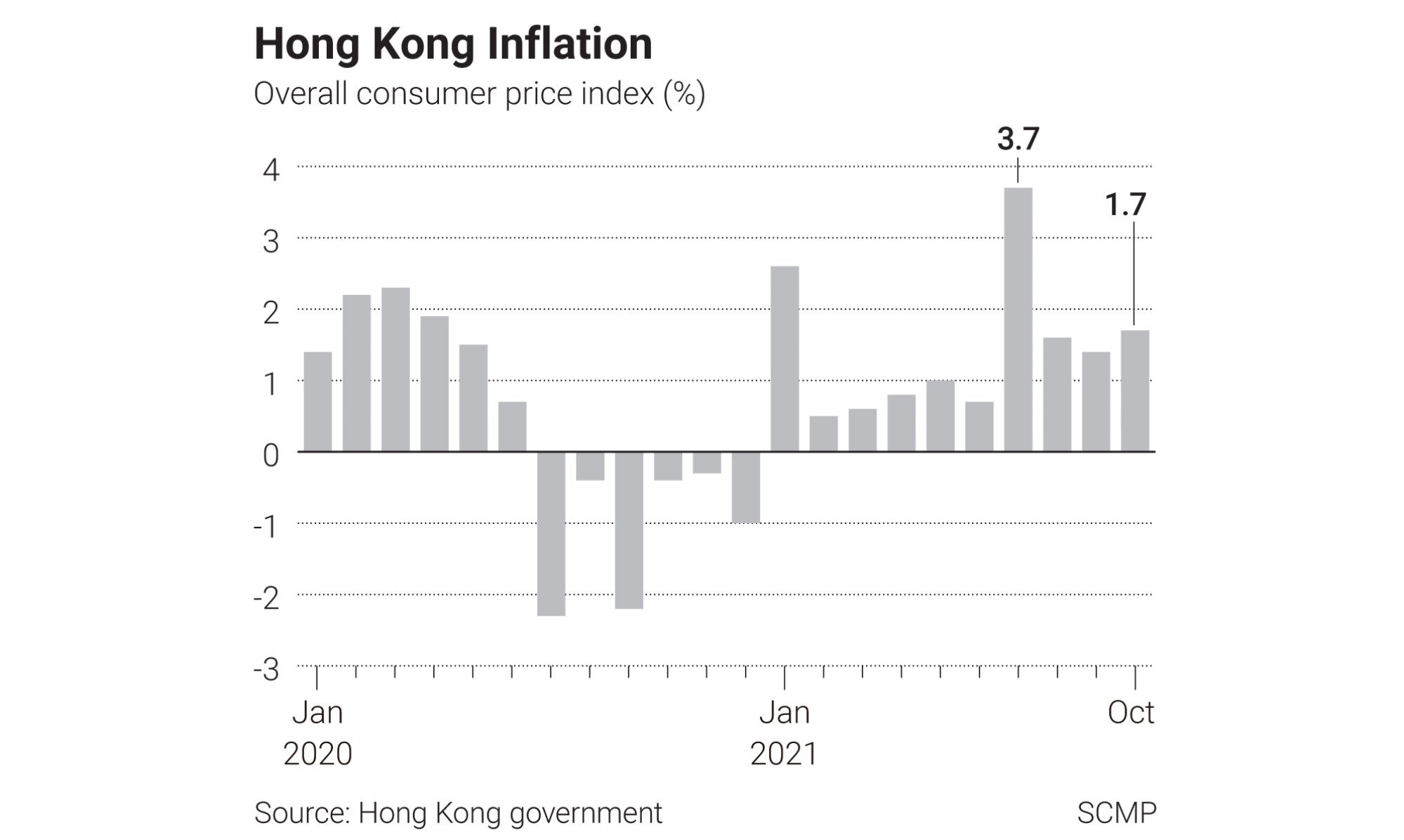

Yet, compared to many economies, inflationary pressure in Hong Kong is fairly benign. The overall consumer price index (CPI) in Hong Kong increased 1.8 per cent year on year in November, according to the Census and Statistics Department.

Even allowing for differences in calculation methods, the pace of consumer price increases in Hong Kong appears less pronounced than in those three economies.

Given that Hong Kong imports so much from mainland China, as long as policymakers in Beijing continue to keep a lid on upward price pressures there, the greater the likelihood that Hong Kong itself won’t import too much inflation from the mainland.

Inflation in Kazakhstan was already running at an annualised level of around 9 per cent even before energy prices soared at the start of January. The increase followed the decision, subsequently rescinded, to abolish a long-established cap on butane and propane prices.

But if Hong Kong’s inflation performance stands up well compared with mainland China, Britain, the US, and certainly Kazakhstan, there remains the wider risk that a stronger US dollar on foreign exchanges could result in US-dollar-denominated food and energy prices rising in local currency terms.

Whatever else happens with regard to broader US dollar appreciation on currency markets, the HKMA’s commitment to ensuring the Hong Kong dollar does not weaken beyond HK$7.85 to the US dollar remains firm, even though that resolve has been challenged by market speculators on occasion.

The bottom line is that Hong Kong now stands to benefit from Beijing’s self-interest in keeping inflation under control on the mainland. Meanwhile, the linked exchange rate will minimise the risk to Hong Kong’s economy of any emerging US dollar strength feeding through into higher local currency prices of US-dollar-denominated goods.

Like the rest of the world, Hong Kong will not avoid rising prices. Even so, the city looks better placed than many economies to be able to resist some of these inflationary pressures.

Neal Kimberley is a commentator on macroeconomics and financial markets