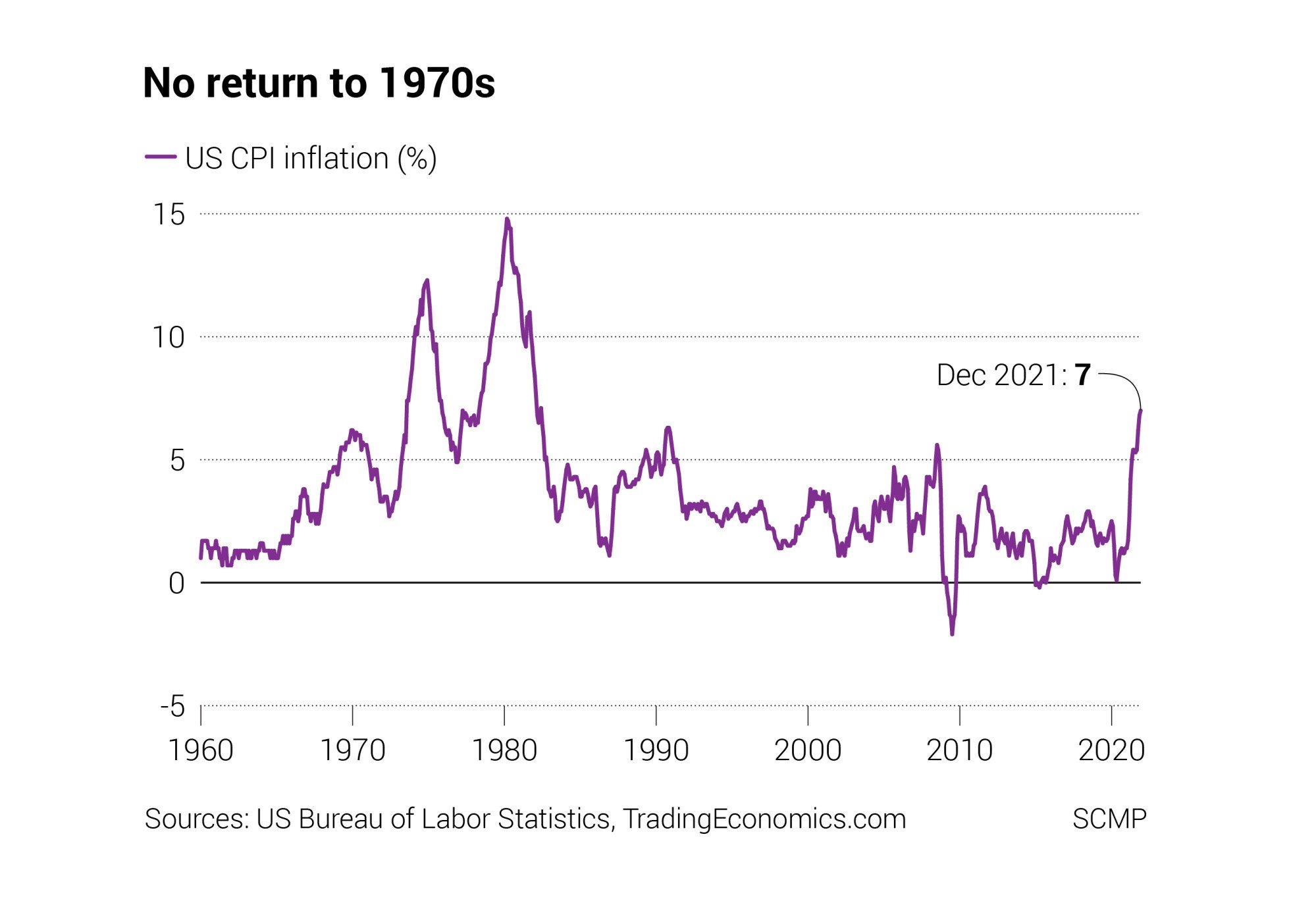

The US Federal Reserve can’t risk a return to the high inflation of the 1970s and 1980s

- Niggling fears over economic growth remain but with supply chain constraints still severe and energy prices that could spiral upwards under the threat of war in Ukraine, the Fed is right to raise interest rates as soon as possible

It is any central banker’s worst nightmare – wondering whether their monetary actions may have whipped up a storm of needless inflation risks. With global interest rates so low and the world economy on a robust recovery, it’s no wonder markets are so concerned that we may be heading back to the bad old days of high inflation seen in the 1970s and 1980s.

There is no easy answer to where interest rates should be right now. We may not be heading into a hyperinflation catastrophe, but the old hype about the end of inflation now looks wildly premature. Inflation is coming back, interest rates are heading higher and the world just has to get used to it.

In the Fed’s view, the odds are shifting towards inflation becoming more entrenched rather than transitory, especially with employment prospects bouncing back.

The US labour market seems in much better shape, with the headline unemployment rate at 3.9 per cent in December, closing in on its pre-pandemic cyclical low of 3.5 per cent in February 2020.

A more worrying development is that wage inflation pressures are heating up at the same time, with annual wages and salaries growth running at 8.8 per cent in November. Is the Phillips Curve, the inverse relationship between unemployment and wages, returning with a vengeance, especially as higher cost-of-living pressures begin to feed into demands for higher pay?

The Fed may be rightly obsessed with the deteriorating outlook for US inflation, but is there is a risk of hitting the panic button too soon? After all, there is an alternative view that suggests the world is not about to fall into a dangerous wage-price spiral raging out of control.

The International Monetary Fund offers a more positive outlook, suggesting that US inflation risks will peak in the first quarter of this year, eventually subsiding to the Fed’s consumer price inflation target of 2 per cent by 2023. There are still residual headwinds from the 2020 downturn dragging on growth, with spare operating capacity helping to contain price pressures.

Capacity utilisation levels in US industry are only running at 76.5 per cent in December, comfortably below peaks of above 80 per cent in earlier cycles.

The IMF’s belief that global inflation will peak this year probably presupposes that there will be some stabilisation in energy prices in the coming months.

Clearly, the impact of the post-pandemic supply-chain crisis and the energy price spike has thrown a curveball into earlier central bank notions about going easy on inflation to give global recovery a better chance.

That perceived passivity has been swiftly superseded. In the 1970s and 1980s, the transmission effect between higher energy prices and a vicious wage-price spiral was fast and furious, requiring an aggressive response from the global monetary authorities to contain the damage.

This time around, central banks can’t take any chances and the Fed is right to pull the trigger for higher rates as soon as possible. The age of monetary austerity has just begun.

David Brown is the chief executive of New View Economics