Advertisement

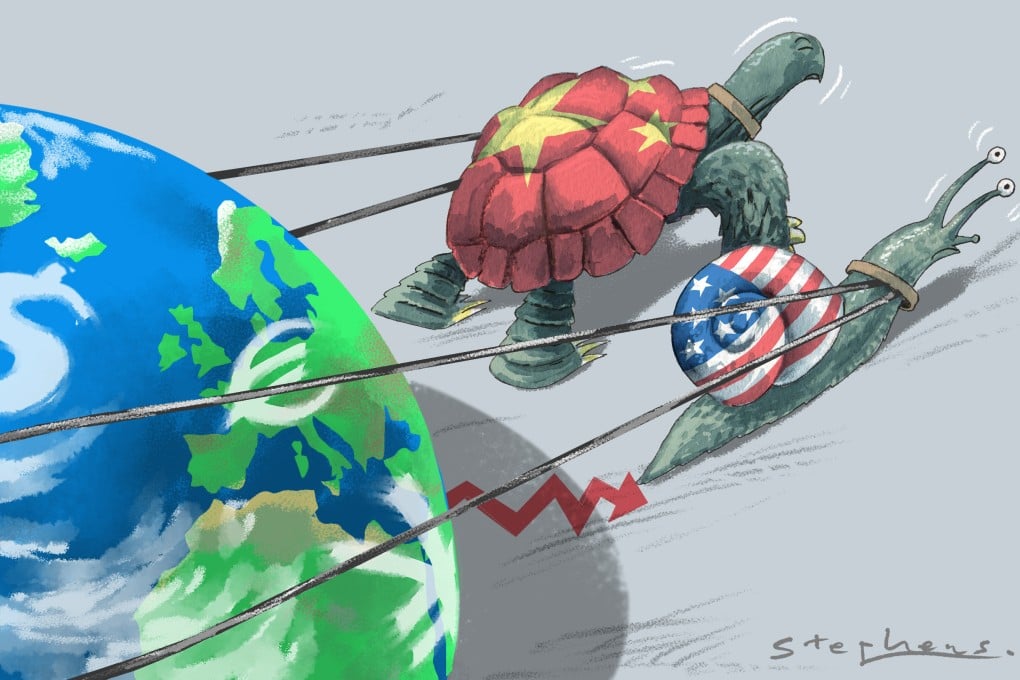

Opinion | How India and Southeast Asia can save global growth as US and China stagnate

- Both China and the United States, the two biggest engines of global economic activity, face severe slowdowns

- India and the ‘Asean-5’ could emerge as saviours of global growth, thanks to their young, tech-savvy populations and low wages

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

8

The global economy has had a pretty good run lately, with 5.5 per cent growth in 2021 after bouncing back from a brief recession two years ago. However, that growth is about to slow dramatically.

There is a Covid-19 pandemic that will not go away. Supply chains are snarled throughout the world. There is a potential military confrontation if Russia invades Ukraine. And now there is the threat of inflation, that insidious destroyer of wealth.

But where will growth come from when the United States and China – two engines of global economic activity for more than a decade – both face serious slowdowns? The US inflation rate is the highest it has been since 1982, when sweatbands were in vogue and Olivia Newton-John’s Physical topped the pop charts.

Advertisement

China’s inflation is on the rise as well and is set to reach a modest, though not insignificant, 1.8 per cent in 2022. Even at that level, it will eat away at dramatically slower growth this year. The International Monetary Fund estimates that the country’s economy will grow only 4.8 per cent in 2022, down roughly 60 per cent from last year’s 8.1 per cent figure.

Signs point to a third potential source of economic activity, however: India and the “Asean-5” of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. Collectively, they were the third-largest by GDP in 2020, and the IMF estimates they will be the fastest-growing economies for 2022 and 2023.

India is on track to displace the UK as the fifth-largest economy in the world. With GDP expected to grow at 9 per cent this year and with one of the largest populations in the world, the continental giant could also become a major regional hub of economic activity.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x