Inside Out | Pandemic reminds us how far humans have come in war against infectious disease – and far we still have to go

- Scientific progress has given us more knowledge of – and control over – pathogens than at any other time

- Human expansion has also created an environment in which viruses and bacteria thrive, while a lack of collective responsibility leaves those most vulnerable with the least protection

Inevitably, he answers cryptically: it is too early to know. But for those who feel confident that the plagues and pestilences of past centuries are safely behind us, Harper’s new book, Plagues upon the Earth, provides a sobering call for caution. “Coronavirus did not appear out of the blue. It stands in a continuous line of emerging threats, and it follows an unbroken series of near misses,” he warns.

While not making light of the remarkable progress we have made in containing the pestilences that have through 200,000-300,000 years of human history regularly culled populations, Harper warns that “humanity’s control over nature is necessarily incomplete and unstable … We do not, and cannot, live in a state of permanent victory over our germs.”

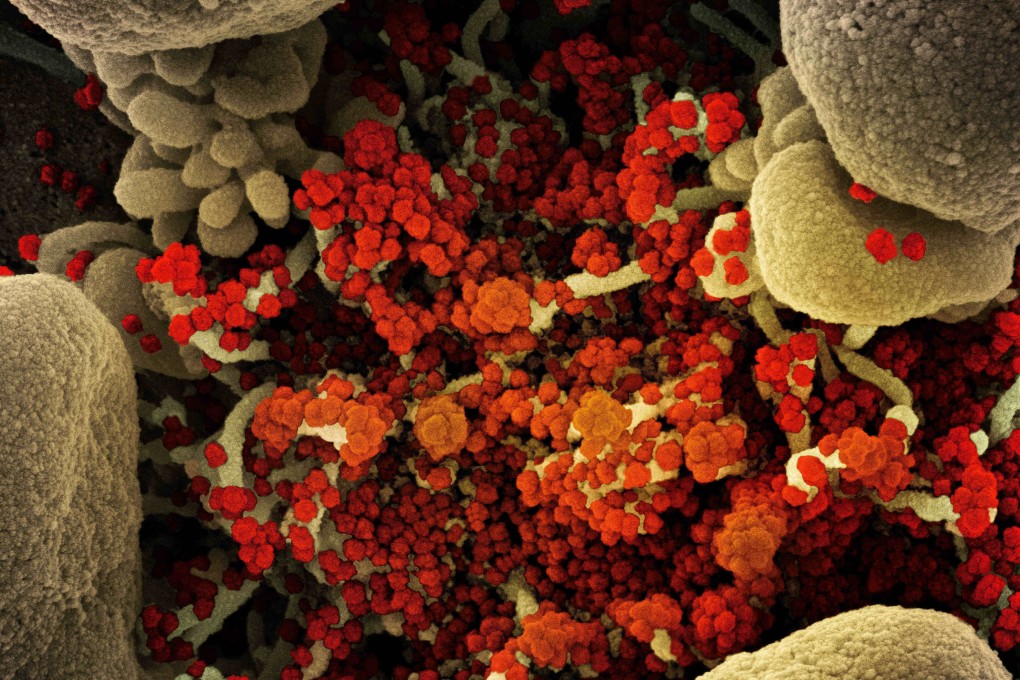

But, at the same time, human progress has created an environment where our microbial enemies can thrive: “Our exposure to the threat of new diseases has never been greater, simply because of our numbers,” says Harper. In short, humans have become an irresistible target for an unparalleled range of bacteria and viruses that depend uniquely on us and on the disequilibrium we have created in the “Anthropocene Age”.

“What we think of as a medical triumph – the control of infectious disease – is from a planetary perspective a truly novel, systemic breakdown of an ecological buffer,” says Harper, marvelling at the “dizzying novelty of the current experiment in human supremacy”.