Advertisement

Inside Out | Climate change action can’t wait for Ukraine war and pandemic to pass

- The latest IPCC report on the increasing severity of climate change appears to have come and gone with barely any mention

- While the war in Ukraine, the pandemic and local politics might hold our attention, the need for meaningful action on climate change grows greater

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

7

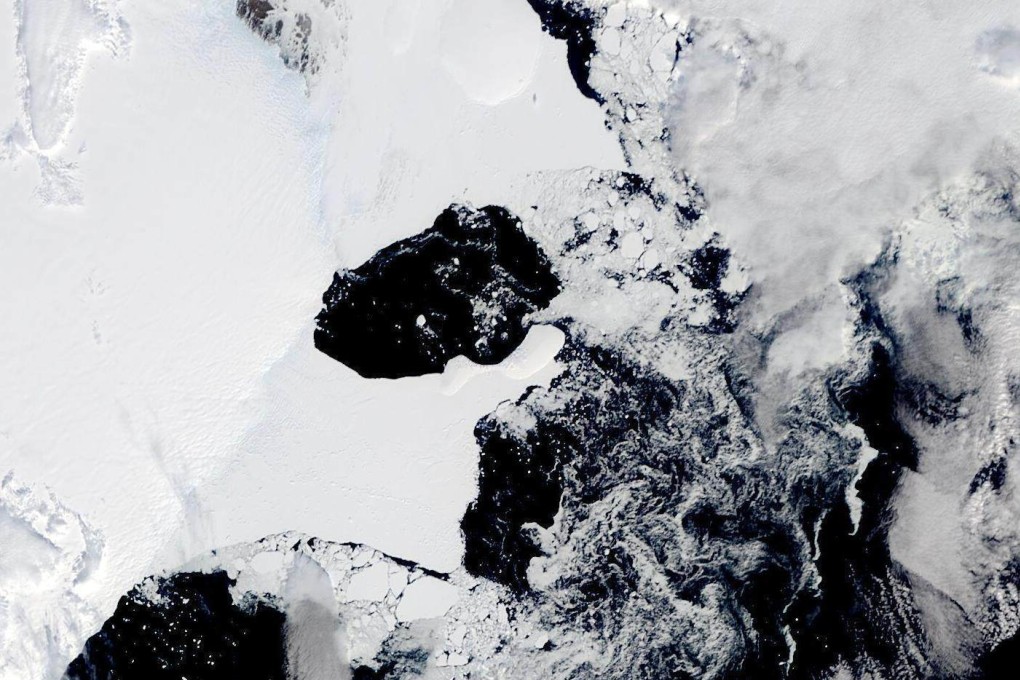

On March 15, the 1,200 sq km Conger ice shelf in Antarctica collapsed. Three days later, the Concordia research station in Antarctica recorded a temperature of minus 12 degrees Celsius, a stunning 40 degrees above seasonal norm. Out of sight and out of mind, global warming continues apace whether we care to notice or not.

Meanwhile, London-based writer James Bridle is trying to get us to focus on “the present average velocity of climate change” – the pace at which plants and animals are migrating in response to changing weather. In the United States, “the conifers are mostly heading north, while broad-leafed and flowering trees, such as oaks and birches, move west”. White spruce moving northwards do as at a pace of more than 100km each decade.

While humans bluster and procrastinate, our trees, plants, birds, butterflies and mosquitos are getting on with the painful but essential process of adjustment.

Advertisement

Like me, Bridle must be pained to see the latest 3,000-page report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) go virtually unnoticed last week, despite its warnings about the imminent and dire consequences of global warming. It seems our natural world is taking more notice than we are, even without the benefit of armies of climate scientists and huge IPCC reports.

It is not just the dull prose of the report’s authors that is to blame. Neither can our political leaders and our media be wholly blamed for being more concerned by the issues of the day – whether that means the Covid-19 pandemic, Russia’s war on Ukraine, the emergence of John Lee Ka-chiu as Hong Kong’s likely next chief executive or the “tax management” antics of Akshata Murthy, millionaire wife of British finance minister Rishi Sunak.

Advertisement

But the scary reality is that we continue to turn a blind eye. In the frenzy of climate debate focused on the UN climate summit in Glasgow last November, the world was awash with pious promises and unanchored commitments to “net zero”. This latest report is similarly full of scientific counsel on how to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x