Macroscope | Why the US Federal Reserve can’t kick the inflation can down the road much longer

- While the 10-minus-two-year Treasury spread seems to be an early precursor to possible recession, the front end of the US curve seems to carry a different message, that the Fed is still holding back and lagging behind what’s needed to tame inflation

Years of near zero interest rates and the Fed’s quantitative easing programme, which has exploded the central bank’s balance sheet close to US$9 trillion, have made great progress. The measures have staved off deeper disaster from the 2008 crash and supported the economy while the Covid-19 pandemic raged. But with headline consumer price inflation running at 7.9 per cent and due to go higher in the coming months, super-stimulus has overstayed its welcome.

Hints of impending half-point interest rate hikes seem to have impressed so far but is the Fed leaving the job half-finished and the markets short-changed?

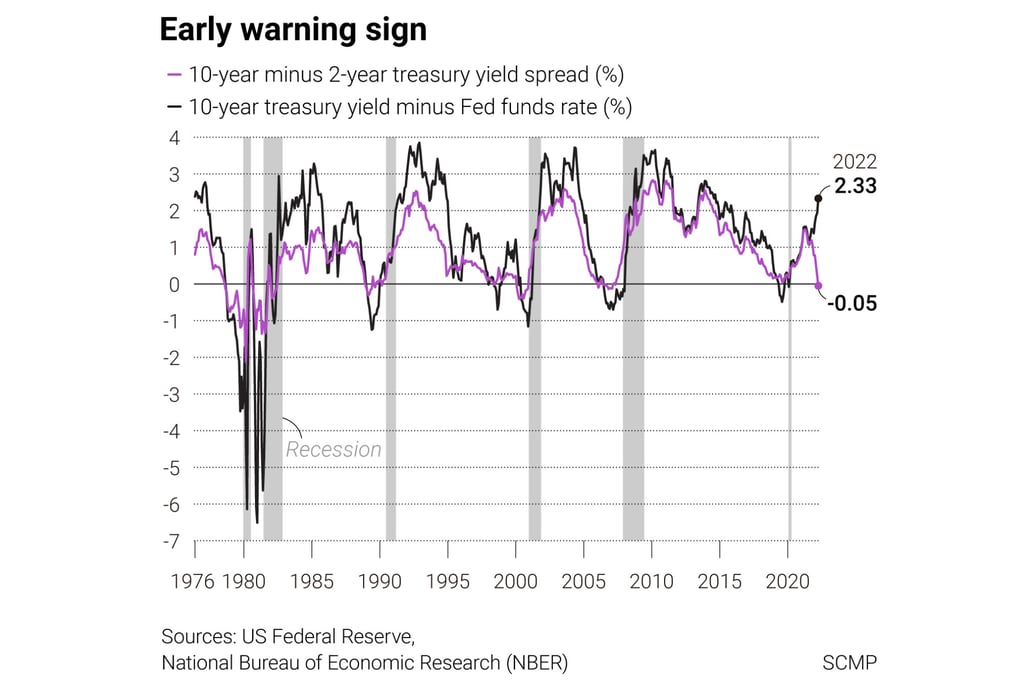

It seems to be what the spread between the two- and 10-year Treasury bond yields is hinting at, having dipped back into negative territory in recent trading sessions. Since the 1970s, inversion of the 10-year less two-year Treasury spread has strongly correlated with foreshadowing the US economy falling into recession by anywhere between six months and two years further ahead. Should we be worried the Fed is about to risk a new recession with a tougher policy onslaught?

It really depends which part of the US yield-curve you look at. While the 10-minus-two-year Treasury spread seems to be an early precursor to possible recession, the front end of the US curve seems to carry a different message – that the Fed is still holding back and lagging behind what’s needed to tame inflation.