Macroscope | Central banks are doing more harm than good as they seek to control inflation

- Raising interest rates to control inflation is too blunt a weapon to aim at the fragile global economy, and risks triggering another recession

- Central bank policy needs to embrace the bigger issues of social deprivation and welfare needs

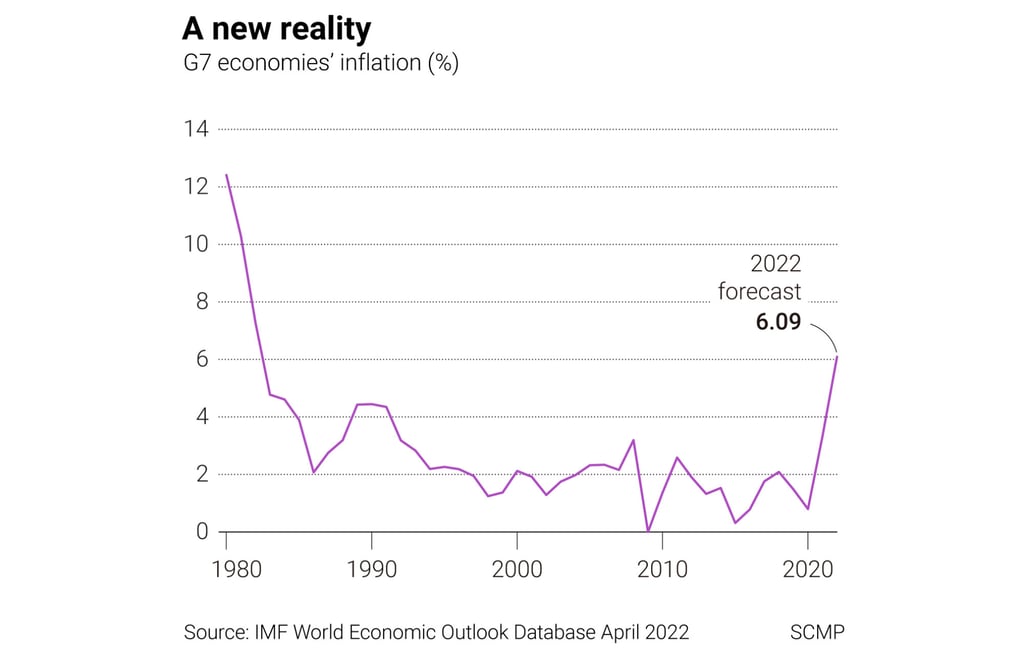

Central banks are moving towards tougher interest rate tightening, but at what cost? They are on a quest to rid the world of higher inflation, but are they driving the global economy into needless recession in the process?

They may be our chosen champions against spiralling inflation, but central banks’ job is not to achieve price stability at any cost, not least another recession so soon after the 2020 Covid-19 downturn and while the Ukraine conflict threatens even more turmoil.

If global policymakers learned one key lesson from the 2008 financial crash, it might have been that the rush into fiscal tightening before the world had time to recover fully caused needless damage to global recovery.

The legacy of sub-par economic growth and heavy structural unemployment left the world overexposed to the Covid-19 pandemic and its aftermath in terms of output volatility, supply-chain shortages and rising inflation risks. The Ukraine conflict couldn’t have come at a worse time for policymakers, struggling to cool demand and contain the risks to inflation from interest rates which remain far too low.

The challenge now is finding a middle road which keeps global recovery on track while keeping a lid on inflation, without causing any more damage along the way.