Opinion | How rising India’s Quad role is helping it find its place among global powers

- New Delhi is moving quickly to take on more multipolar responsibilities as it grows into a diplomatic and economic force within Asia and beyond

- This shift from a neutral position is largely due to China’s growing influence, with relations plagued by mistrust over armed conflict along their shared borders

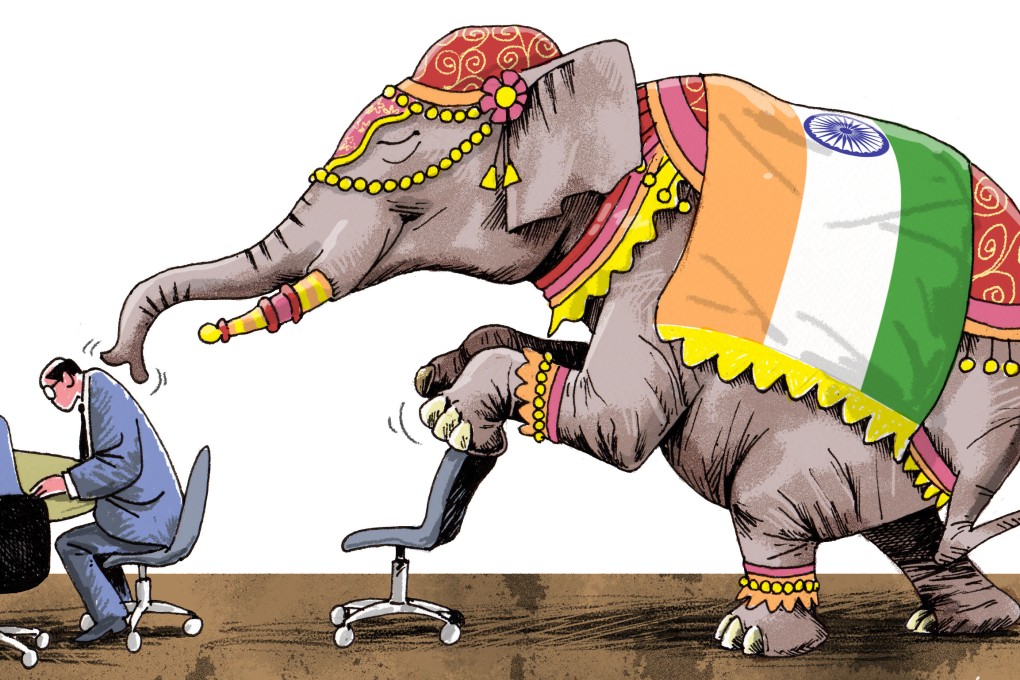

India is on a diplomatic roll. New Delhi has been signing agreements left and right with a host of major international partners in what appears to be Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s calculated attempt to secure a place among global power brokers. By all accounts, it’s working.

Their joint statement read in part, “The Quad is committed to cooperation with partners in the region who share the vision of a free and open Indo-Pacific.” This means not only support for the international rules-based system, including the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, but more specifically the East and South China seas.

Such a far-reaching declaration marks a significant departure from India’s non-aligned positioning during the Cold War. New Delhi deftly managed to court both the US and the Soviet Union at the time as the two superpowers battled for spheres of influence.

In the 2021 financial year, even with the limiting effects of the Covid-19 outbreak, the US granted more than 250,000 non-immigrant visas to Indian nationals. That is more than double the number granted to Chinese.