Macroscope | Federal Reserve’s quantitative tightening plan is a welcome dose of predictability

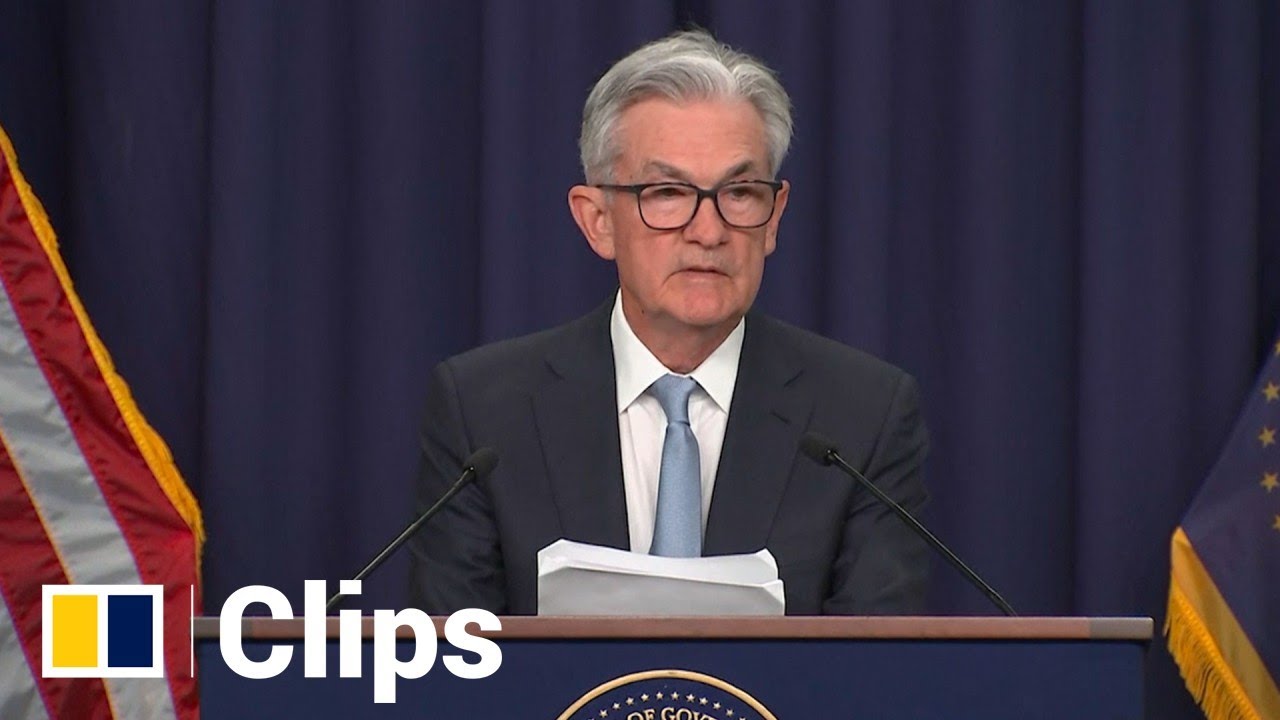

- While the shift from quantitative easing to tightening has happened very quietly, the path for running down the balance sheet was well telegraphed by the US central bank

- This is in sharp contrast to the rhetoric from several Fed officials on interest rates

The US equity market fell further into bear-market territory – down more than 20 per cent from its high in early January – and yields on government bonds rose. However, what is striking about all of the discussions around the market and economic outlook for the United States of late is what is not being said, specifically quantitative tightening.

With central banks, particularly the Fed, preoccupied with the size and number of interest rate increases, it’s starting to become evident that the shift from quantitative easing to quantitative tightening has happened very quietly in the background.

Earlier this month, the Fed took the first step in its balance sheet unwinding by allowing billions in US Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities to mature and roll off the balance sheet without being replaced. The path for running down the balance sheet was well telegraphed by the Fed and had a clear structure.