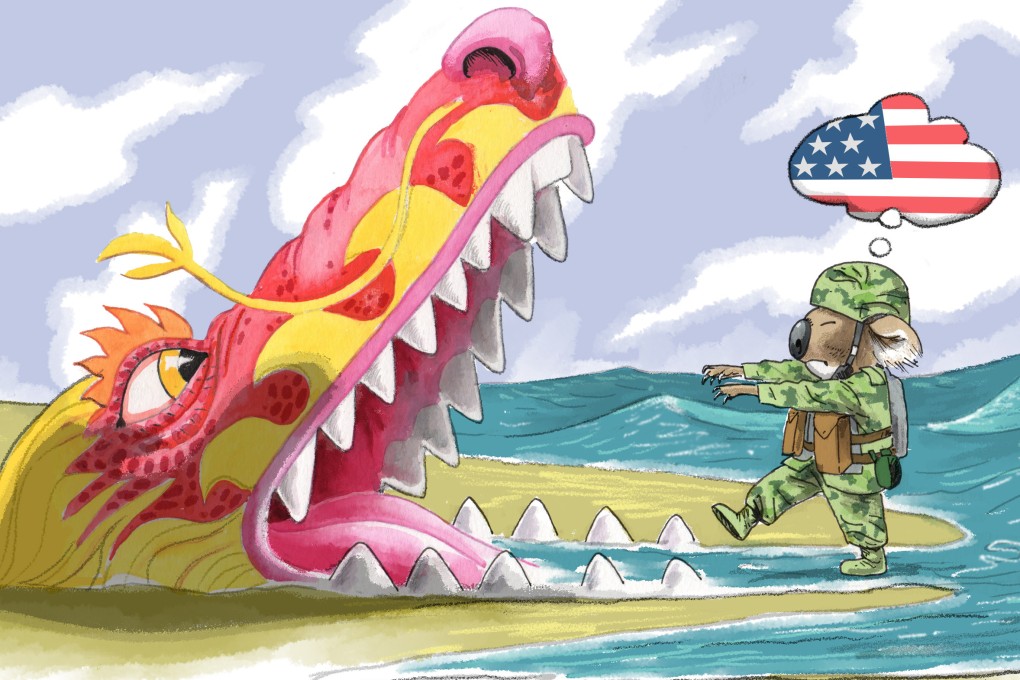

Opinion | Australia is risking its own neck for the US in the South China Sea – has it stopped to ask why?

- Canberra echoes Washington’s arguments about freedom of navigation and mimics US surveillance activities in the South China Sea, while claiming it acts in its own interests

- Yet it must ask itself: how does provoking a possible military conflict serve the country or region?

Indeed, as the US-China struggle for domination in the South China Sea becomes ever more dangerous, Australia finds itself at the edge of an intensifying political and military whirlpool. Australia needs to re-evaluate its interests and policies lest it be unwittingly sucked in.

On June 5, the Australian Defence Department stated that, 10 days earlier on May 26, “a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) P-8A maritime surveillance aircraft was intercepted by a Chinese J-16 fighter aircraft during a routine maritime surveillance activity in international airspace in the South China Sea region”.

Australian Defence Minister Richard Marles said the Chinese aircraft flew very close to the P-8A, released flares, then cut across its nose and released a “bundle of chaff” that was ingested by the P-8A’s engines. Australia said this was “dangerous” and “threatened the safety of the aircraft and crew”.

China’s Defence Ministry responded that “the Australian military aircraft seriously threatened China’s sovereignty and security and the countermeasures taken by the Chinese military were reasonable and lawful”.