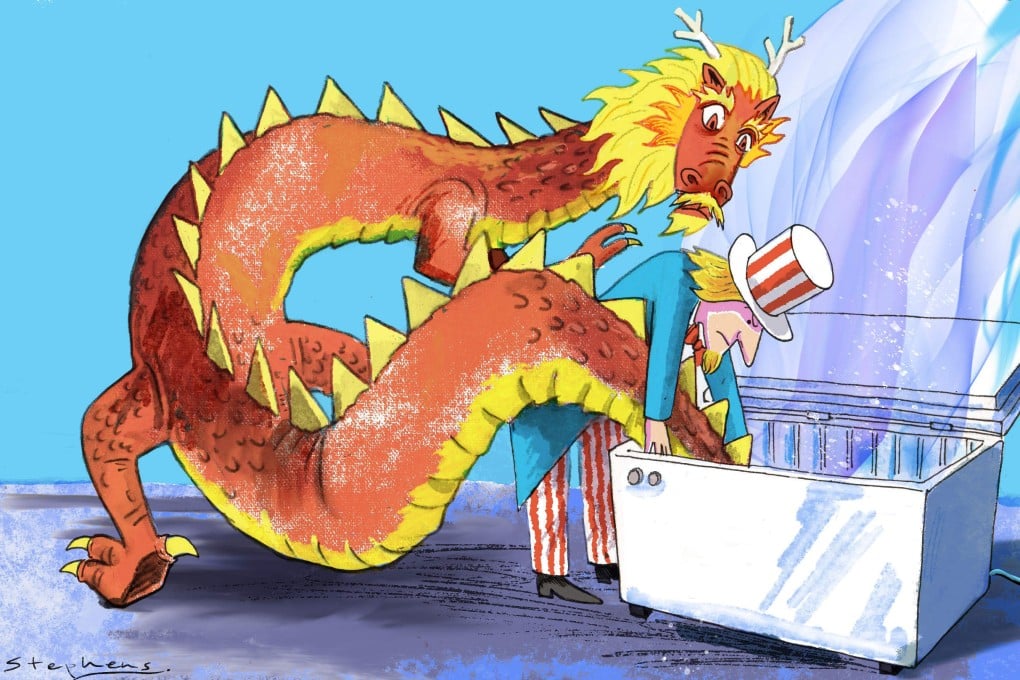

Opinion | Why the US using a Cold War ‘containment’ strategy against China would be a colossal error

- The containment strategy was unveiled 75 years ago, during the ideological conflict between Western capitalism and Soviet socialism

- This strategy simply wouldn’t be effective against ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’ and a Chinese economy that will outstrip that of the US

Seventy-five years ago this month, American diplomat George Kennan published an influential essay in Foreign Affairs in which he unveiled the idea of “containment” for the first time. In “The Sources of Soviet Conduct”, he advocated applying this strategy to Soviet expansionism at a time when Moscow was encroaching on the interests of a stable world order.

The essay struck a chord with the Euro-Atlantic world, which was grappling with the Kremlin’s intransigent ways in the aftermath of World War II. Containment became the West’s geopolitical doctrine in the Cold War era.

In Kennan’s telling, the dictatorship in Moscow viewed the capitalist system of production as nefarious and exploitative. No “community of aims” could be had between socialism and capitalism. The overthrow of capitalism, no less, by a rival centre of ideological authority and geopolitical power was the goal.

Moscow grasped that patience would be required for it to prevail globally, given that it could not match up against the capitalist powers yet. Like the church, the Kremlin was “under no ideological compulsion to accomplish its purposes in a hurry”, as Kennan put it. The compulsion, rather, was for revolutionary socialist forces worldwide to be unswervingly loyal to the Kremlin’s infallible doctrinal and strategic leadership in the fight against capitalism and the West.