Advertisement

Macroscope | The biggest loser of the energy crisis? Global economic recovery

- With no resolution of the war in Ukraine or the energy crisis in sight, global financial stability will come under mounting pressure

- Global policymakers must provide much more multilateral support to struggling nations as the world cannot afford another financial shock

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

There will be winners and losers from the global energy crisis, but it’s a less than zero-sum game for the world economy as it slides towards possible recession in the next year.

Oil producers are reaping bumper revenues from the spike in global oil and gas prices, but it’s the net-energy-consuming countries that represent the bulk of the world economy that pose the greatest risk to recovery prospects as higher inflation takes its toll on global confidence. With the US dollar on a roll from rampant safe-haven demand and dollar-based energy costs soaring, there is severe strain on global trade imbalances, increasing the chances of a major sovereign debt default.

With no short-term resolution of the Ukraine crisis in sight, global financial stability will come under mounting pressure. It calls into question the central banks’ sudden shift to tighter monetary policy, forcing governments to keep fiscal stimulus in overdrive for much longer than anticipated.

Advertisement

The surge in global energy prices and the threat of disruption to oil and gas supplies is affecting business sentiment across all the major economies. From Europe to the United States and China, it is raising production costs, squeezing profit margins, sucking money out of consumers’ pockets and denting demand in the process.

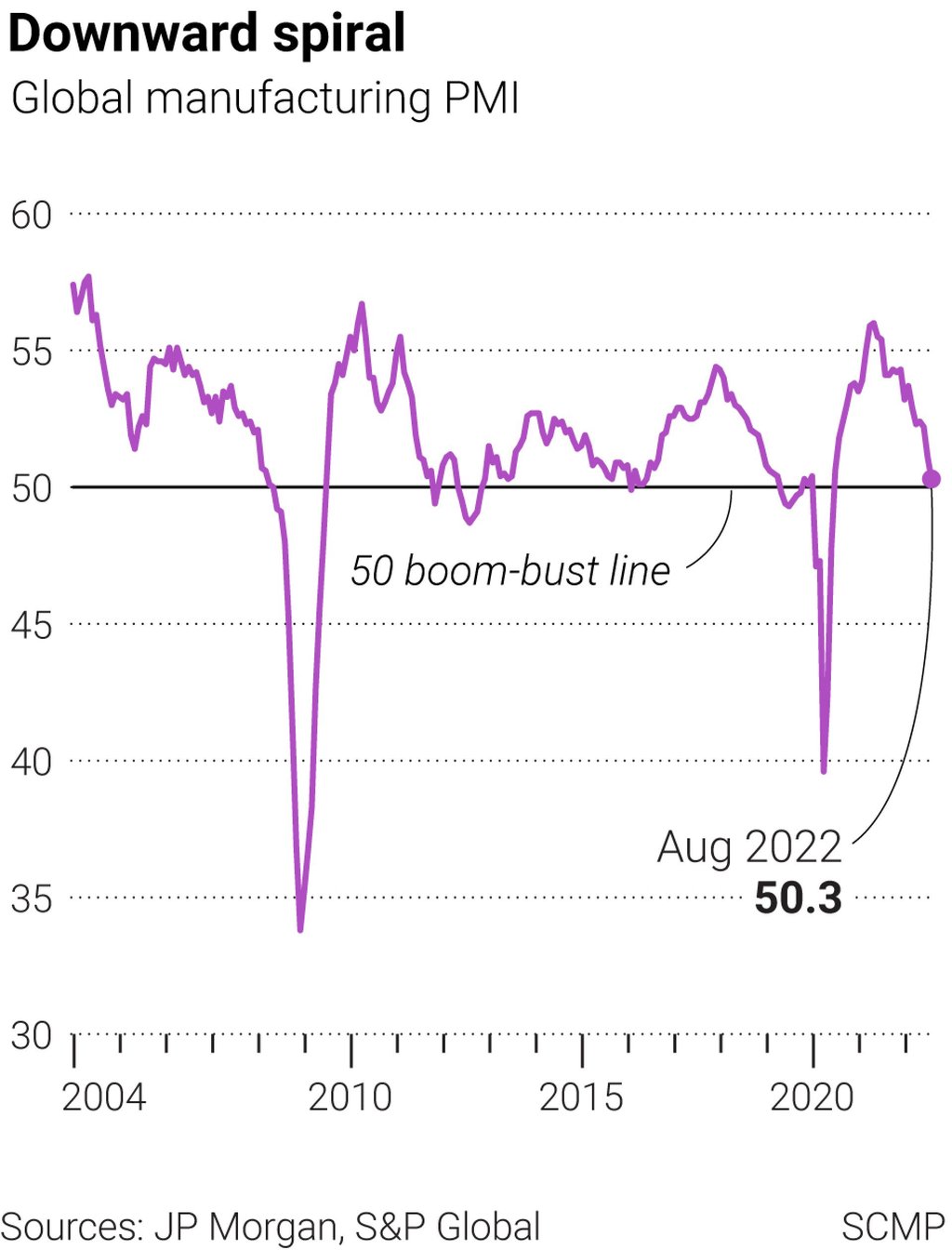

The global economy is heading into a downward spiral of negative gloom, made even worse by serious drought conditions around the world. The threat of major power outages and growing food shortages as the cold winter months draw near is adding extra burdens to a global economy which is struggling to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic.

The major forecasting bodies seem behind the curve on spelling out how bad it might get over the future. The latest forecasts from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank seem in a reasonable consensus that global growth will slow down from 5.7 per cent in 2021 to around 3 per cent for 2022 and 2023.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x