Advertisement

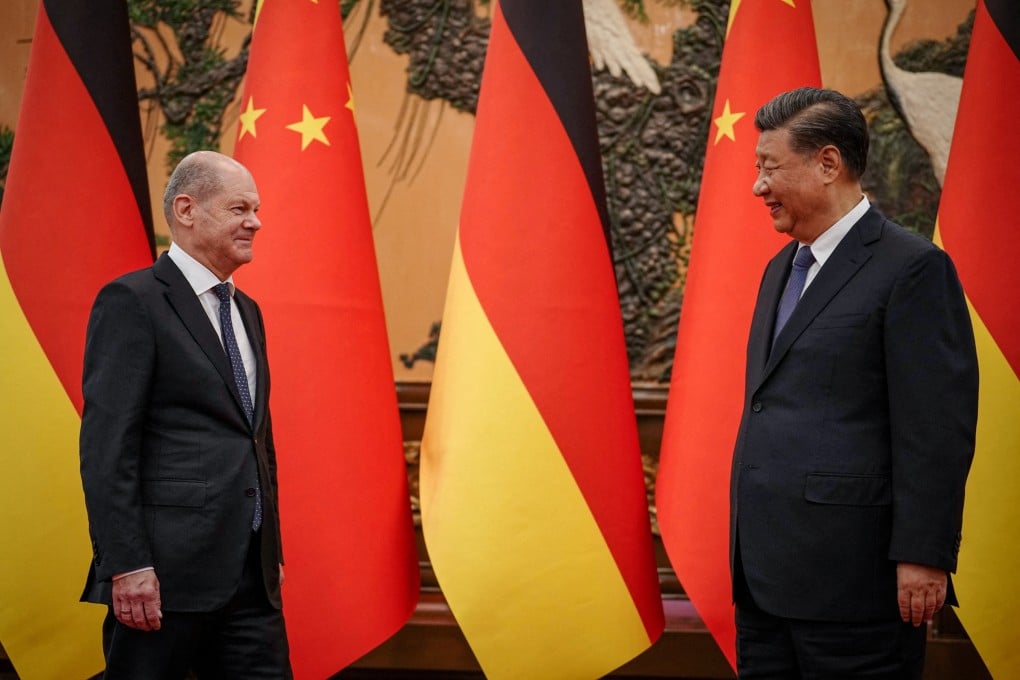

Opinion | Scholz’s Beijing visit brings hope for EU-China relations

- The German chancellor’s short visit with a business delegation has broken important ground when Germany, like the rest of Europe, faces the very real risk of recession

- German firms’ commitment to China suggests that, despite the talk of decoupling, the real momentum is towards more engagement with China

3-MIN READ3-MIN

1

Contrary to the narrative of decoupling that is gaining traction in the West, Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s flying visit to Beijing last week, with 12 CEOs in tow, is proof that Germany still puts business first when it comes to China.

Looking at the economic context, it isn’t hard to see why. Germany derives half its gross domestic product from exports and China has been its top trading partner for six years on the trot. Commerce with China supports over a million German jobs directly, and millions more indirectly.

The depth of ties between the two economies is even more apparent when looking at the balance sheets of individual companies. China accounts for over 30 per cent of global sales of carmakers like Volkswagen, Daimler and BMW – and over a fifth for other DAX heavyweights such as Covestro and Adidas. Infineon, the German chip maker, derives a whopping 37.9 per cent of its sales from China.

Advertisement

These economic links are crucial when Germany, like the rest of Europe, faces a deepening energy crisis, high inflation and the very real risk of recession.

Berlin can hardly afford to aggravate its current economic predicament by supporting an economic decoupling of the European Union from China – a move that could cost Germany almost six times as much as Brexit, according to the Munich-based ifo Institute, or €48.4 billion (US$48.5 billion) in real income, according to the Kiel Institute for the World Economy.

Advertisement

Despite the current economic challenges, the war in Ukraine has led to more calls for Scholz to curtail commercial ties with China, including from within his own coalition.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x