Advertisement

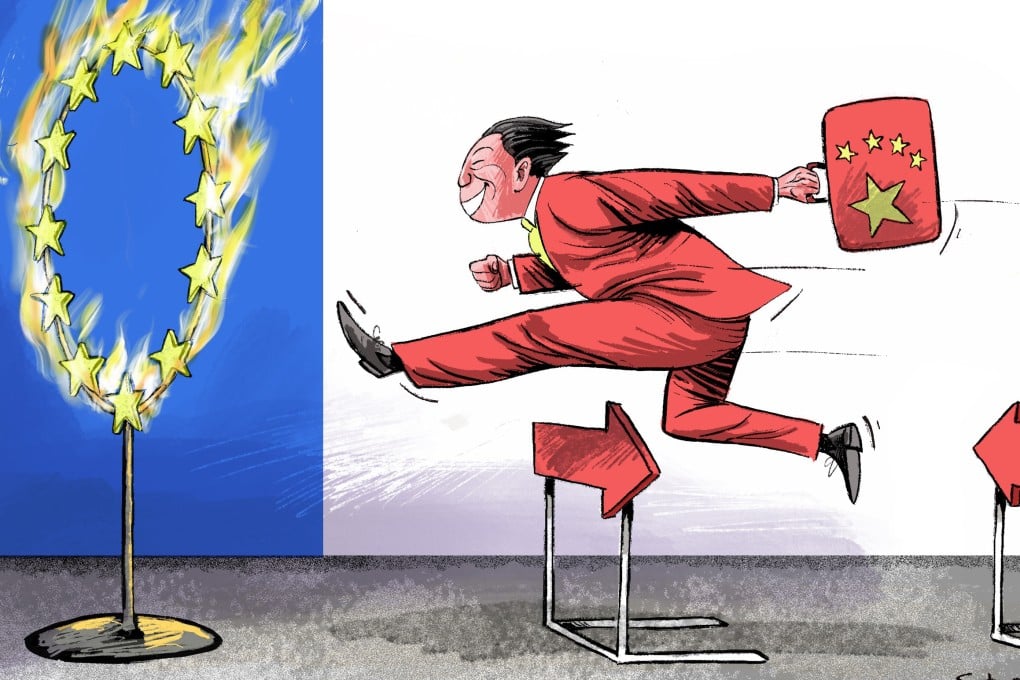

Opinion | China’s European charm offensive faces hurdles of domestic politics, trade issues

- China is starting its latest effort to drive a wedge between the US and Europe, but it is unlikely to change fundamental differences that impede warmer ties

- Europe wants greater access to China’s markets, but domestic political concerns could keep European leaders from appearing too friendly with Beijing

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

1

The trip to Europe in April by China’s trade emissary is the latest in a frenzy of overtures by high-level Chinese officials to drive a wedge between the United States and European Union while leveraging divisions within Europe over an engagement strategy – “de-risk” but not “decouple” – with China that promotes economic growth as recession looms.

Commerce Minister Wang Wentao will follow the week-long tour in February by China’s top diplomat, Wang Yi, whose major speech then was an attempt to deepen the Washington-Brussels divide developing over semiconductor trade and investment policies. Wang called Europeans “friends” while mocking Washington’s “hysterical” reaction to Chinese balloons over US airspace.

Less US influence over its allies would be a geopolitical victory in China’s eyes. Towards this end, China’s new ambassador to the European Union, Fu Cong, has been actively courting European governments since his appointment in December. Low-profile discussions are also under way on numerous issues.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, Europe’s leaders have been busy shuttling to China. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz reopened high-level exchanges with China by visiting Beijing in November to meet President Xi Jinping. Before his trip, Scholz cleared a Chinese shipping company’s stake in Germany’s busiest port at Hamburg.

Berlin cannot afford to cut ties with its third-largest export market. China has also been a back-door supplier of gas to Europe since Russia sharply cut supplies, and Germany was heavily dependent on the Nord Stream pipeline.

Advertisement

Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, is travelling to China this week with French President Emmanuel Macron. Her speech before departing was scathing in suggesting that the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment – which was agreed in 2020 but has stalled in the European Parliament – could implode.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x