Why the party isn’t over for the US dollar just yet

- Amid another wave of dollar hatred, BRICS nations are talking up a common currency, while the yuan’s share of global trade finance has tripled in recent years

- Yet, ‘King Dollar’ plays a unique role in the global economy and also has luck on its side

Every so often, de-dollarisation emerges as a popular narrative in financial markets. In the years leading up to the 2008 financial crash, the dollar index – a gauge of the US currency’s performance against its main peers – was dropping fast, partly because of optimism around emerging markets but also because of concerns about America’s widening current account deficit. This precipitated what Jens Nordvig, founder of macroeconomic research firm Exante Data, calls a wave of “dollar hatred”.

While the greenback eventually stabilised – largely because of its status as a safe haven that benefits from periods of turmoil – a resurgence of dollar hostility took hold in 2009-10 when many developing economies blamed the Federal Reserve’s ultra-loose monetary policies for drawing too much capital towards higher-yielding emerging markets. This caused developing nations’ currencies to appreciate rapidly, fuelling talk of “currency wars”.

Fears and resentment of the dominance of the dollar, coupled with the US government’s own admission that Western sanctions could undermine the greenback’s hegemony, have increased the appeal of alternatives to dollar-denominated financing and trade.

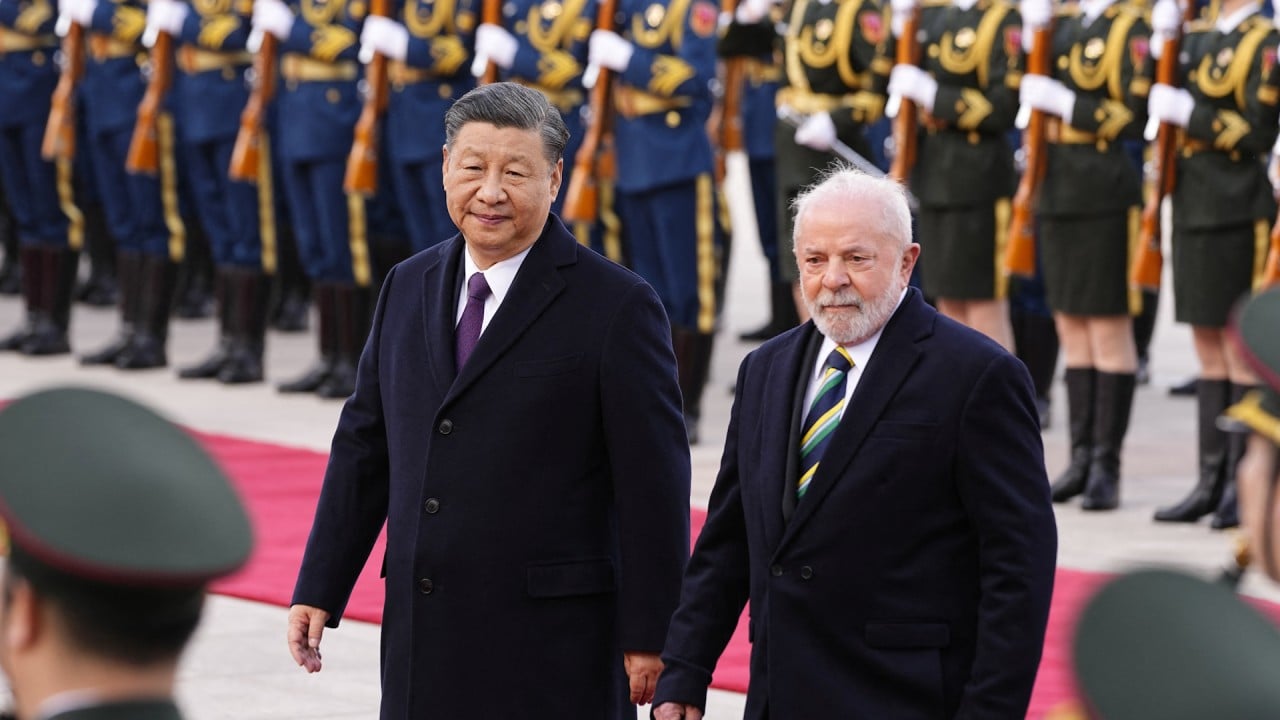

Last week, foreign ministers of the BRICS group of countries asked the New Development Bank – the Shanghai-based lender launched in 2015 as a counterweight to Western multilateral institutions – to provide guidance on how a potential new common currency might work.

Yet, every upsurge of dollar hatred collides with the harsh reality of the greenback’s primacy and, just as importantly, the lack of a viable alternative to supplant it as the dominant reserve currency. While a more multipolar and less-stable world poses bigger challenges to the dollar, the powerful forces underpinning its hold on the global economy endure.

The BRICS bloc, on the other hand, features a much more diverse group of countries. China is the world’s second-largest economy, Russia is a sanctioned pariah, South Africa and Brazil have struggled to grow, while India is competing fiercely with China for geoeconomic influence. Any attempt to create a shared currency would be like herding cats.

Second, there is a reason the US currency is dubbed King Dollar. It is involved in 88 per cent of foreign exchange transactions, compared with 31 per cent for the euro and 17 per cent for the yen, data from the Bank of International Settlements shows. The dollar also accounts for about 60 per cent of official foreign exchange reserves, while around half of global trade is invoiced in dollars.

Several key attributes make the dollar’s role in the global economy unique. They include the sheer size of the US economy and the freely convertible nature of the greenback. Crucially, the dollar benefits from huge network effects: switching from a currency everyone else uses is inconvenient and difficult.

Third, the greenback has what Nordvig calls “that special ‘magic’.” The dollar benefits hugely from its “exorbitant privilege” which allows the US to fund its large fiscal deficits while keeping interest rates lower and asset prices higher than they might otherwise be. It also means the dollar gains in times of crisis, even if the crisis originates in the US itself.

However, constraints on the yuan’s internationalisation are significant due to China’s unwillingness to relinquish control over its capital account and financial system. The yuan’s share of global payments made on Swift, the international payments system, has stood at 2 per cent for several years.

The dollar also has luck on its side. Many investors thought the greenback would decline this year as US interest rates peaked. Yet, the Fed keeps raising rates while the economy continues to dodge a recession, triggering a rally in the dollar.

Nicholas Spiro is a partner at Lauressa Advisory