Advertisement

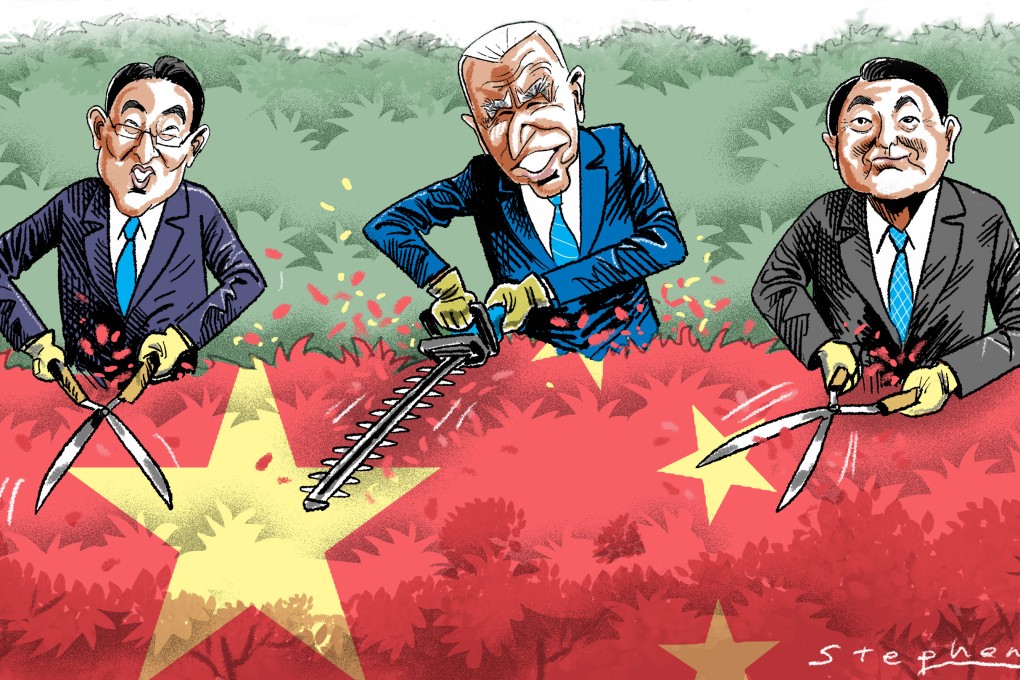

Opinion | Deepening cooperation between US, Japan and South Korea provides economic and strategic hedge against China

- The recent Camp David summit is the result of efforts by Tokyo and Seoul to take coordinated action on shared security concerns over China and North Korea

- The trilateral interaction with the US is Japan and South Korea’s geopolitical insurance against the risks associated with a more dominant China

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

7

The announcement last week by leaders of the United States, Japan and South Korea of a mechanism for trilateral consultation and coordination – in response to threats to any of their countries “from whatever source” – seems to be the embryo of a “mini-Nato” in East Asia. This move means China will not sleep peacefully.

Beijing sees the deepening of Japanese-South Korean ties as part of the US strategy to contain its rise through a vast network of alliances and partnerships. Consider, for example, the effect of a combination of US, Japanese and South Korean naval and missile forces conducting exercises near the entrance to the Yellow Sea and Bohai Gulf, the gateway to the Beijing-Dalian-Qingdao triangle, which forms the geographical core of China’s political and military power.

The Camp David summit between US President Joe Biden, South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida was the result of renewed efforts by Tokyo and Seoul to try to set aside their historical disputes in the face of shared security concerns over China’s geopolitical assertiveness and North Korea’s growing nuclear and missile capabilities.

Advertisement

Pushed by the US, Japan and South Korea probably have a window of four years to cement their rapprochement. The time frame coincides with the remaining period in office for Yoon, who is risking his political capital at home to mend ties with Tokyo after relations deteriorated under his predecessor Moon Jae-in.

Japan and South Korea have long had tense interactions because of the Japanese colonial occupation of the Korean peninsula. Tensions skyrocketed after Moon rejected a 2015 arrangement on the “comfort women” issue.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x