Advertisement

Advertisement

Opinion

Macroscope

by Nicholas Spiro

Macroscope

by Nicholas Spiro

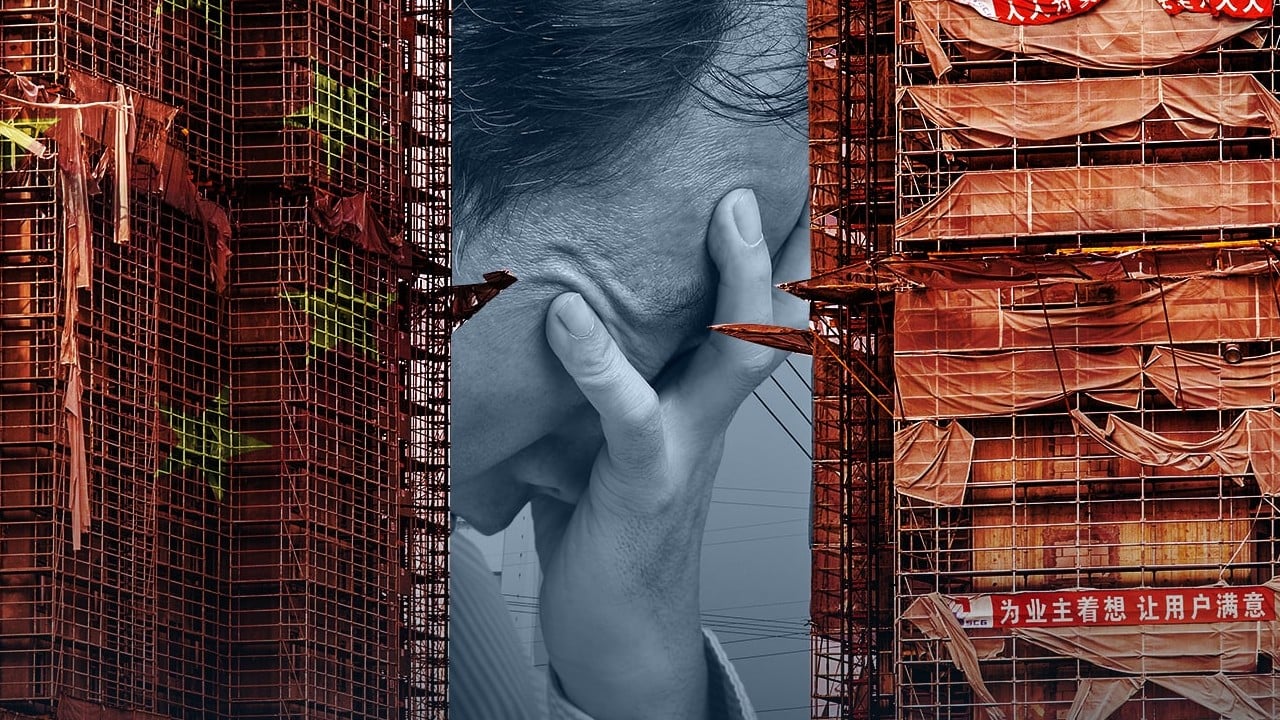

How can China hit its GDP target when it needs to grow just to stand still?

- Li Qiang admitting Beijing will have a hard time delivering on its pledge of 5 per cent GDP growth is an understatement, given China’s economic struggles

- The government’s policy response has been piecemeal, equivocal and confusing, frustrating investors and sapping confidence among domestic consumers

Does anyone really believe that China will hit its growth target for this year of “around 5 per cent”? Even Premier Li Qiang, who announced the ambitious goal on Tuesday at the opening session of the annual National People’s Congress, is sceptical, acknowledging that it will not be easy for Beijing to deliver on its pledge.

This is an understatement. For starters, last year’s economic performance was flattered by a low base effect stemming from citywide lockdowns during the Covid-19 pandemic. Moreover, the tailwinds in the first half of 2023 caused by the sudden reopening of China’s economy dissipated some time ago.

More worryingly, the government’s 3 per cent inflation target flies in the face of an economy experiencing its worst bout of deflation since the 2008 global financial crisis. In annualised terms, consumer prices have contracted for four straight months while producer prices have been in negative territory since October 2022. Societe Generale says the 3 per cent target is “disconnected from reality”.

Whether it likes it or not, China is in a Red Queen’s race whereby its economy needs to generate more growth just to stand still. While Li said China required “policy support and joint efforts from all fronts”, the measures announced fall woefully short of what is needed to revive growth and restore confidence in China’s economy.

The policy response remains piecemeal and restrained. It is also equivocal and confusing, a source of huge frustration for investors. Even though conditions in China’s manufacturing and services sectors have deteriorated since the economy reopened and market sentiment has worsened dramatically, the government refuses to open the fiscal spigots.

The augmented fiscal deficit – an estimate of all the budgetary resources used to support growth – for this year is expected to be just a bit higher than last year’s level. While Morgan Stanley reckons fiscal policy will become more expansionary later this year as growth disappoints, it believes the additional stimulus measures will be offset by the “continued tightening effects” of deleveraging in the property sector and across local governments.

Therein lies the rub for China’s economy. Each successive effort to boost growth is constrained by Beijing’s aversion to major debt-fuelled stimulus that exacerbates deep-seated structural imbalances and detracts from President Xi Jinping’s prioritisation of technological self-sufficiency and national security.

This leaves the economy, in particular the crisis-ridden property industry, in a precarious position. Any meaningful recovery hinges on a revival in consumer spending, which itself is contingent on restoring confidence in a housing market which accounts for about two-thirds of households’ wealth.

Yet beyond stronger support for subsidised housing and a reaffirmation of its pledge to meet reasonable funding demands from developers regardless of their ownership structure, the government has declined to spell out how it intends to shore up the property market.

That little was said about tackling the main vulnerability in China’s economy – which has now engulfed state-backed China Vanke, the second-largest developer by sales – adds to the weakness and ineffectiveness of the policy response. Nomura said the People’s Bank of China should expand its balance sheet aggressively to deploy funding “to rescue those unfinished property projects”.

The stakes are high for the world’s second-largest economy. The International Monetary Fund points to downside risks stemming from a deeper-than-expected contraction in the property sector that would weigh on private consumption amid weak global demand and geopolitical tensions. It expects growth in China’s economy to slow further to just 3.5 per cent by 2028.

Never mind the prospect of overtaking the US economy based on market exchange rates – China pulled ahead of the United States in 2016 when measured at purchasing power parity exchange rates. The issue is whether a secular downshift in its growth rate will cause China to get stuck in a “middle-income trap”.

While these fears might be overblown, they are fanned by an bearish narrative around China in global markets, one that Beijing has failed to counter. While investors have good reason to be pessimistic about China, they themselves are struggling to make sense of the country’s acute economic challenges.

Why China needs urgent reform to revive middle-class prosperity

Why China needs urgent reform to revive middle-class prosperity

One of the most frequently cited reasons for the loss of confidence in China’s economy is the absence of “bazooka-style” stimulus. Asked what would cause them to increase their exposure to Chinese stocks sharply, 33 per cent of respondents in Bank of America’s latest global fund manager survey, published last month, cited more aggressive fiscal stimulus to support the property market.

However, 22 per cent said maintaining an underweight position was the right strategy while 14 per cent pointed to an easing in geopolitical tensions. Not only does this show there is no clear consensus among investors about what needs to happen to restore confidence, it suggests markets are having serious problems assessing and pricing risks in China.

This is not surprising given the opacity and contradictions in the policymaking process. However, it also indicates investors have yet to come to terms with Beijing’s new policy priorities, especially the shift from an over-reliance on real estate to boosting high-end manufacturing and technological innovation.

Chinese policymakers have a credibility problem as new drivers of growth fail to compensate for the drag from the downsizing of the property sector. Even so, investors have their own credibility issue as they struggle to get to grips with China’s woes and differ among themselves on the causes of the downturn.

Nicholas Spiro is a partner at Lauressa Advisory

8