As US debt piles up, what happens if faith in Treasuries is shaken?

- The sell-off last year was the first sign of something amiss, raising concerns that US government bonds failed to behave like a safe-haven asset

- As central banks start to diversify away from Treasuries and markets reassess their positions, the risk is that Treasury yields could soar, igniting inflation amid tottering debt

The US$14 trillion Treasuries market is the biggest of its kind in the world and by virtue of its size and liquidity is critical to the functioning of the global financial system. As such, it is assumed to be indispensable but this depends upon the financial integrity of the US as a sovereign borrower.

The Institute of International Finance (IIF) has noted that on recent occasions, US Treasuries have “stopped behaving like a safe haven asset”. This has been dismissed as a technicality, yet, the IIF said, “it is at least possible that something more serious may be under way”.

“The US in 2020 saw foreign outflows from Treasuries, which is notable because as a safe haven asset they should have seen inflows at a time of heightened risk aversion. Foreign inflows picked up this year but [they] are not reassuring for a purported safe haven asset.”

US debt markets are at the heart of the network of financial arteries that keep the global economy functioning. They play a central role, with Treasury interest rates providing the fundamental benchmark for the pricing of most financial assets.

The first sign of something being amiss came in March last year when yields in the market shot higher – meaning that Treasury bill prices were falling.

Reality about to pop central banks’ bubble over painless tapering

Flows into the US Treasury market have remained subdued ever since compared with other government bond markets. As the IIF noted, “because a change in how markets see Treasuries would have far-reaching consequences, the US macro picture deserves far greater consideration in the debate”.

The US Treasuries sell-off last year was put down to being mainly due to micro “plumbing” issues, but again, as the IIF said, the episode “has many things in common” with other financial crises such as “a large and unexpected shock” and “liquidity that evaporates when it is most needed”.

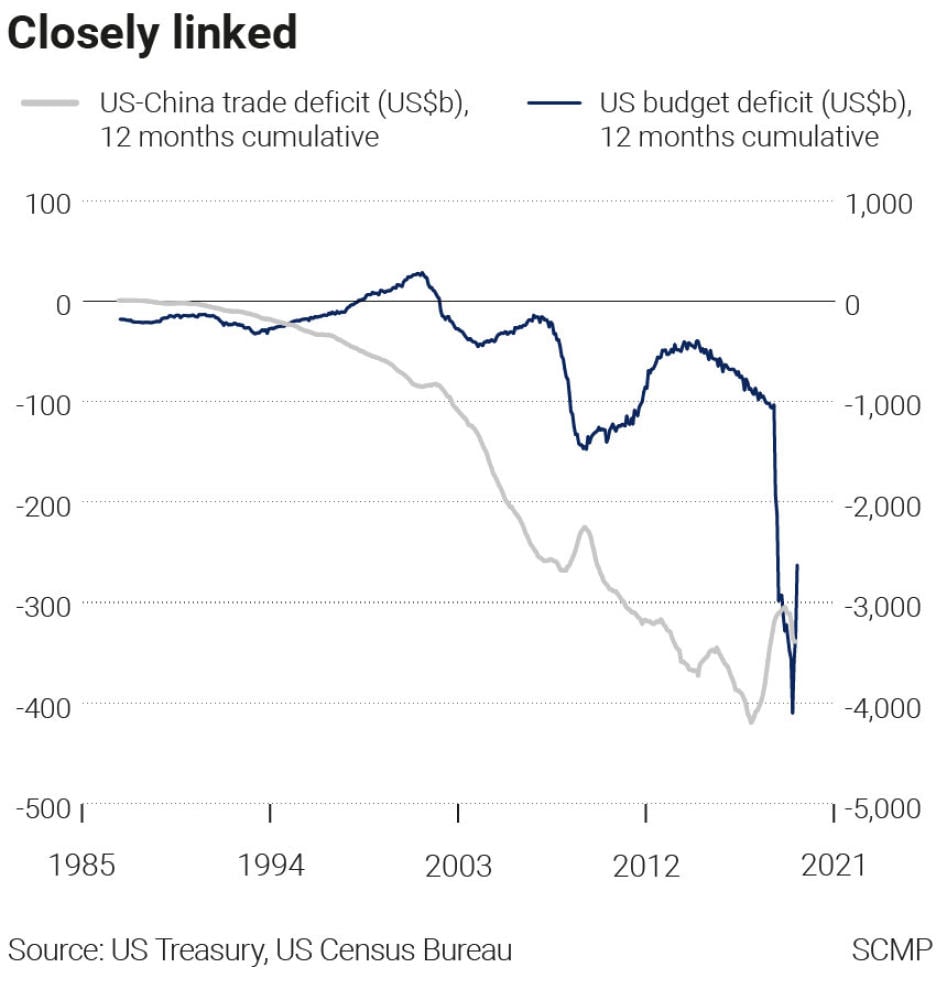

Markets have good cause to be concerned about the size of US government debt. As the New York-headquartered US Council on Foreign Relations observed in an October 1 report, the “US national debt is once again raising alarm bells”.

There are further problems in the prospects of US Treasuries, according to Tran. “So far, the reduction in foreign demand for [these] has been offset by increasing demand from domestic investors, specifically mutual funds, driven by Covid-19-induced domestic savings.”

The key question is “what will happen when US domestic savings decline back to long-term averages and the Fed tapers and stops buying Treasuries. If there is no alternative source of demand materialising, this would contribute to pushing US bond yields higher”.

How the Fed’s tapering decision will reshape global bond markets

Japan is the biggest single foreign holder of US Treasuries with some US$1.28 trillion of them as of June 2020 and is assumed also to be the most stable holder, given Tokyo’s close security ties with Washington, and perhaps the same goes for Britain, which holds about US$450 billion worth of Treasuries.

Anthony Rowley is a veteran journalist specialising in Asian economic and financial affairs