The mixed fortunes of Eurasians: how Hong Kong, China and US viewed intermarriage

In her book Eurasians, MIT professor contrasts attitudes towards interracial marriage in three jurisdictions, and how mixed-race families in Hong Kong were able to grow wealthy despite facing discrimination

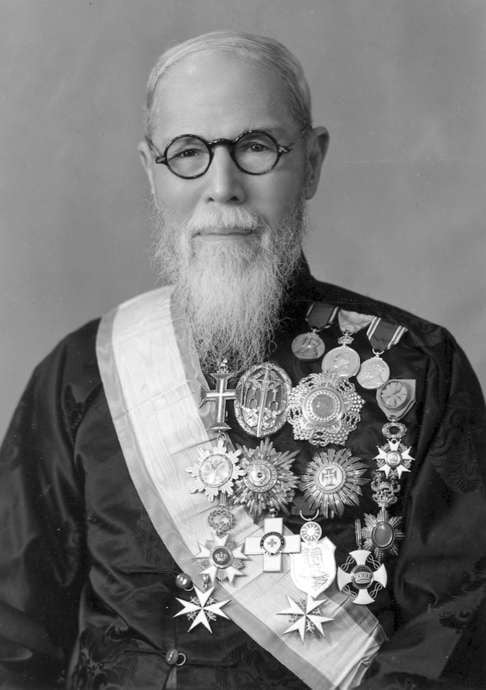

Interestingly, although influential Eurasian businessman Sir Robert Hotung was one of the key founders of Chiu Yuen – he and several family members went to London to petition for a Eurasian burial ground in Hong Kong – he wasn’t buried there. Instead, Sir Robert – the first person with

Chinese blood allowed to live on The Peak – was interred at the Colonial Cemetery in Happy Valley, now known as Hong Kong Cemetery, alongside his first wife. But all of his other direct family members, including his second wife, were buried at the Eurasian cemetery.

Teng was in Hong Kong this month to give talks at The Helena May and the Asia Society – based on research for her 2013 book, Eurasian: Mixed Identities in the United States, China and Hong Kong, 1842-1943.