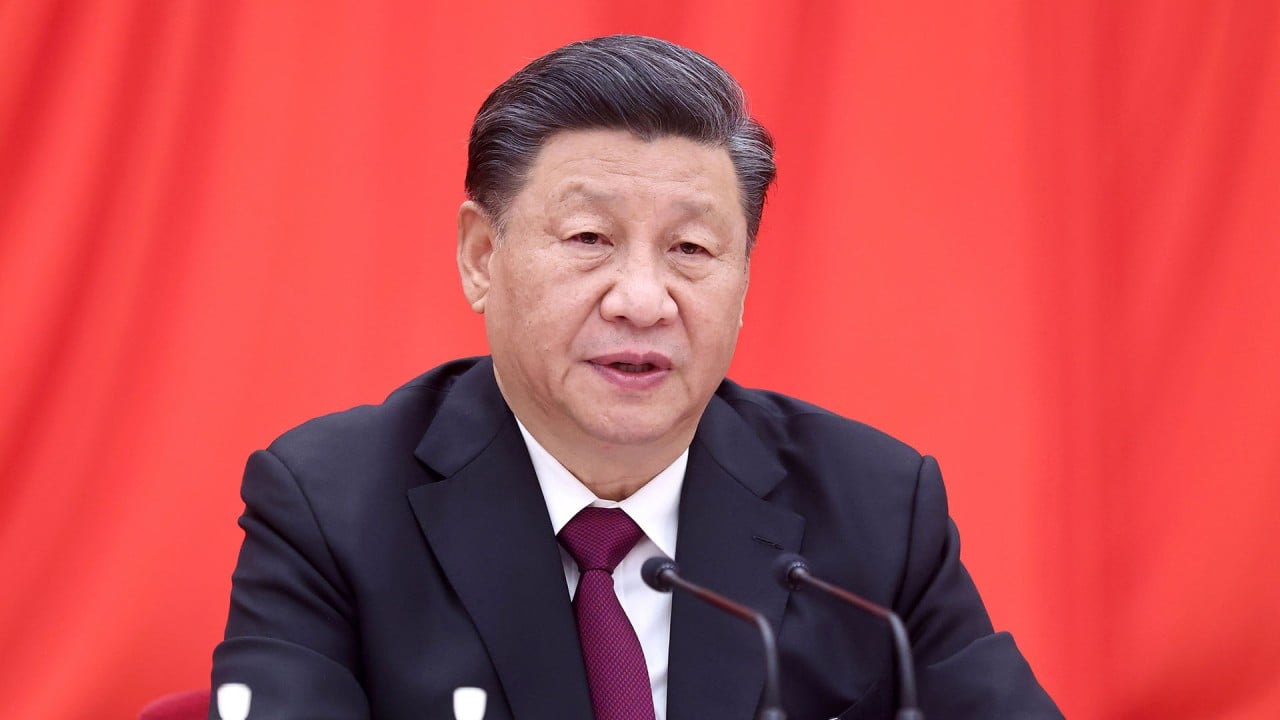

Xi Jinping looks to take China beyond Deng Xiaoping’s ‘get rich’ era with historic third term

- Xi Jinping has stamped his mark on the economy like few of China’s leaders before him. But some experts say important reform has taken a back seat

- How China will realise Xi’s goal of doubling GDP, as well as per capita income, by 2035 will be high on the agenda at this year’s 20th Party Congress

On a cold morning in mid-January, two dozen senior Communist Party officials, wrapped in black coats to protect them against the winter chill, stood solemnly in rows at the courtyard of Guohong Mansion, home to China’s top economic planning agency.

The group had gathered for the launch of the Xi Jinping Economic Thought Research Centre, the 18th research institution set up since the Chinese president’s philosophy was enshrined in the constitution in 2018.

The inauguration reflected not only Xi’s tight grip on power, but showed how central his economic thinking – dubbed ‘Xinomics’ – had become in China’s affairs.

Xi Jinping is about taking China to a new era and a new direction of travel ... not under Deng Xiaoping’s policy line

Since taking office in 2013, Xi has expanded China’s economic influence abroad through the Belt and Road Initiative and introduced an inward-looking economic strategy at home. He has shaken up key industries and stared down US threats of decoupling. As president, he has left his mark on the economy like few before him.

“Xi Jinping is about taking China to a new era and a new direction of travel, under the guidance of his thought, not under Deng Xiaoping’s policy line,” said Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute in London.

“Whether he will succeed or not is of course another matter.”

Xi’s economic philosophy will be in the spotlight at the 20th Party Congress in autumn, where he is likely to be sworn in for a third term.

China’s Covid slowdown raises spectre of middle-income trap

Historically, the event is a chance for Chinese leaders to review past policies and set the direction for new development. The economy, from which the Communist Party draws its ruling legitimacy, often dominates discussions, despite the congress being most well-known for ushering in a new group of leaders every five years.

In 1992, following late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping’s Southern Tour, the party resumed its mission of building a socialist market economy and opening up amid isolation from the West.

In 1997, private businesses were for the first time recognised as an important part of the economy, and entrepreneurs were officially allowed to join the party five years later.

Tackling ‘weak links’

China is at a critical stage of development. Over the past decade, the economy has grown steadily and the country is now on the cusp of joining the high-income club.

On the other hand, it faces numerous headwinds: a demographic crisis, slowing growth, debt, deglobalisation, geopolitical tensions with the West and the coronavirus pandemic.

“We must firmly grasp the problems concerning unbalanced and insufficient development, focusing on improving weak links, consolidating foundations and making full use of our advantages,” Xi told senior cadres in the Central Party School in late July. “New ideas and measures are needed to solve them.”

Helped by Vice-Premier and chief economic adviser Liu He, Xi’s first term between 2013-18 was devoted to addressing domestic problems.

These included high debt, a dwindling demographic dividend, industrial overcapacity and inequality, with structural adjustments and de-risking campaigns high on the agenda.

Faced with uncertainty abroad, Xi pivoted inward with the “dual circulation” strategy in 2020, putting emphasis on China’s huge domestic market and home-grown technology to power future growth. Some analysts said it marked a shift from China’s decades-old, export-oriented development model and participation in the US-led international system.

The clampdown on the country’s big tech players, along with Beijing’s hardline zero-Covid policy, has shaken the faith of many foreign investors.

“Recent sporadic outbreaks of Covid-19 across the country and the corresponding snap lockdowns have taken away one of things most businesses have been able to depend on: a stable and relatively predictable business environment,” said the annual position paper of British Chamber of Commerce in China released in May.

Now, with Xi’s third term in sight, a number of important questions have to be asked about the future of China’s economy. How important will ideology be in development? What will become of Deng’s mantra of reform and opening? And how will Chinese entrepreneurs and foreign investors fare in the years to come?

From rich to strong

Taylor Loeb, an analyst with research firm Trivium China, said the country is moving out of the Deng era of “Getting Rich” into the Xi era “Being Strong”, and his approach looks like a mix of wealth redistribution, a focus on self-reliance and supply chain resilience, decarbonisation, stability and quality growth over quantity.

“The state is the driving force behind realising all of the above,” he said. “China’s economic policies will become more inward looking.”

Market reform in China has stalled under Xi. According to China Dashboard, a joint project between Asia Society Policy Institute and Rhodium Group that monitors Beijing’s reform, there has been either zero progress or actual policy regression in most of the 10 major baskets of reform outlined in November 2013. Among them are SOE restructuring, competition policies, land and fiscal reform.

The assets of state-owned industrial enterprises have grown by 2.6 times to 259 trillion yuan (US$38.3 trillion) compared to a decade ago.

Nicholas Lardy, a senior fellow with the Peterson Institute for International Economics, said Xinomics includes more industrial policy and stronger support for state firms, while paying lip service only to inequality.

The core of Xi’s approach is [that] economics is subservient to politics

He said there was no “serious discussion” of economic reform, but rather a continuation of ineffective SOE policies of the past, such as corporatization, debt-equity swaps and mega mergers.

However, he pointed out that private firms continue to grow more rapidly than their state counterparts.

“Their returns remain much higher, most investment is financed from retained earnings, and private investment has held up remarkably well given the policy environment,” said Lardy, whose 2018 book the “State Strikes Back” charted the resurgent role of the state in the economy under Xi.

Derek Scissors, a senior fellow with the American Enterprise Institute, expected no change to overall economic policy after the congress.

“The core of Xi’s approach is [that] economics is subservient to politics, that economic gains must be sacrificed if they bring political risks,” he said, noting that the Chinese economy began falling short of its growth potential in 2015.

Unfinished reform

Reform may have slowed under Xi, but tackling deep-seated structural issues remains as critical as ever, economists say.

Addressing the country’s urban-rural divide is one pressing task, including more reform of the hukou system, which limits where people can live, work and receive public services. More spending in rural areas is also needed, analysts say.

“Migrant workers and urban residents enjoy different public services. It is urgent to break the dual urban-rural structure,” Cai Fang, a prominent labour economist and central bank adviser, said at the Caixin Forum in early July.

Urbanisation, which draws labour into higher productive sectors, is still regarded by Chinese policymakers as a key way to drive growth and narrow gaps between cities and the countryside.

What you need to know about China’s 20th Communist Party congress

Huang Qifan, the outspoken former mayor of Chongqing, said the next stage of reform must focus on how to build a unified market.

“This is a top priority to unleash the potential of the Chinese economy’s super-large single market and form a strong gravitational field for the world economy,” said Huang, who is now a distinguished visiting professor at Fudan University in Shanghai.

“We need to use a reformist mind and pragmatic measures to eliminate obstacles in the economic system and internal circulation, and expand new market space with new policies.”

Whether Xi will heed these calls is unclear. China is still deeply embedded in the global supply chain and a major draw for foreign investment. But refusing to open up the economy further could come with consequences, according to some analysts.

China’s domestic market remains a powerful gravitational force

David Zweig, an emeritus professor at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, said it is unlikely that economic reform will return to the fore of policymaking in the short-term.

“China’s domestic market remains a powerful gravitational force, pulling in foreign firms despite the risks entering the China market can mean to their own survival,” he said.

“But as the clarity of that threat to the foreign firms and to the economic security of OECD countries intensifies, China’s mercantilism will keep relations with the world far more hostile than would have occurred under a more market-oriented and open strategy.”