How a stray cat from Hong Kong became a hero of Sino-British military clash known as the Yangtze incident

When the HMS Amethyst came under fire from communist Chinese forces on the Yangtze River in 1949, fearless feline Simon kept the spirits of the crew up and the rat population down, his gallant efforts earning him a military medal

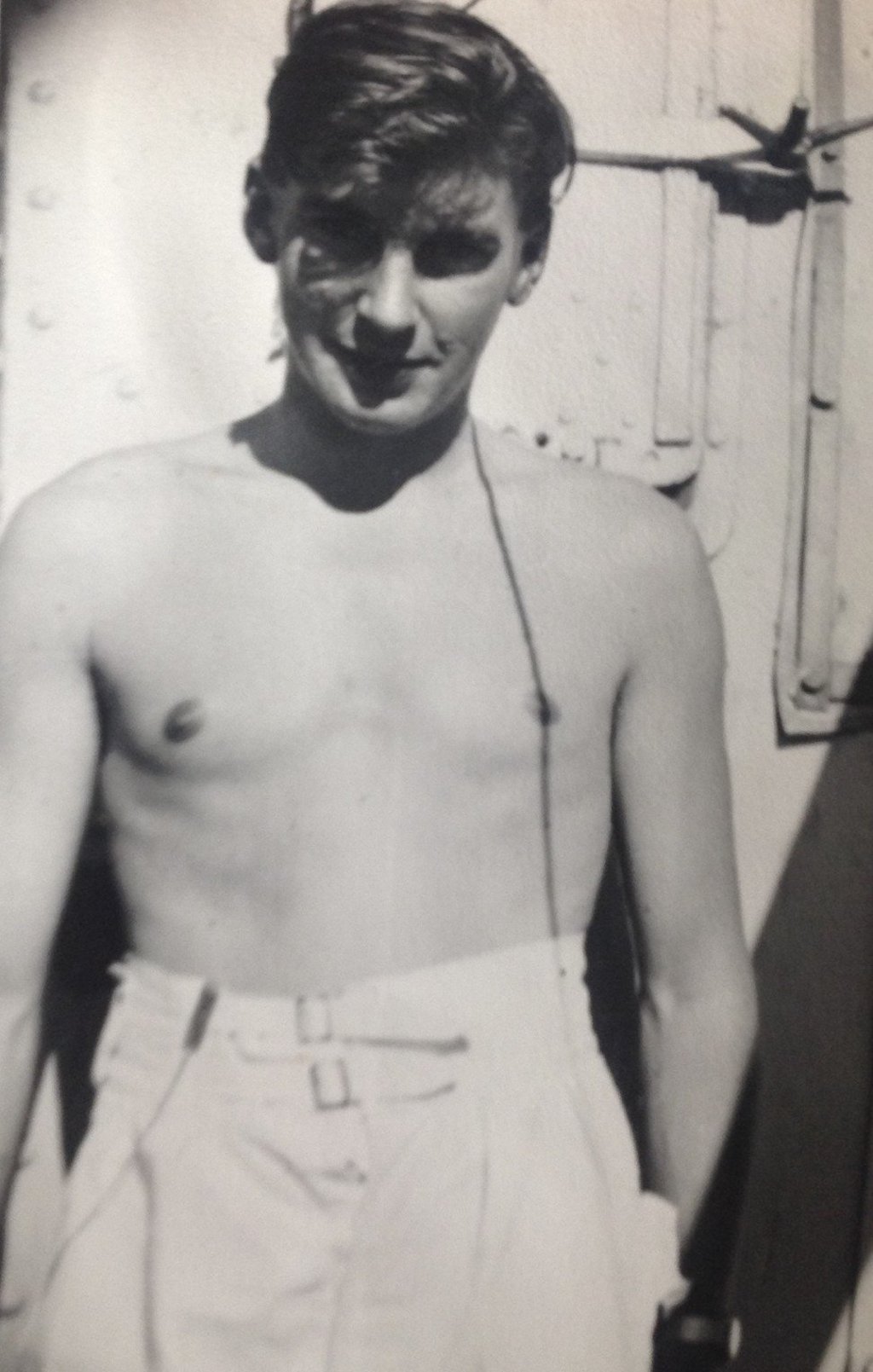

Second world war veteran Stewart Hett wore many hats while serving as a lieutenant on the British frigate HMS Amethyst in Asia in the late 1940s.

“I was responsible for the ship’s anchor and its classified books. As sports officer I organised games, and as education officer I helped the crew with their exams,” says the 91-year-old from his home in Northwood in London.

Simon is the only feline recipient of the PDSA Dickin Medal that honours the work of animals who are heroes in conflict situations. Bearing the words “For Gallantry” and “We Also Serve” on a green, brown, and blue ribbon, it was established in 1943 by British animal welfare pioneer Maria Dickin.

But how did a stray cat from Hong Kong whose heroics inspired the bestselling book, Simon Ships Out: A Heroic Cat at Sea, by British author Jacky Donovan become a celebrated war hero?

Simon’s adventures started in March, 1948, when the skinny black and white cat with green eyes was found wandering Stonecutters Island and smuggled aboard the Amethyst, which was stationed in