When Russian spies tried to infiltrate Hong Kong to destabilise China

- Posing as stewards on Russian cruise liners, KGB agents were accused of setting up an espionage ring to undermine Mao’s China in 1972.

- Russian plot to purchase several US banks also thwarted

As an open port adjoining communist China, Hong Kong under British rule became a centre for covert intelligence gathering. But it wasn’t just the West that used the colony as a spy base. Just ask fans of John le Carré’s espionage novels.

During the 1970s, Hong Kong became known as a vital operating zone for the then Soviet Union’s intelligence agency, the KGB, undertaking what was known in intelligence circles as Line K (anti-Chinese) activities.

Blame for deadly 1953 Pearl River gunboat clash still disputed

After the Sino-Soviet split in the late 1950s over disagreements about communist political doctrine, the KGB’s main Asian target became China. Its intelligence networks in Beijing were dismantled as Russian relations with China soured, so the KGB needed an unofficial base in Asia.

“Because of tight security within the [People’s Republic of China], however, Hong Kong became a more important base than Beijing for Line K operations,” states a recently declassified “top secret” US intelligence briefing document, dated April 20, 1978.

This was the background to a sensational Hong Kong Russian spy story that broke in 1972, making front-page headlines in the South China Morning Post and sending shock waves through the city. The exclusive account, by legendary Post news editor Kevin Sinclair, has since been largely forgotten.

On August 25 of that year, under the headline “Police smash Soviet spy ring in colony”, Sinclair reported how Special Branch police officers had broken up a ring of KGB agents masquerading as captains, cooks and sailors aboard Russian ships visiting the city.

Two Russian spies, Andrei Ivanovic Polikarov and Stepan Tsunaev, had been apprehended, together with two unnamed local businessmen accused of setting up an espionage ring to undermine Chairman Mao’s China.

With typical flourish, Sinclair referred to the organisation as the “floating James Bond of the Russian merchant fleet” and wrote that the two businessmen were “prepared to betray Hong Kong for roubles [sic]”.

In his highly detailed account, Sinclair explained how the ring had been set up in 1969, when the businessmen were groomed by KGB agent Alexander Trusov, who was posing as a marine superintendent at one of Hong Kong’s dockyards. Information obtained by the two businessmen was passed to undercover Russian spy couriers, working as stewards on Russian cruise liners visiting the port.

When the Soviet-flagged passenger liner Khabarovsk – one of about 80 Russian merchant ships that arrived each year – docked at Ocean Terminal on July 17, 1972, both Polikarov and Tsunaev were aboard. Tsunaev was listed on the ship’s manifest as a stoker but was really a Chinese-language specialist and lecturer from a top Soviet university.

It was during a meeting between the two KGB men and one of the businessmen at his home that Special Branch officers burst in. Searching Polikarov, they found a detailed plan for recruiting KGB informers in Asia.

Chinese and Russian spies eavesdrop on Trump’s mobile phone calls, report says

The two spies were marched back to their ship and afterwards an official warning was sent back to Vladivostok. One of the businessmen was repatriated to Taiwan and the other later released due to insufficient evidence. London made formal diplomatic protests to Moscow in a high-profile expression of shock and displeasure.

The degree of detail Sinclair was able to get from his sources is striking. He was even able to obtain photos of the two KGB spies for the newspaper. It was no secret that he had close connections to law enforcement agencies in Hong Kong; he wrote the definitive history of the Hong Kong Police Force, called Asia’s Finest. After his death in December 2007, a commemorative event was held in his honour at the Hong Kong Police Officers’ Club.

The affair, and the role of journalists in intelligence matters, inspired a number of famous fictional accounts.

Le Carré’s The Honourable Schoolboy, published in 1977, opens in the city’s Foreign Correspondents’ Club on a “typhoon Saturday”. A group of disparate and debauched journalists, led by a veteran hack called William Craw, discover that the local British intelligence base has been suddenly and covertly closed down without warning.

The character of Craw is based on veteran Hong Kong-based journalist Richard Hughes, who wrote for The Times of London, The Economist and the Far Eastern Economic Review. Hughes was also the inspiration for Ian Fleming’s character Dikko Henderson, the head of Australian security in Japan, in the James Bond thriller You Only Live Twice.

In Le Carré’s fictional account of KGB activities in Hong Kong, Craw is fed the story by MI6 head sleuth George Smiley as a ploy by MI6 to overemphasise the fractured state of British intelligence services to its opponents.

It is easy to speculate decades later about whether the 1972 Sinclair scoop was fed to him by the Hong Kong and British intelligence services in the same way.

What is interesting about the timing of the real 1972 KGB floating spies’ case was that just five months earlier, on March 13, 1972, China and Britain had re-established full diplomatic relations. This development came weeks after the seminal visit of the then US president Richard Nixon to Beijing.

I have always viewed it as a deliberate penetration by the KGB of the American banking system

Hong Kong continued to be the primary source of foreign currency for its communist neighbour, which was still recovering from the devastating economic impact of the Cultural Revolution. The spies case made the fragile but highly lucrative commercial relationship with China all the more cordial. Chinese officials were known to have expressed alarm about widespread KGB activities in the colony.

It is likely that Sinclair’s story was designed to reassure China of British Hong Kong’s efforts to counter KGB operations and to curry favour with Beijing. If true, Sinclair would not be the only Hong Kong journalist to have played a key role in a major counter-espionage case.

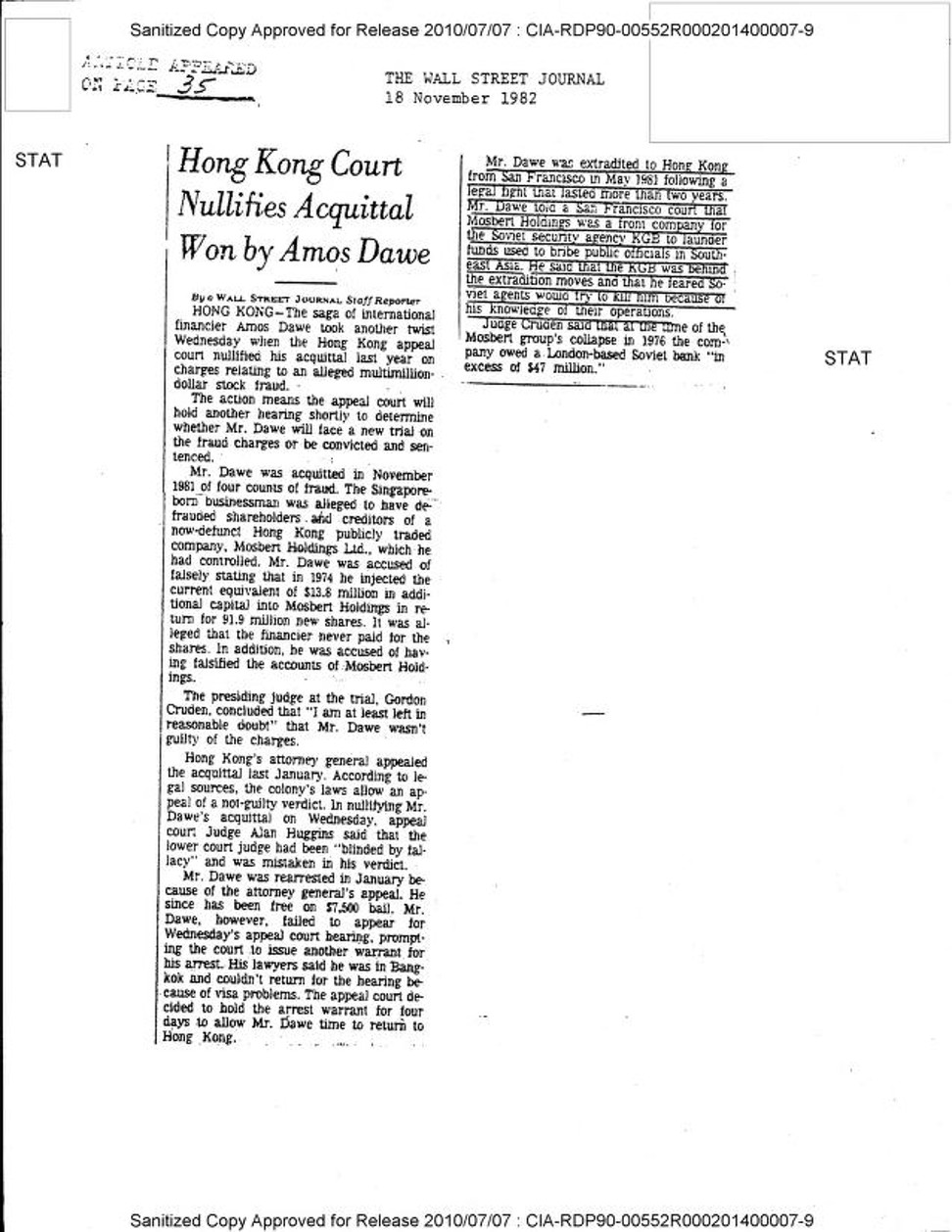

In 1974, Hong Kong businessman Amos Dawe, a Singaporean national with multiple local business interests, including the Hong Kong-listed consortium Mosbert, fronted a daring KGB plan to purchase a number of banks in the United States. According to court documents, the KGB plot was financed by the Moscow Narodny Bank in Singapore, which provided Dawe with a US$50 million credit line.

In 1974 Dawe attempted to purchase US banks with close links to hi-tech companies and their employees in the California area. The KGB logic was brutally simple: why recruit spies to steal vital industrial secrets about America’s new computer-based technology revolution if you could acquire them through banks that lend the companies money?

Dawe successfully bought two US banks in June 1975 for US$7.9 million, but one observant CIA agent in Singapore spotted Dawe’s suspicious lending from the Russian bank. There was nothing illegal about the activity, but this foreign investment was definitely not welcomed by the US authorities.

“I have always viewed it as a deliberate penetration by the KGB of the American banking system,” Bartholomew Lee, a San Francisco lawyer involved in the case in the US, told The New York Times.

The KGB plot was stopped in its tracks in October 1975 when the CIA launched Operation Silicon Valley, releasing the plan’s details to Hong Kong journalist Raymonde Sacklyn. He did not disclose his source, but writing in his financial newsletter, Target, he reported that Moscow Narodny Bank was attempting to destabilise the US banking system. Sacklyn did not respond to a Post request for a comment.

Dawe did a runner, with the CIA, KGB and Hong Kong creditors all in hot pursuit. He eventually agreed to surrender himself in the US, but in February 1979 all fraud charges against him were dropped.

Curiously, the assistant US attorney in the Operation Silicon Valley case was a young Robert Mueller, appointed in May 2017 as special counsel overseeing an ongoing investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 US presidential election.

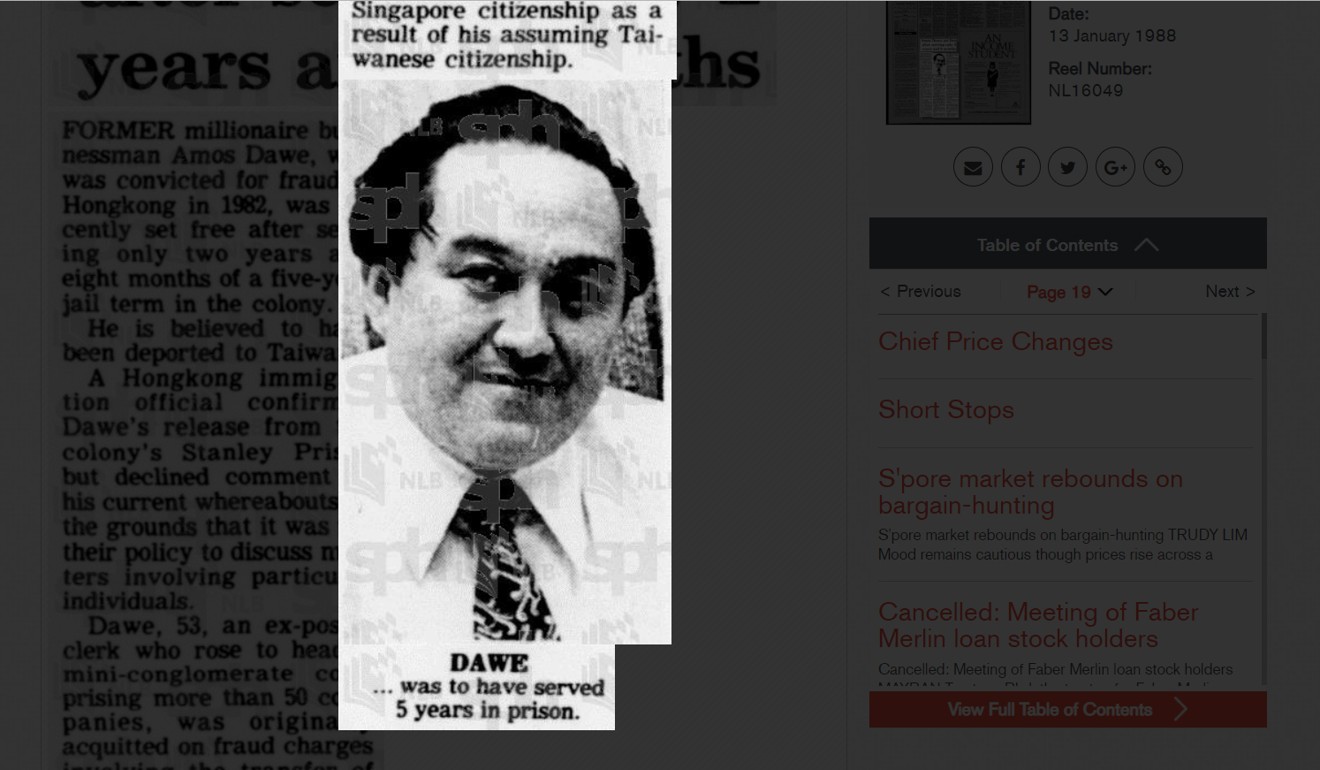

Dawe was subsequently extradited to Hong Kong, where he stood trial on four counts of fraud but was acquitted in November 1981. The acquittal was overturned a year later and he received a five-year sentence.

In a plot worthy of a le Carré bestseller, Dawe skipped bail and hid out in Thailand. An Interpol warrant was issued for his arrest by the Hong Kong authorities. On the run for two years, he was eventually apprehended at London’s Heathrow airport and deported to Hong Kong, where he served two years and eight months of his sentence in Stanley prison.

When Hong Kong was base for famous Asia war photographers

No one seems able to confirm the fate of the mysterious KGB-sponsored tycoon, but it was reported he ended up in Taiwan.

As with the recent poisoning of former Russian double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter in Britain, the authorities in Moscow consistently denied any wrongdoing.