What Hong Kong can do to stop abuse of domestic helpers

- Most abuse cases are not reported by Hong Kong’s 390,000 foreign domestic workers, say many officials

- Axing the live-in rule and two-week deadline to leave the city after a contract expires could reduce helper abuse cases

Foreign domestic workers can be seen in large groups every weekend in Hong Kong, meeting up on footpaths and in tunnels, in parks and open spaces, making the most of their one day off a week. They seem content, even happy, chatting and playing cards, dancing and applying cosmetics.

But behind closed doors, too many of these workers are abused. Many live uncomfortable lives: exploited, expected to work ridiculously long hours, shouted at, and even beaten. Yet Hong Kong’s foreign worker regulations ensure they have difficulty leaving even the worst of employers.

Each year, two consulates in Hong Kong – those of the Philippines and Indonesia – receive thousands of complaints from their citizens who work as helpers, alleging physical, verbal, financial and psychological abuse at the hands of their employers. However, many officials believe most cases of abuse are not reported by Hong Kong’s 390,000 domestic workers.

To meet internationally agreed humanitarian goals – for example, articles 7 and 25 of the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families – and for reasons of basic humanity, it is time to take firm action to change this situation.

Government officials from the Philippines and Indonesia – the nations that send the most domestic workers to Hong Kong – should work swiftly with their counterparts in Hong Kong to protect the safety and well-being of domestic workers in the city, and that includes changing the relevant employment regulations.

One Hong Kong law requires domestic workers to live in their employers’ home, which often means the tiniest of rooms, and sometimes no room at all. This requirement can, and often does, mean the helper is on call 24 hours a day. Yet officials insist that relaxing or eliminating the rule would put pressure on Hong Kong’s job market, transport and available low-cost accommodation.

Domestic worker wins HK$30,000 in damages after being fired over cancer diagnosis

Foreign domestic workers started coming to Hong Kong in 1969; less than a decade later there was discussion within the government of the live-in requirement. The rule was finally confirmed in 2003 to protect the jobs of the local workforce. A survey that year had found a growing number of foreign domestic workers looking for part-time jobs.

Even so, the requirement polarises opinion, even at the highest levels. In 2015, the case of horrendously abused Indonesian maid Erwiana Sulistyaningsih again focused attention on the plight of foreign domestic workers. District Court judge Amanda Woodcock said the tragedy could have been lessened or prevented if foreign helpers were not forced to live in their employers’ homes.

“A choice would make all the difference and may lead to a decline in the number of such cases,” Woodcock said.

But last year a judicial review of the requirement dismissed an application to have it declared unconstitutional. Mr Justice Anderson Chow Ka-ming sided with the director of immigration in dismissing all four grounds of the challenge.

“It cannot seriously be argued that the imposition of the live-in requirement would directly constitute, or give rise to, a violation of the [foreign domestic workers’] fundamental rights,” Chow wrote in a 62-page judgment. “If, after coming to work in Hong Kong, the foreign domestic helper finds it unacceptable, for any reason, to reside in his/her employer’s residence, it is well within his/her right or power to terminate the employment.”

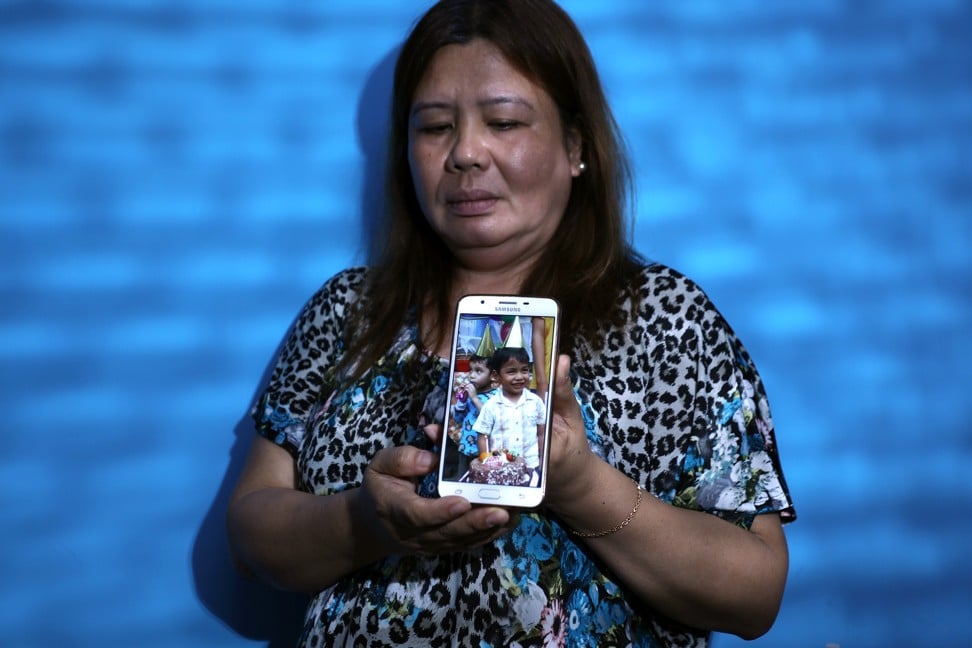

Filipino mothers ask why Hong Kong government has no heart

The much-hated “two-week rule” should also be abolished. It stipulates that foreign domestic workers must leave Hong Kong no more than two weeks after their contracts have ended. It was instituted to prevent foreign domestic workers from working illegally after their contracts had finished, or from “job-hopping”. However, it leaves the helpers at the mercy of unscrupulous employers, because everyone knows how difficult it is to find and confirm new employment in such a short time.

International and local labour and human rights organisations have called for the abolition of the rule for many years. They include the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Amnesty International, Oxfam, and Hong Kong Human Rights Monitor.

Another issue faced is pay. Hong Kong should annually increase the statutory minimum wage for foreign domestic workers to maintain their financial well-being. This would help minimise their need to seek second, informal and illegal job opportunities – behaviour that increases the likelihood of the workers being fined or deported.

Meanwhile, the home nations of foreign domestic workers should ensure all workers heading to Hong Kong have sufficient language proficiency to manage daily communications with their employers. This would help minimise misunderstandings and encourage abused helpers to report their complaints to the authorities.

These nations provide domestic workers with basic training courses before they depart for work in Hong Kong or elsewhere. These could provide information on workers’ rights and resources in host nations, and how abuse should be reported, as well as providing contacts for embassies and consulates, relevant NGOs, women’s refuges and free legal advice if necessary.

Jason Hung was an intern at the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (Unescap). He works as an assistant country director of China at Global Peace Chain and is a visiting researcher at Stanford University