Fung shui masters are giving their traditional image a modern makeover

Fung shui masters and Chinese almanac producers want to appeal to a new generation, writes Elaine Yau

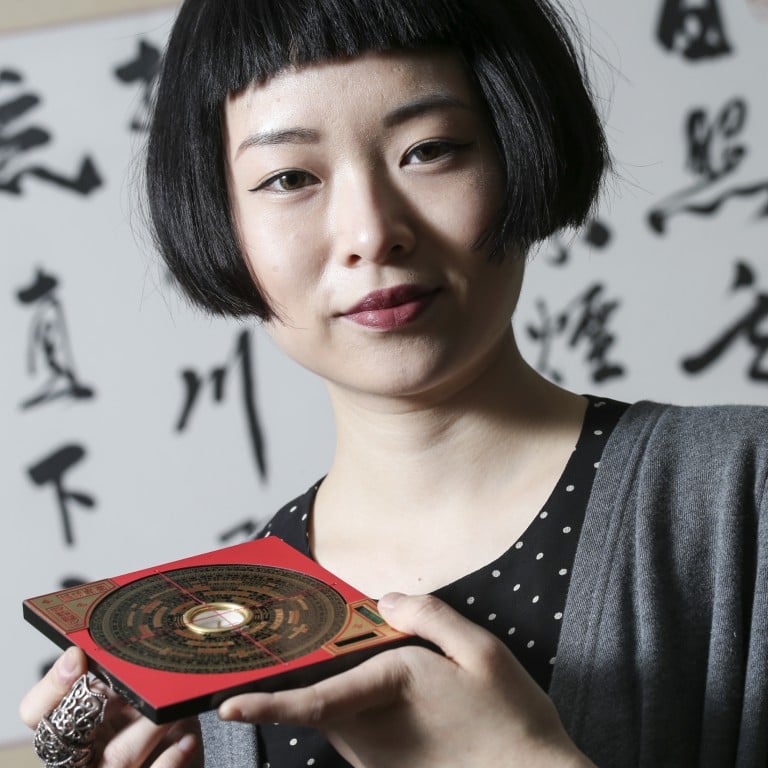

Thierry Chow Yik-tung is determined to bring fung shui into the 21st century, by doing away with the traditional Chinese art’s association with superstition and dowdy customs. The daughter of famed fung shui master Chow Hon-ming, she has been busy recently designing hip talismans, creating social media accounts to boost business, and writing a book that offers quirky fung shui tips.

Chow, 26, studied fine arts in Canada before returning to Hong Kong in 2010 to help her father with his business. She says the image of fung shui needs a makeover to attract a younger generation. “The reason horoscopes and tarot card readings are popular with young Chinese is because they have a modern, hip image. Youngsters will pay a tarot card reader HK$300 to ask only one question. To reach young people, we have to do away with fung shui’s staid and antiquated image,” Chow says.

“After a consultation with a fung shui master, he will suggest the client acquire tools such as ancient copper coins, a golden clock, a copper statue and carpet to decorate the home for a change of fortune. But those tools are in drab colours and the design is dowdy. I come from a design background, and I am creating a line of modern-looking talismans that include necklaces and rings.

“When I go on home visits to provide fung shui and interior design advice, I take pictures whenever I see an auspicious home layout or beautiful furnishings like a gleaming fish tank. I post the pictures on Facebook and Instagram,” she says.

Chow’s first bilingual almanac – Boom Party Almanac 2014 – will be published this month. The almanac will provide an offbeat take on the dos and don’ts for the Year of the Horse. One section, complete with maps, even teaches bar hoppers the best place to stand in a club to boost romantic luck.

Another part focuses on physiognomy, and features illustrations which denote different facial features. It tells readers how to distinguish between a virgin and a crazy woman, and how to avoid a promiscuous male philanderer.

Now working independently of her father – who can command HK$100,000 for a detailed fortune-telling session – Chow provides face- and palm-reading services, and conducts fung shui home visits.

“My bed and study desk used to face different directions every year. If a fan was placed in the wrong part of the house, my dad would fly into a tizzy, saying strong winds would encourage bad luck,” she says.

Although fung shui is regarded by some as superstitious hogwash, Chow claims it is a wide-ranging knowledge system that spans astrology and maths.

“There are many things to memorise. You have to know how to use to use the Chinese gyroscopic compass, understand the yin and yang theories in The Book of Changes, and know how home furnishings should correspond to the alignment of the nine planets. It’s a sophisticated system,” she says.

Chow is trying to interest Westerners in her father’s business. “My dad only knows a smattering of English, because he never studied overseas. After I joined the business, we began to get a Western clientele. I am working on a bilingual company website which will be rolled out this month. I am studying how Chinese and Western astrology can be combined.”

Chow says she has rented a gallery premises in Sheung Wan for a pop-up fung shui store.

“People can come to get birthday readings, or advice about their careers and romantic life for the Year of the Horse,” she says.

Chow is not the only one trying to modernise fung shui. Choi Hing-wah, a fourth-generation family member of Choi Gen Po Tong – the producer of a Chinese Almanac in Hong Kong – aims to update the ancient divination guide with apps and social media.

If a fan was placed in the wrong part of the house, my dad would fly into a tizzy, saying strong winds would encourage bad luck

Choi started working in the family business in 1983.

“I have been helping my dad make it since I was a little girl. Back then, we didn’t have a computer. It was all cut-and-paste work with scissors and glue, with paper slips listing all the favourable and unfavourable factors,” she says.

“Now, with the help of computers, a Chinese almanac, although it is designed to provide predictions for the coming year, can also tell you what you should and shouldn’t do on a specific date 1,000 years later.”

Making the almanac – which involves listing all the things a user should and should not do on every day of the year – is a collective effort for the Choi family. It is still overseen by patriarch Choi Pak-lee, who is in his 90s and has given fung shui advice to former chief executive Tung Chee-wah and property tycoon Li Ka-shing.

“When making the almanac, we do the fixed things first – the lunar and solar calendars, the [timing for the] ebb and flow of the sea, the 24 solar terms [which designate the dates for climate and seasonal changes such as the winter solstice, cold dews and great heat]. These things are very scientific and you cannot change them.

“The metaphysical things – the favourable and unfavourable elements – are added later, after we study all the information and discuss it.”

The idea that a reader should consult a book before deciding when to get a haircut might seem ridiculous, but Choi says the readings and recommendations are based on thousands of years of records and research.

“In the past, people burned turtle shell to prophesy whether to go to war. Turtle shells excavated by archaeologists are filled with such symbols. When emperors from ancient dynasties compiled the almanac, they put in all the records of the prophesies; things like the suitable date to harvest and conduct imperial ceremonies.

“All the favourable and unfavourable elements found in the modern Chinese almanac are based on those records. But the activities have changed to keep up with the times. For instance, there are no more things like ‘what is a good day to dig a well or pick a fung shui grave?’ Now we have auspicious dates for cremations, buying property, and signing contracts instead,” she says.

The Chinese almanac has been printed in Hong Kong since the 1950s. Then, it was a dictionary-like tome that also included handy information.

“It was a guide to life. After the end of the second world war, Hong Kong was swamped with refugees from the mainland. Back then, the almanac contained information on how to conduct business, and even English translations for common Chinese expressions, so that readers could communicate with foreigners under the colonial administration. Parents could find Chinese epigrams and ancient stories about filial piety to teach their kids,” says Choi.

Choi has recently launched some personalised services. For HK$18,000, a buyer can get a personal Chinese almanac which is based on the date and time of his birth and career, and lists all the dos and don’ts for every day of the year.

“Young people will ask us to pick the marriage date, and that costs HK$6,000. Middle-aged people tend to believe that they cannot control everything themselves,” she says. “While they might not see a propitious date as having a critical role in the outcome of an activity, they think that a bit of extra auspicious luck will help.”

English version of Chinese almanac brings good fortune to expat couple

Ken Smith and his wife Joanna Lee are a rarity among expatriate couples because they have consulted the Chinese almanac for significant events in their lives, such as their wedding.

Their passion for the almanac is so great that they have produced an English-language version since 2009.

Now in its fifth edition, the almanac was first produced when New York's Museum of Chinese

in America commissioned an edition for an event celebrating its renovations.

"We put this together as a little gift to be given out at the museum gala, and they also sold it at the gift shop," Smith says.

"It was something the museum put out as an emblem representing the Chinese abroad. It turned out they sold more than they gave away, so I realised there was a market."

Smith, an American who runs a Hong Kong-based arts consultancy with his wife, says they had been following the Chinese almanac for a while before deciding to make an English-language version.

"I tried to get plane tickets from my travel agent and was looking for good rates and good dates to travel.

"The agent had an almanac right there and told me his clients often chose their plane tickets based on it. Apparently this happens a lot.

The couple based their little Pocket Chinese Almanac on a local Chinese edition. Lee, who is from Hong Kong, did the translation.

"Joanna only really started to dig into the almanac when we got married in 2006," says Smith. "But her mum has followed it for years.

"Reading the almanac doesn't immediately make sense, but if you fit it into the bigger picture, it does. If it's a good day to repair fishing nets, it doesn't literally mean it's a good day to go out to fix fishing nets because most of us don't fish today. It means it's a good day to care of your investments and the things that you need to do for your work. Making sure you get your computer cleaned up, that kind of thing."

Smith says readers like the idea that something so ancient can still be part of modern culture.

"There's a holistic view that science doesn't explain everything. And the almanac doesn't explain everything, either. It would be crazy for people to only follow the almanac today. It's part of a grand picture," he adds.

Smith is convinced good fortune has followed them since they have been consulting the almanac.

"If we are going to do a new project, we will look in the almanac. For example, our company is working on a Bruce Lee musical at the Signature Theatre in New York. The preview opens February 4, which, according to the almanac, is a good day for rituals, blessing, and going out and meeting friends.

"It turned out that Elton John [consulted our almanac] for the concert dates on his last tour of China," Smith says.

"We have joked that we should go through the really bad days in history and see what the Chinese almanac says. We might have some intriguing findings."