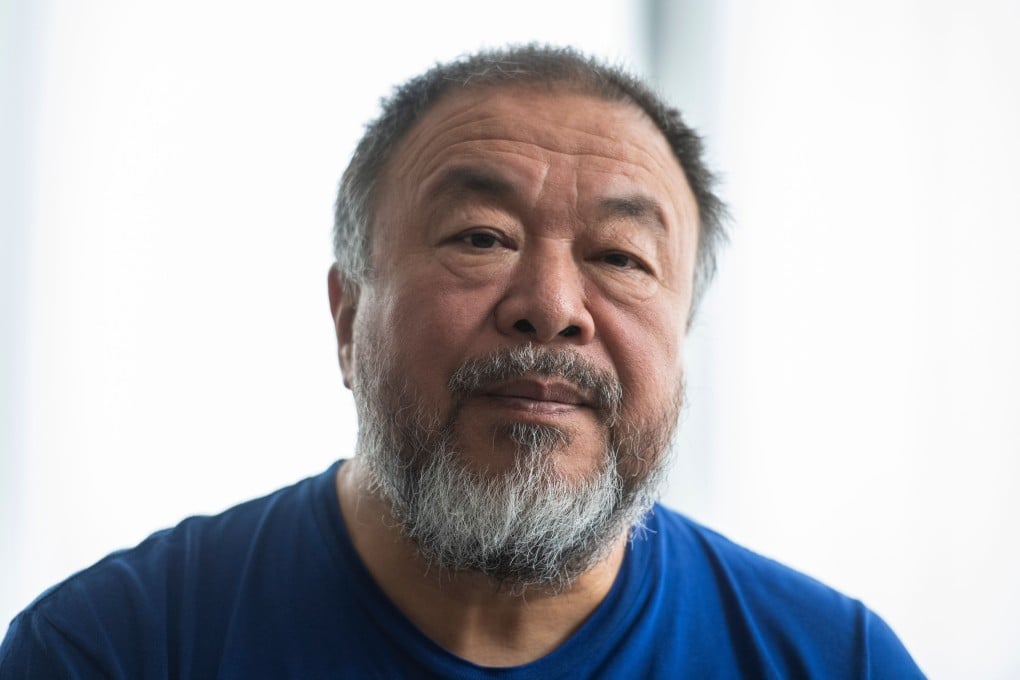

Ai Weiwei says Hong Kong protests part of global freedom struggle, which he’ll reflect in opera production

- Chinese dissident artist says he’s still working out how to express ‘these human struggles’ in upcoming production of Puccini’s opera Turandot

- He also has a team filming a documentary about the Hong Kong protests, which he says are ‘beautiful and sad’ and ‘have affected me emotionally’

The anti-government protests in Hong Kong will be the subject of two new projects by Chinese contemporary artist Ai Weiwei.

In an email interview with the Post, the dissident artist and activist confirms he is working on a new production of Giacomo Puccini’s 1926 opera Turandot, and a documentary about the protests, which he says have had a profound effect on him.

“These events have affected me emotionally and deepened my understanding of the politics of China and Hong Kong. I don’t see the Hong Kong protest movement as separate from the wider global struggle for freedom and democracy, and against authoritarianism,” he writes in the email.

“Thematically, it is not simply about Hong Kong, but about our global political conditions and how we confront issues of freedom and democracy.”

The Teatro dell’Opera di Roma announced in June that Ai will be directing and designing the sets and costumes for a production of Turandot which will premiere in March 2020. (Ai, along with his brother, worked as extras in Franco Zeffirelli’s production of Turandot at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in 1987.)