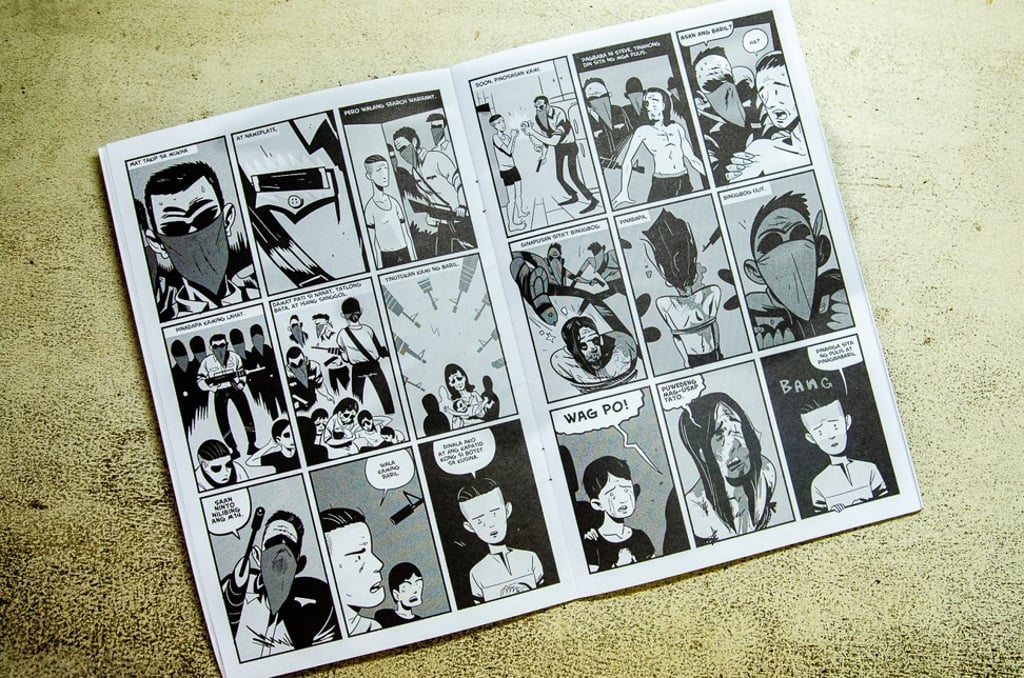

Philippines police killings depicted in comic book to spread word about a controversial crackdown

- ‘Sauron’ features graphic representations of events related to the ongoing Operation Sauron, including the deaths of a number of farmers in March

- The comic, based on witness accounts, contradicts what mainstream media has reported, particularly in Negros Oriental

Sauron, a malevolent presence in J.R.R. Tolkien’s famed Lord of the Rings trilogy, created a powerful ring to win dominion over elves, dwarves and men.

First published in the 1950s, Tolkien’s masterpiece follows the story of Frodo, a hobbit, or halfling creature, who was given the task of destroying the ring to end Sauron’s growing evil in the fictional world of Middle Earth.

Images of the disturbingly malevolent Sauron have found their way into contemporary popular culture. A disembodied flaming eye – the Eye of Sauron – for example, was immortalised by director Peter Jackson in his Lord of the Rings films.

In the Philippines, however, the dark lord’s name is being used by police for an operation to convey the message that they are fighting an evil menace in a crackdown on illegal weapons. In turn, the moniker is also being used by a group of counterculture artists opposed to what they see as the violent operation, in which allegedly innocent citizens have lost their lives.

The operation, called Oplan Sauron, is being conducted by the Philippine National Police Regional Office 7, in partnership with the country’s military and coastguard. It began in December last year.