The story behind Hong Kong’s whale skeleton display, and why a 3D-printed replica will soon straddle the rocks of Cape D’Aguilar instead

- The skeleton of a baby fin whale on outdoor display at Cape D’Aguilar has been battered by typhoons for the past 30 years and some bones are missing

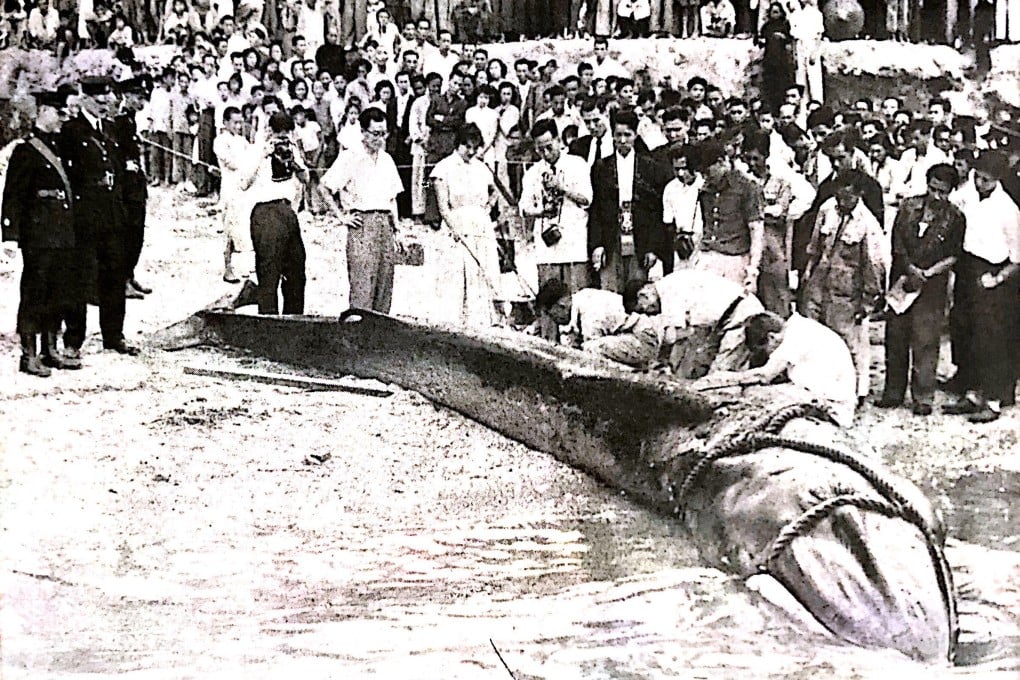

- The whale turned up in Victoria Harbour in 1955. Starving, it was put down by police. Before they could dispose of the carcass, researchers intervened

Perched on a rocky outpost at Cape D’Aguilar, on the south side of Hong Kong Island, is the skeleton of a juvenile male fin whale 6.4 metres (21ft) long, but it’s seen better days.

Erected in 1991, the skeleton has felt nature’s full force, never more so than in September 2018 when Typhoon Mangkhut battered the city with wind gusts of up to 232km/h.

“Mangkhut gave the skeleton a beating, and damaged some of the bones when the waves came crashing over these rocks,” says Philip Thompson, pointing to jagged rock formations that loom large behind the skeleton. “He suffered cracked ribs, a dislodged lower right jawbone and the left hip bone was blown away.”

Thompson, a University of Hong Kong (HKU) research assistant in the division of ecology and biodiversity and at the Swire Institute of Marine Science (Swims), is something of a steward of the skeleton, which stands next to a Swims research facility.

He is leading Swims’ “Restoring Hong Kong’s Whale” campaign, which focuses on raising funds to repair the skeleton and support educational and outreach activities.