Profile | Hong Kong art gallery owner who went from film to photography to opening Blindspot in Wong Chuk Hang

- Born in New York, Mimi Chun moved to Hong Kong when she was five. After she chose to study film at university, her father didn’t speak to her for six months

- She later got into photography, and decided to open a gallery as there were few contemporary art galleries at the time dealing with the medium

I was born on Christmas Eve in New York. My parents both escaped from the Cultural Revolution in China and relocated from Guangzhou to Hong Kong in the late 1960s.

They thought they should give their children a backup plan for the future and that’s why I was born in the US and became a US citizen. My mum’s older sister had moved to New York in the late ’60s, married and settled there. So my parents moved there in the ’70s.

My dad didn’t have a chance to go to university in China but he managed to learn English in Hong Kong, where for a time he shared a flat with Michael Taylor, an American journalist who had also just arrived in Hong Kong.

The two did a language swap. My dad taught Michael Mandarin in exchange for English lessons. My mum left school early and never had an opportunity to learn English.

The Chinese kid

Shortly after I was born, my dad moved back on his own to Hong Kong, where he had better prospects. My mum and I stayed on in New York and lived with my aunt, her husband and their two sons. My mum tried to make some money by sewing at home. I went to a local kindergarten where I was the only Chinese kid.

I remember I was always getting into fights and I hated going to school. For that and other reasons my mum decided to leave New York and to reunite with my father in Hong Kong. That would have been the early ’80s and I was five years old.

Fickle fortunes

We settled in Hung Hom in Kowloon initially, in a very poor neighbourhood. My grandfather was released from jail in China and moved to Hong Kong to be with us. Later, we were joined by one of my dad’s youngest sisters, and then my brother was born. My eldest uncle was also released from jail and he came as well. This all happened within a short period of time after we left New York.

My grandfather was very strong and motivated. He was born into a rich family and everything he and the family had was taken away during the Cultural Revolution. He was in prison for years but he came out fresh. He never held a grudge. He was 104 when he died just a couple of months ago in Guangzhou, where he spent his final years.

My uncle wasn’t as lucky. He was tortured badly in prison. He did some odd jobs after moving to Hong Kong and he was really close to my dad. He just disappeared one day and didn’t come home and was later found dead in a park. It just got too much for him. He was devastated by how life could change so utterly.

Film focus

My dad’s Chinese medicine trading business slowly took off. He didn’t have a background in Chinese medicine, he just stumbled into it. I don’t think I’ve inherited those selling skills. We moved to a bigger space in Pok Fu Lam, on Hong Kong Island.

Later, I got into Sacred Heart Canossian College, a top secondary school that was near our home. Our family was not religious. Sacred Heart used to be an elitist school and very strict – I didn’t fit in and felt like an intruder.

I did badly at my Hong Kong Certificate of Education exams and changed from a top school to a “band 5”, academically-inferior school, where I became a top student. I started taking part in lots of extracurricular activities such as chairing the drama society. I also became interested in photography.

Artist’s dream

Shortly after graduating from the School of Communication in 1999, I joined TVB as a researcher, interviewer and anchor of a new documentary series called iFiles.

It was touching to find out that my dad had secretly recorded my programmes on video despite his objection to my “exposing” of myself on television. After one year, I didn’t want to do it any more because they wanted the programme to focus more on entertainment news. By then the Hong Kong film industry was in decline. So I went to London and spent a year studying for a postgraduate diploma in photography at the London College of Printing (now the London College of Communication).

That’s when I went to Venice for the first time. (I’d gone to the 2002 Venice Biennale; who would have thought that I would be at the 2022 Venice Biennale supporting one of my gallery artists, Angela Su, who is representing Hong Kong!) I tried to find somewhere that would show my work after moving back to Hong Kong but no gallery would show young local artists back then, let alone photographic works.

That was perhaps the first time I thought about the possibilities of an art space/gallery that was unlike others.

The other side

After the Oriental Daily, I got into public relations. I subsequently worked for the Swatch Group and was doing the publicity for its Omega brand, which was the official timekeeper of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. For that reason I started travelling to Beijing ahead of the Olympics.

One of the reasons I wanted to start a gallery was my exposure to the early days of the 798 Art District. I felt I didn’t have the artistic talent to practise art but I started to see the other side – realising there were few contemporary art galleries dealing with photography and that I could work with artists.

After 2008, I quit my PR job and started the gallery, though it was unclear at that time that it was going to be a commercial gallery. I also married my husband, Chris, in 2008. It is always like that in life; the most important things always collide and happen at the same time. He wanted to have a place where he could do things in music. I wanted somewhere where I could have a darkroom.

We embarked on a search for industrial space. We found the current Blindspot Gallery space in the Po Chai Industrial Building in Wong Chuk Hang.

Luck out

With two spaces to run, I had to hire someone, and that someone was Lesley Kwok, who this year has been Angela’s studio manager and exhibition producer while she prepared for the Venice exhibition. We used to do eight to 10 shows in SoHo each year. It was madness. We closed the SoHo space in 2014. The opening of PMQ caused our landlord to triple the rent. More galleries moved to Wong Chuk Hang just before and after the MTR opened in 2016.

Hong Kong identity

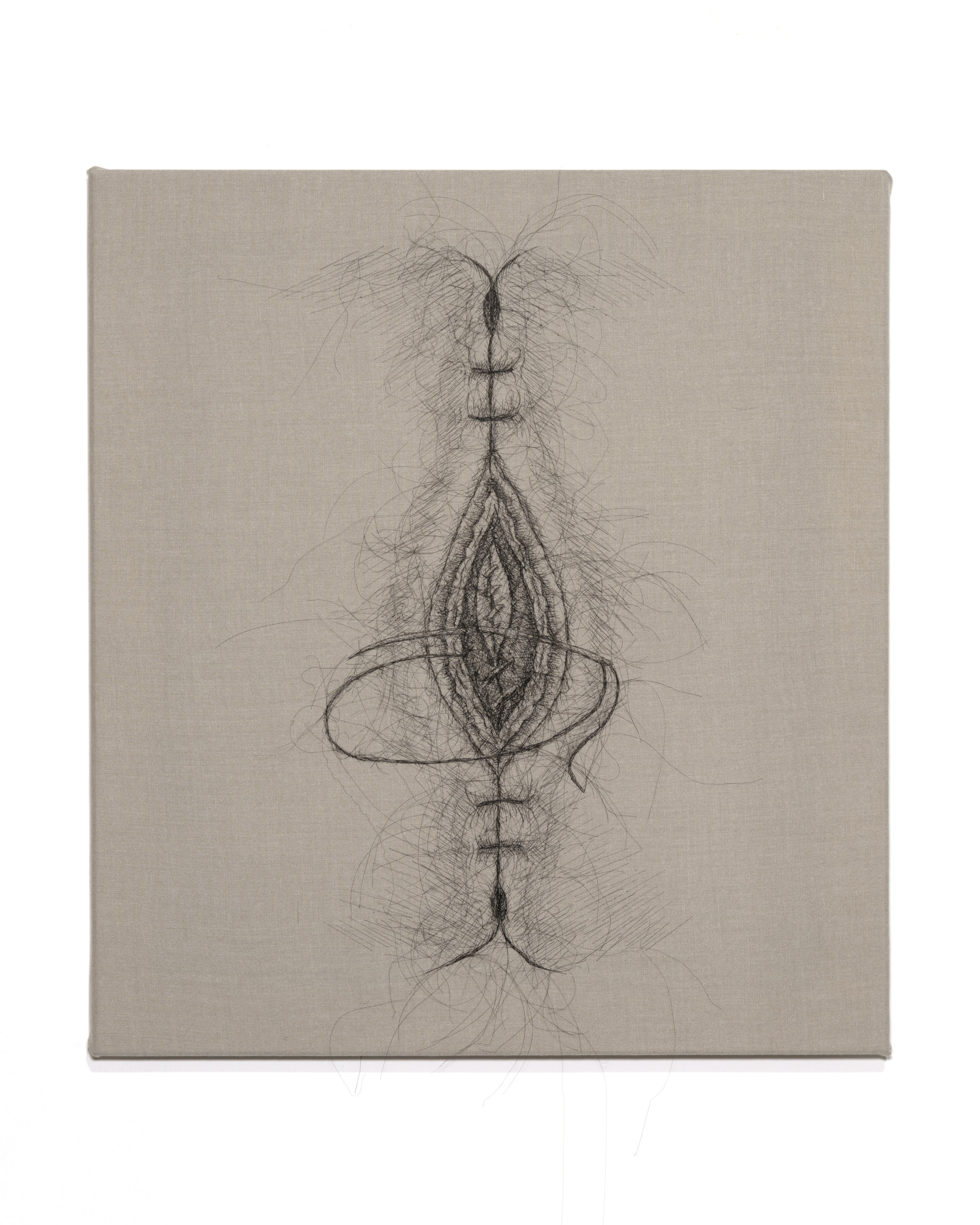

My son was born one year after the gallery opened. If I had a kid earlier I wouldn’t have opened the gallery! There’s so much work. We also have a daughter, who is eight. Nick Yu, the associate director, joined Blindspot Gallery in 2016 and has brought into our programme a focus on art and artists on the topic of gender.

Sin Wai-kin, the London-based artist who has just been shortlisted for this year’s Turner Prize, first showed at our gallery in 2019 when we had an exhibition of eight female and non-binary artists called “Holy Mosses”. People know more about Hong Kong now and realise we have our own cultural identity and that our art scene is distinctively different from other parts of China or Asia.

There is concern over censorship and politics but the most profound art can come out through efforts to work with these new restrictions. I am not too pessimistic about Hong Kong.