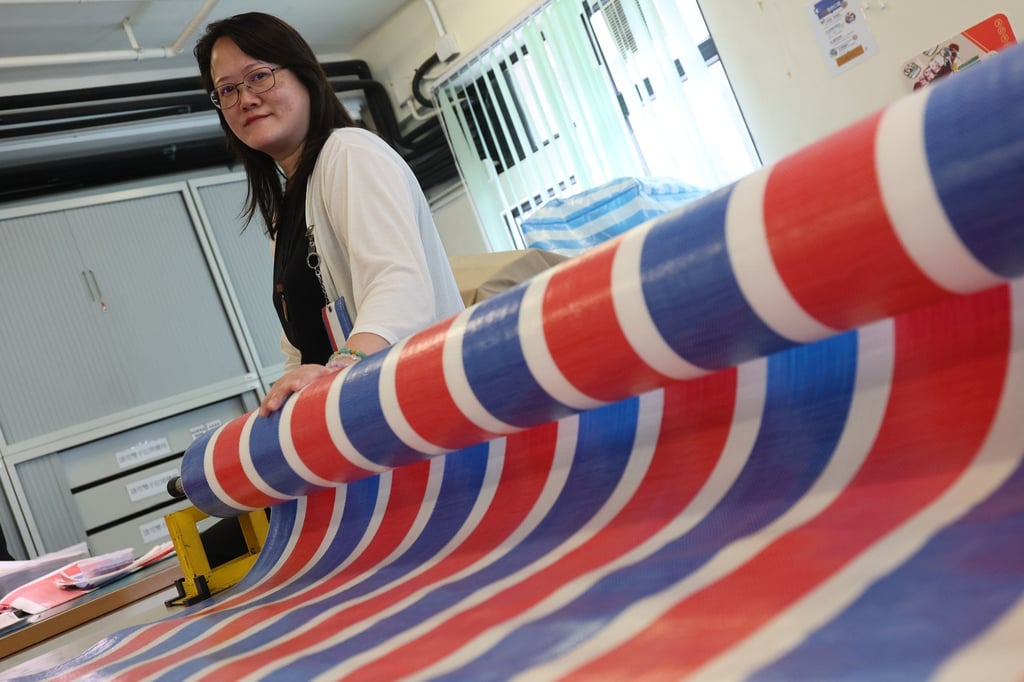

How Hong Kong’s red, white and blue bags and striped fabrics are giving people recovering from mental illness a sense of pride and hope

- Red, white and blue bags and striped tarpaulins and market stall canopies have long been a common sight in Hong Kong and hold a special place in people’s hearts

- At workshops in Kowloon, people recovering from mental illnesses make items from the material that are sold citywide and online via a concept shop

At a sheltered workshop in Hong Kong’s Sham Shui Po district, Wong Pui-wan skilfully steers a sewing machine over a piece of striped fabric.

The 66-year-old is putting the finishing touches on a bag, one of the many items made at the workshop run by the New Life Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association, a non-profit that helps people recovering from mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and depression.

“We provide a holistic approach so people can achieve self-reliance and become integrated into society,” workshop manager Carmen Au says.

Social connections – vital for people in recovery – are also made here, Au adds.

Without the workshop, Wong says she would probably be sitting at home in silence. “For a long time I was too scared to talk.”

Next to Wong is 62-year-old Connie Ku, who was lonely and depressed before the workshop gave her hope.