Students of India’s Film and Television Institute strike over dubious appointments to the school’s governing body

Vocal students of India’s Film and Television Institute are striking over their government’s appointments of loyalists with fishy credentials to the state-funded school’s governing body

As battlegrounds go, the leafy campus of India’s premier film school must count among the more graceful, with its rows of tidy bungalows gently shaded by neem and tamarind trees.

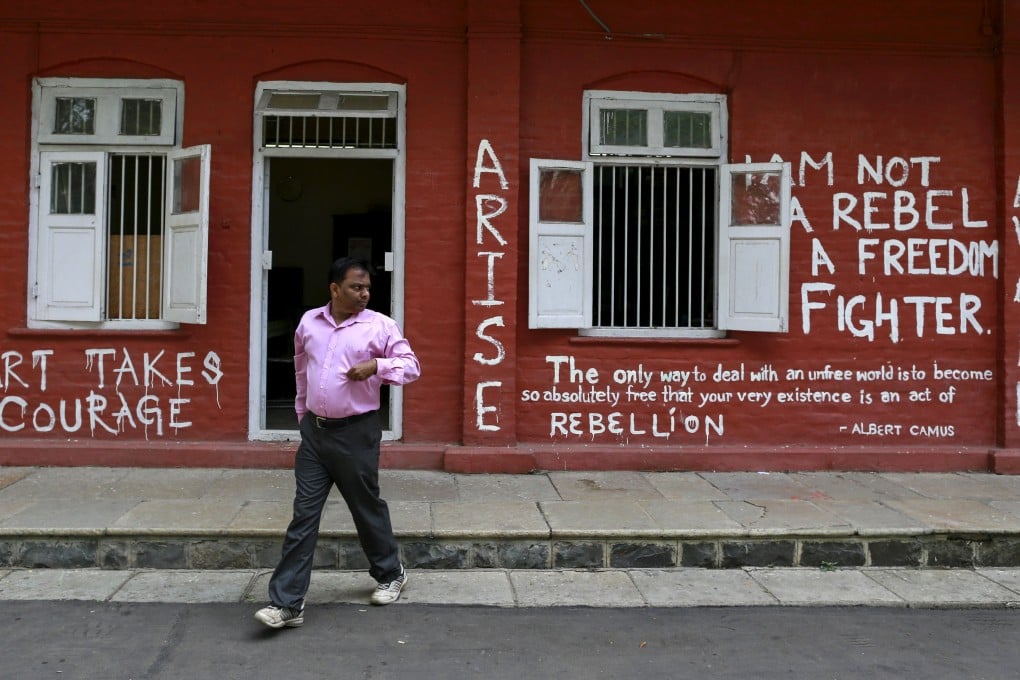

Yet there is no mistaking the foment at the Film and Television Institute of India. Hand-painted slogans snake across building walls, quoting Albert Camus and Martin Luther King. Outside the cafeteria, students smoke hand-rolled cigarettes, talking of fascism and free speech.

For nearly three months, the roughly 400 students here have been on strike, protesting the Indian government’s appointments of loyalists with dubious credentials – including an actor who appeared in B-grade adult movies and a maker of right-wing propaganda films – to the state-funded school’s governing body.

“They want to turn the institute into a factory for their political views,” says Ranjit Nair, a directing student helping lead the protests. “We totally reject that.”

The skirmish is over not just the future of the foremost film academy in the world’s biggest movie-making nation, a breeding ground for Oscar winners, expert technicians, darlings of the international festival circuit and stalwarts of Bollywood and India’s thriving regional cinema.