Digital books may be the answer to the high price of school textbooks

Can an e-textbook campaign help check rising costs for parents under pressure, asksElaine Lau

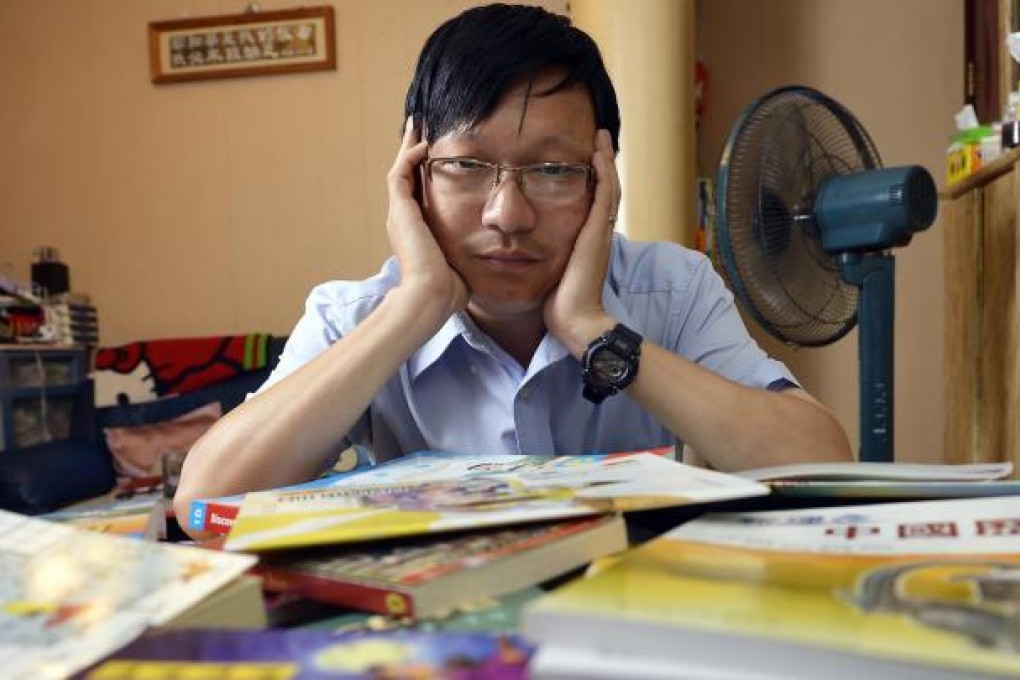

Raymond Jao Ming, a school technical officer, is relieved that he has just one child still in school. His youngest daughter is about to start Form One and her textbooks will cost him HK$2,800 - not a hefty sum compared to what many middle-class parents spend on their children, but a significant dent for lower-income families.

It was even tougher going when all his three children were at school. Jao resents the expenditure, saying that textbook costs have continued to rise while the content has remained largely unchanged.

"Most of the 20 books for my daughter are new editions, which means we can't rely on second-hand books. When my three children were studying, we had to scrimp to pay for textbooks," he says.

Parents' representatives have been engaged in a tussle with publishers over rising textbook prices in recent years. This year has been no different. According to a Consumer Council survey of 944 textbooks commonly used in Hong Kong schools, costs have risen 3.8 per cent from last year for secondary school titles, and 2.1 per cent for primary titles.

Jao, who represents parents on a government advisory body on school textbooks, condemns publishers for unscrupulous practices.

The new editions cost more, but usually involve only slight adjustments. Because the tweaks result in pagination changes, Jao says, this stops students from using second-hand textbooks because teachers refer to particular pages during lessons. Packaging the books (or "bundling", as it is often called) with additional materials like CD-roms and flashy exercise sheets also pushes up the costs. "Many of the materials are left unused at the end of the term," Jao says.