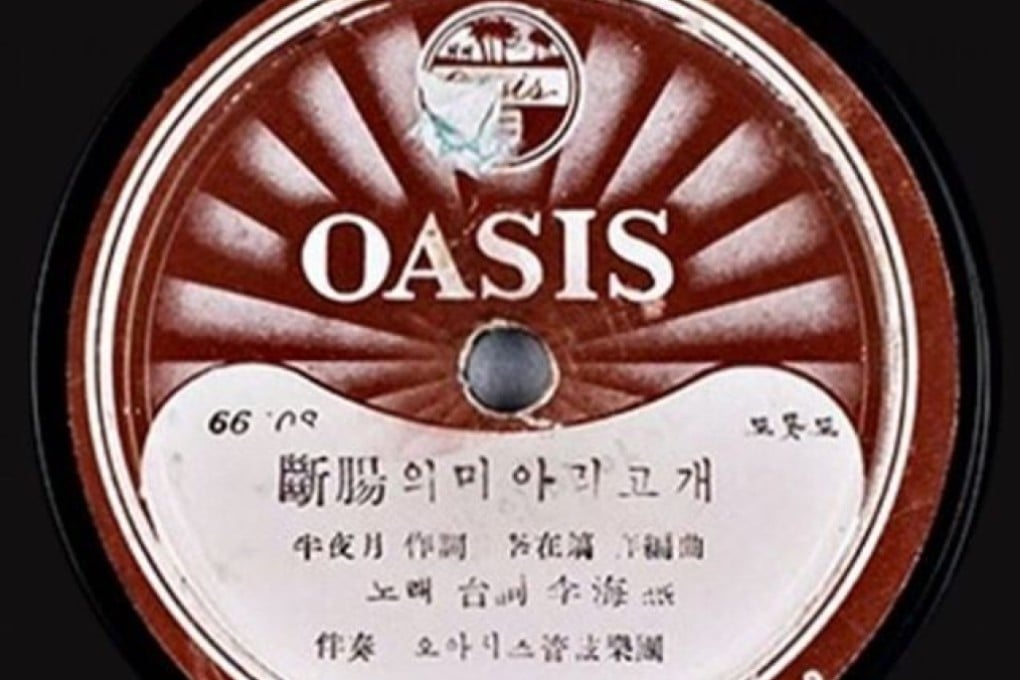

Korean pop music archive digitised and reissued for vinyl lovers – it’s ‘our living history of K-pop’, record company boss says

- Decades worth of master tapes, used to produce vinyl records, have been digitised by Oasis Records Music Company, established in 1952

- With vintage Korean pop making a comeback, the company is making new vinyl pressings of some of the music that was a precursor to today’s K-pop

By Park Ji-won

The division of labour among professionals unrivalled in their respective fields is considered one of the factors that has led to K-pop’s global success. Entertainment companies focus on seeking out and training aspiring young singers while composers write the songs and recording companies handle production.

But several decades ago, there weren’t any specialised workforces in the domestic music industry. All work was streamlined under one single record label – and they wielded enormous power.

Notably, the labels recorded master tapes, which were then recorded to vinyl records and other formats. Vinyl records were the preferred choice of industry workers and music lovers, but they gradually disappeared after the introduction of more convenient formats such as cassette tapes, then CDs and now digital music.

These early recording companies declined as they were slow to respond to ever-changing technology. They refused to adapt to the fast-changing industry landscape and gradually disappeared. Their master tapes also vanished due to fires, negligence or various other reasons. So the number of domestic vintage vinyl records slowly dwindled after the 1990s when vinyl production shut down.