DC Comics Asian-American superhero anthology celebrates Asian Pacific American Heritage Month

- The DC Festival of Heroes: The Asian Superhero Celebration anthology features characters like Monkey Prince, the son of Journey to the West’s Monkey King

- Anti-Asian bigotry, induced by Covid-19, was raging in the US when it was being produced and the book includes xenophobic episodes that Asians can relate to

On the surface, Marcus is a socially awkward Asian-American kid who doesn’t have many friends – but, like Batman, whose life as playboy Bruce Wayne hides his superhero identity, Marcus has a superhero alter ego.

Marcus is Monkey Prince, the son of Monkey King from the Chinese literary classic Journey to the West . And, like Batman, Monkey Prince is hell-bent on taking down villains.

The newly minted Asian-American superhero is part of a comics anthology published by DC Comics to celebrate Asian Pacific American Heritage Month in May. The DC Festival of Heroes: The Asian Superhero Celebration features new characters like Monkey Prince, as well as sequels and the origin stories of various DC superheroes.

Sounds, written by Mariko Tamaki from Canada, stars Batgirl alias Cassandra Cain as a taciturn girl with a speech impediment who thinks words and sounds are a distraction in her mission to rid the world of deviants.

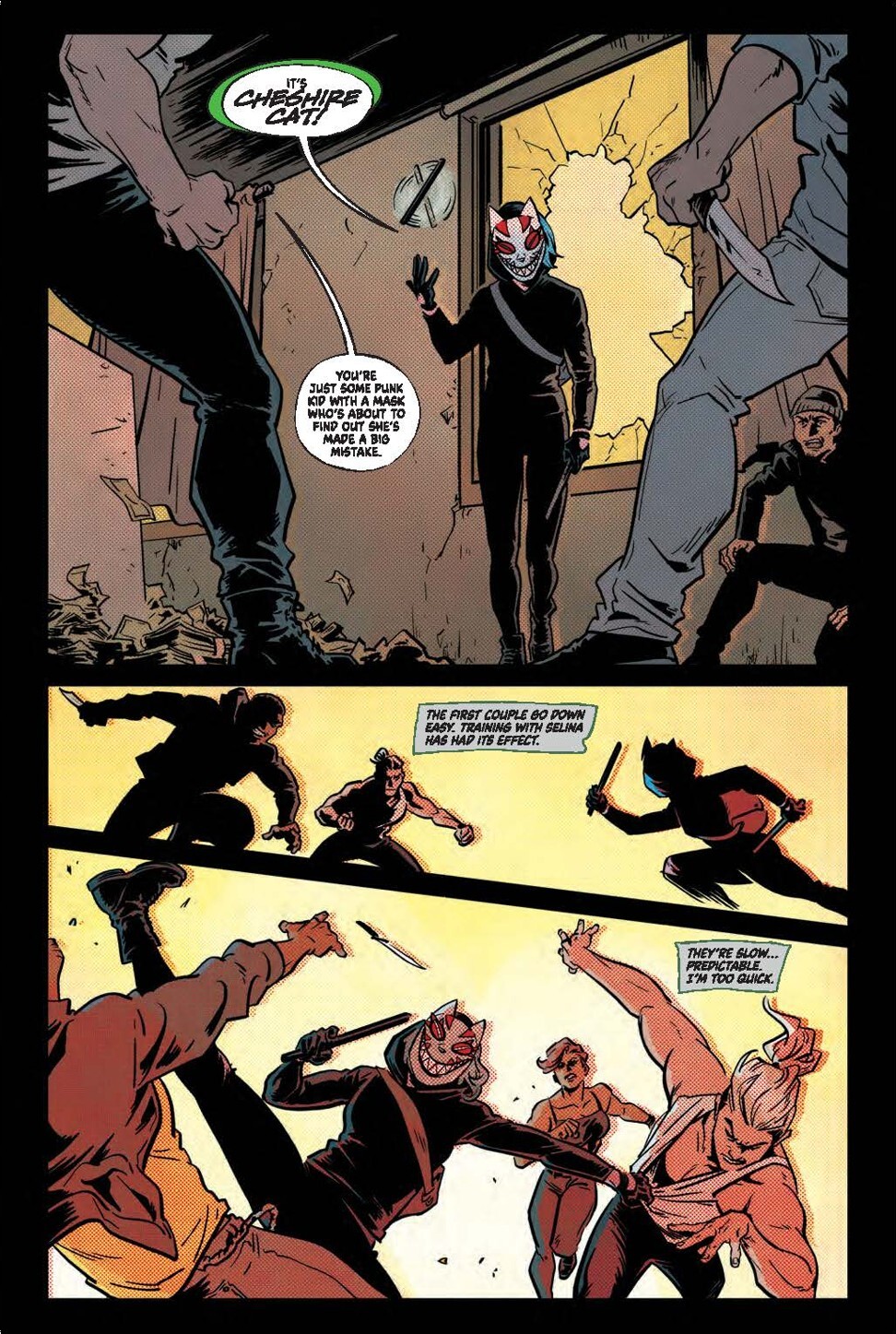

In Masks, written by the current Catwoman series author Ram V, a girl named Shoes becomes the protégé of Catwoman. Shoes sports a mask with a Cheshire cat smile when she fights her enemies.

Jessica Chen, who edited the anthology, says she found the work cathartic because the stories are set in a fantasy world filled with Asian-American superheroes where the oppressed can get their revenge.

“It validates some of our real experiences,” she says.

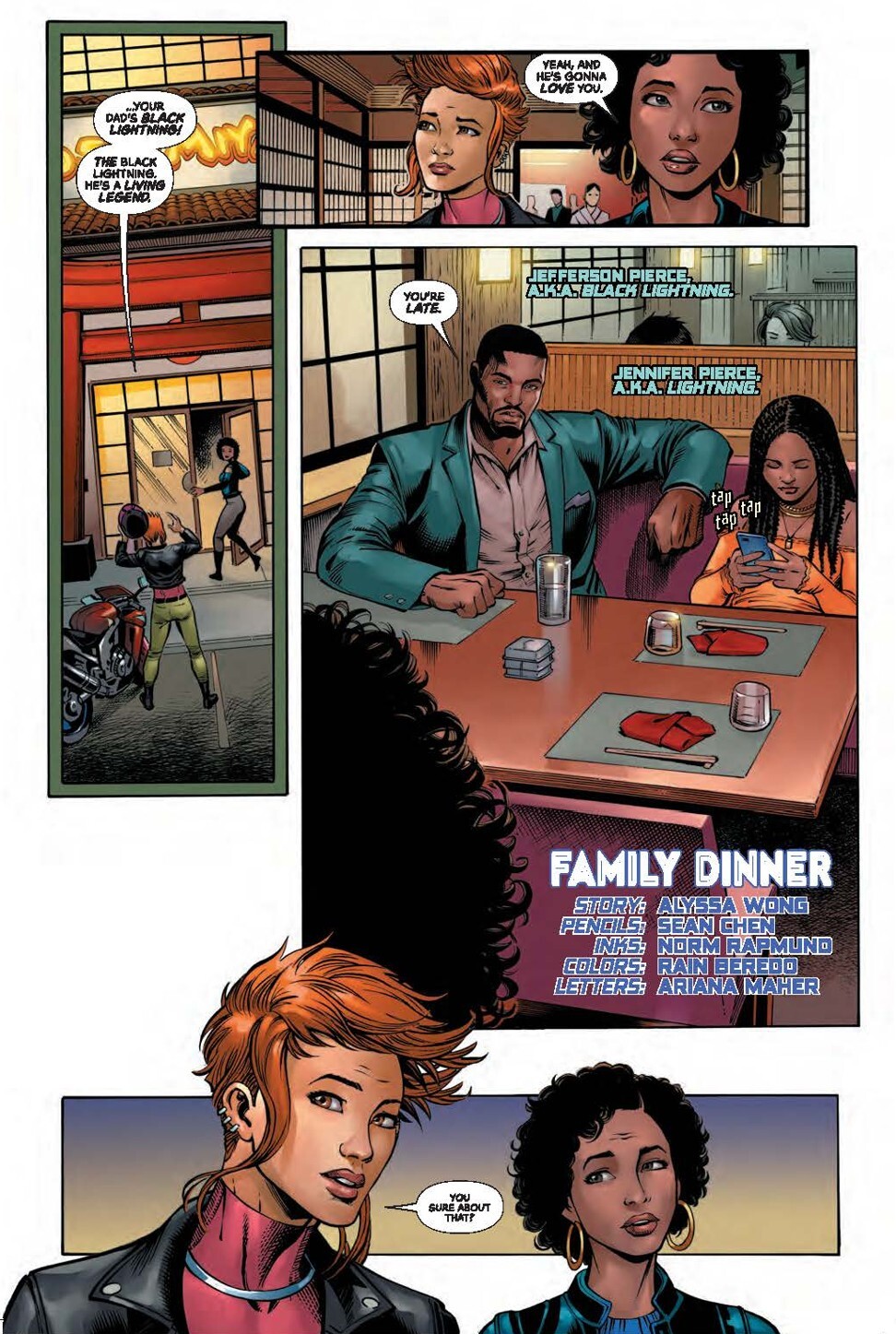

When selecting the superheroes to fill the anthology, Chen says she chose ordinary characters with feelings that readers could relate to. In Family Dinner by Alyssa Wong, a lesbian of colour named Anissa Pierce, alias Thunder, takes her Korean girlfriend to meet her parents.

“For Family Dinner, whether you are in a straight or gay relationship, bringing your partner to meet the parents, especially Asian parents, is so scary,” she says.

Graphic artist Gene Luen Yang, who wrote The Monkey Prince Hates Superheroes, says while Asians have been a part of American comics since Superman was created by DC Comics in 1938, they have evolved from the stereotypical criminals and clowns of earlier days into three-dimensional heroes.

Yang says that the character Chop Chop, in a DC Comic about the pilot Blackhawk and his team of Second World War ace fliers, is another stereotype. Chop Chop is Blackhawk’s Chinese cook.

“You’re supposed to laugh at the typically Chinese things about him,” Yang says. “He has very slanted eyes, buck teeth and he is very short. He’s basically a walking, talking joke.”

Yang says there have been a number of Asian-American comic creators in the industry for many decades but they have always been behind the scenes and unable to make editorial decisions.

“The big difference now is that we are getting to tell our own stories of Asian-American characters being fully fleshed out human beings.”

In 2016, Yang – a two-time National Book Award finalist for the graphic novels American Born Chinese (2006) and Boxers & Saints (2013) – created a new Chinese Clark Kent called Kenan Kong, a 17-year-old kid from Shanghai with superpowers.

“Kenan Kong was really fun to write, as he’s not a kung fu master,” Yang says. “He doesn’t have a Chinese sword or nunchucks. His superpowers are not related to his Chinese-ness.”

Since 2020, Korean-American graphic artist Jim Lee, who in 1998 sold his studio WildStorm Productions to DC Comics, has led DC Comics as its sole publisher. To Yang, this represents the culmination of Asian-American graphic artists’ quest for equal career opportunity.

“That’s a fairly new thing that we’re in positions like that,” he says. “Jim is the number-one of comics in all of American publishing history.

“My dad was an engineer. All of the Asian-American engineers of his generation have the same experience of training somebody who is white and who eventually became their manager. With Lee and Jessica Chen, we are finally seeing Asian-Americans rise to decision-making positions.”

Bernard Chang, who created the art for Monkey Prince Hates Superheroes, says the opportunities available for his generation of Asian-American graphic artists allowed him to pursue his dream job.

“My parents always wanted to push me to become a doctor, a lawyer, businessman or a teacher,” he says.

“But I wanted to become an artist. After my first professional job, I saved up my money for a whole year and bought my mum a house. I showed her that I can successfully support myself and her through this career and art.”