Elderly people are dying on waiting lists for Hong Kong care homes, and proposed changes may make things worse

- Elderly applicants have to wait more than three years for a place in a residential care home in Hong Kong

- Planned changes to the system for assessing their care needs could make things worse, social workers, academics and elderly people themselves fear

Once a driver, Mr Chan, 77, has been confined to a wheelchair since he lost his footing and injured his spinal cord. For the past 15 years, his wife, a retired garment worker also in her 70s, has been his only carer.

Each day, besides handling household chores, she changes his diapers five times and bathes him at night, single-handedly lifting him in and out of the shower. The couple do not want to reveal their full names.

“I don’t know where I have found the strength,” says Chan’s wife, recalling how, for a few years before they moved into public housing, she even had to carry his wheelchair and help him down five flights of stairs.

This has taken a physical toll, and she finds it increasingly difficult to muster the energy to keep carrying out these tasks. She has cataracts in both eyes, and her legs are increasingly growing weak – twice recently, they gave out unexpectedly, causing her to fall in the street.

The Chans’ plight is just one example of the struggle elderly people face in Hong Kong today despite the government’s pledge to help those entering the autumn of their lives.

To relieve demand on institutional care, since 2014 the government has embraced the concept of ageing in place, meaning elderly people stay in the comfort of their homes and rely on home services or day care centres for support.

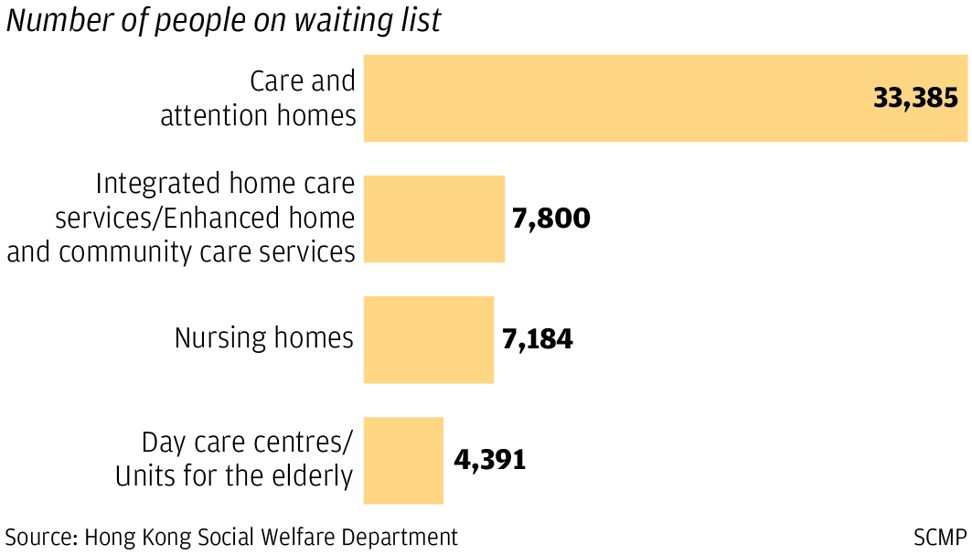

However, the lack of resources allocated to both mean that, for many elderly people like the Chans, neither is feasible. Most elderly people spend years on waiting lists for care services and places in care homes.

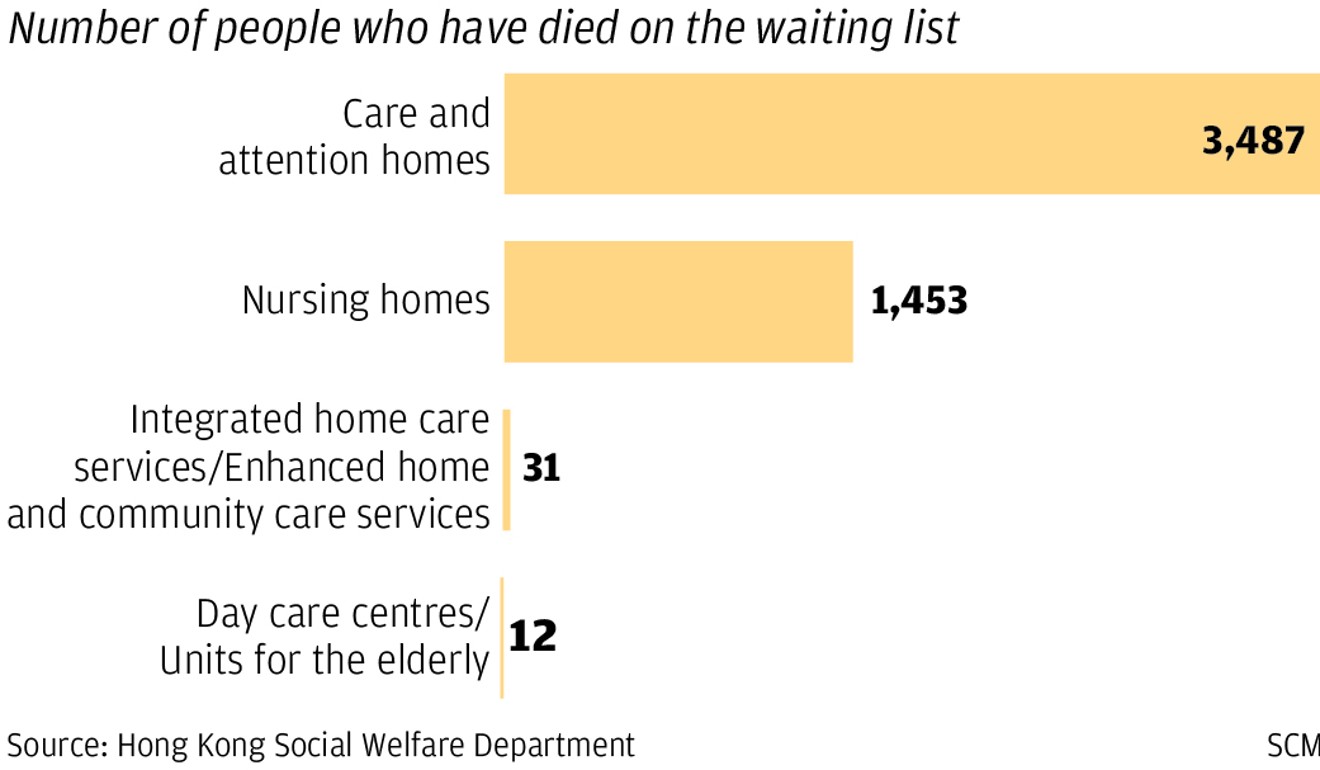

Figures from Hong Kong’s Social Welfare Department show that, in the last nine months of 2018 alone, nearly 5,000 people died while on waiting lists for places in old people’s homes or community care.

Of the total, some 3,487 were waiting for care home places and 1,453 for nursing home places.

In 2013, the department commissioned the Sau Po Centre on Ageing at the University of Hong Kong to conduct a Project on Enhancement of the Infrastructure of Long-term Care in Hong Kong.

Completed in late 2016, it recommended that the government improve the assessment mechanism, put in place in 1997, that determines what kind of services elderly people are eligible for.

“Doing nothing is not an option. The infrastructure for long-term care is not sustainable and will collapse under its own weight very quickly,” says Professor Terry Lum Yat-sang, associate director of the Sau Po Centre on Ageing.

The upgraded assessment mechanism is intended to offer a more precise appraisal of needs – for example, it will take into consideration cognitive impairment, not just functional impairment. But in the absence of a public consultation, critics and social workers worry about its implications. They also question whether merely upgrading the system addresses the root problem.

“To have old people wait in the first place is wrong and undesirable,” Lum says.

According to department figures for 2018, elderly people with moderate impairment have to wait for 38 months – more than three years – for a place in a residential care home; at the end of December 2018, some 33,385 were on the waiting list.

“The bottom line is, is it safe for old people to remain in the community?” Lum says. That is not as simple as it may sound. Many elderly people are not keen on being admitted to a nursing home, but the alternative – relying on inadequate support services – is no better.

Worried that his wife will someday no longer be able to take care of him, Chan applied for a nursing home place in 2015.

“I got offered a spot after three years of waiting. But we were still doing well. As long as conditions allow, I would still like to stay at home with my wife,” says Chan, who instead took up a social worker’s suggestion and opted for integrated home services.

He kept his place in the queue for institutional care so that, if his health should deteriorate, he would not have to reapply and start the process all over again.

However, because of staff shortages and inadequate funding, home services, which are usually subcontracted to non-governmental organisations, are also limited. Chan receives occupational therapy once a week and household cleaning services once a month.

“I asked if they could increase the frequency, but was told they do not have enough manpower,” he says.

And instead of a professional occupational therapist, often it is only a health worker. They help Chan perform the exercises, but are not qualified to assess his physical state and adjust the workout routine accordingly. Staff turnover is so high that in the space of a year Chan has gone through three occupational therapists and three health workers, who were responsible for keeping track of his case.

Many now worry that this kind of flexible arrangement – which allows elderly people to simultaneously queue for institutional care and integrated home services – may not be possible in the future, with the department looking into disallowing it. The prospect of this has sent shock waves through the community, and prompted concern groups and pan-democratic legislators to organise petitions.

In response to a question from the Post about whether simultaneous applications for home care and institutional care would still be considered, a spokesman for the Social Welfare Department said a review had yet to be completed and it would “continue to collect views from stakeholders”.

May Cheung Mei-yi, a registered social worker and member of the concern group, Concerning Home Care Service Alliance, fears the new assessment for elderly services will see the threshold for institutional care significantly raised, and that low-income families will have to resort to privately run care homes of dubious quality.

Elderly care homes should not be a dumping ground for all the unsolved problems in society. It is also a very expensive solution

An investigation by the city’s ombudsman in 2014 uncovered a systemic failure to protect the elderly in nursing homes. In one case, hospital doctors found pieces of cloth and diaper tapes stuffed in the rectum of a private nursing home resident who was suffering from low blood pressure.

“As social workers, our job is to formulate a long-term care plan for the elderly we serve, whose health is often deteriorating as they wait for the services. But if, because of lack of transparency, we are also unable to grasp the principles of the new assessment, how then do we explain it to the elderly?” says Cheung.

Lum hopes the new mechanism can reduce the current overreliance on institutional care. However, he says more has to be done to overhaul the system of care for the elderly. “Elderly care homes should not be a dumping ground for all the unsolved problems in society. It is also a very expensive solution,” he says.

To successfully introduce a care system that benefits the elderly, the government needs to spend generously on community services, without reducing – and preferably increasing – spending on old people’s homes, he adds.

Lum also sees a need for post-acute care and rehabilitation services for elderly people who have just received hospital treatment for a major injury or illness. These are currently unavailable in public health care.

“Most of the time, elderly people have no other option but to return home after they are discharged [from hospital], even though they are entirely incapable of taking care of themselves,” says Lum.

Such services are not considered part of long-term care and should not require extensive assessment, he says.

Ideally, elderly people should not face waiting lists for care, the professor says. But doing away with waiting lists would require not just a technical upgrade to the current system, but forward-thinking policy changes.

Chan believes it is unlikely he will live to see such policies implemented, but he hopes fewer elderly people will have to suffer through their later years.

“I’m getting worse month by month. I know death is only a matter of time. But I do hope the government would be less callous and care for the elderly in Hong Kong,” he says.