Chinese food isn’t fried rice and chow mein – or is it? The stories behind Chinese-Canadian cuisine and the people who sell it

- The food may not be authentically Chinese, but it’s the only kind many Canadians have eaten – and in some places the restaurants that serve them are closing

- A writer travelled across Canada, visiting as many of them as she could, to learn the backstories of the people who run them and the origins of popular dishes

Chop suey, chow mein, egg foo yong, deep-fried lemon chicken, spring rolls, and stir-fried beef and broccoli. These are all dishes typically found on the menu of a Chinese-Canadian restaurant.

They may not be authentically Chinese, but they are culturally distinct. Vancouver-born journalist Ann Hui, 36, took an interest in the culinary curiosities after learning that many immigrant restaurants in Canada’s Chinatowns were closing down or being repurposed as non-Chinese restaurants or bars.

When Hui, a reporter for Canadian newspaper The Globe and Mail, dug deeper, she discovered there were many such restaurants across the country. In some cases, they were the only restaurant in town.

Hui wrote about her adventures in a two-part series for the national newspaper.

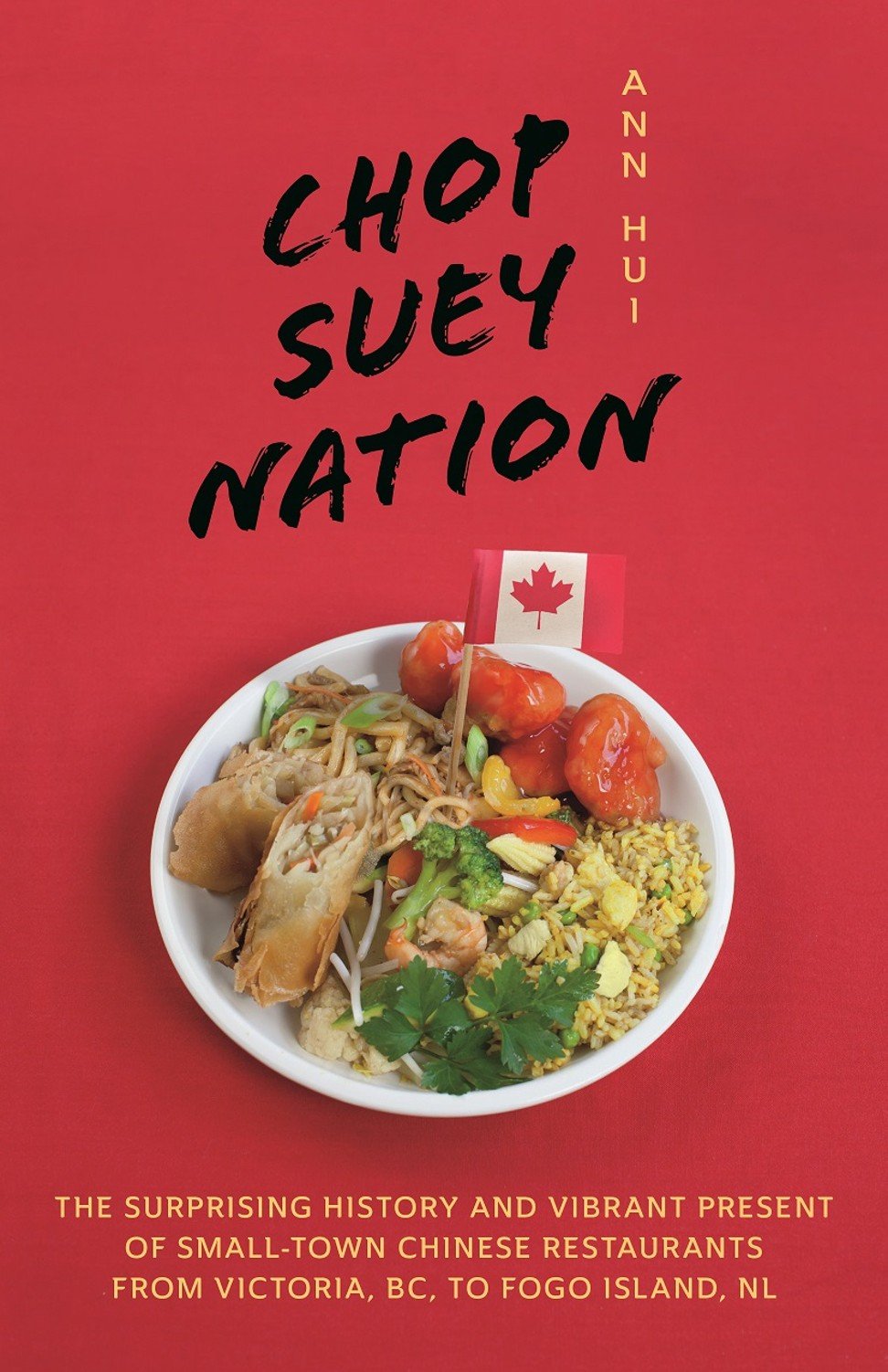

The response she received was so overwhelming that she parlayed the stories into a book called Chop Suey Nation: The Legion Cafe and Other Stories from Canada’s Chinese Restaurants, which was released early this year.

“It has really resonated with people of different backgrounds. I have been travelling a lot this past year or so – large cities and small communities,” Hui says of the feedback she had while promoting the book.

“I knew there was something very Canadian about these places. I underestimated how strongly people felt about them,” she says.

“My relatives thought it was cheaper, and was to ‘trick’ Westerners into what Chinese food was, and I internalised these feelings,” she says.

The dishes were created by immigrants from southern China who had arrived in Canada and the United States in the 1850s. Racist immigration policies dictated that the Chinese settle in ghettos called Chinatowns across North America, and many went on to open restaurants. They didn’t have all the necessary ingredients and condiments to make authentic Cantonese dishes, so they improvised with whatever was available, sometimes adjusting recipes to suit non-Chinese tastes.

On her road trip, Hui found that these restaurants were still thriving, even in the smallest towns, run by the second, third or fourth generation, or by newly arrived immigrants. To make a little extra money, they might also serve as day care centres, banks and even a temporary courthouse. As she interviewed the owners, Hui heard stories of sacrifice and perseverance.

“This island has 2,000 people and it’s incredibly isolated, and she ran the restaurant 365 days a year,” Hui recalls. “She lives alone, she’s the only Chinese woman in this place, she doesn’t speak English, her husband lives elsewhere and her children have moved away. It sounds horribly sad. But she and her husband decided if they ran two restaurants, then they could double their income and be able to put three children into university,” Hui says.

“He runs another restaurant, in Twillingate, two hours away by car and ferry. One or two of the kids have master’s degrees and they live in Halifax, Toronto and St John’s. She is filled with pride that she and her husband did it for the kids.”

On the other end of the spectrum in Stony Plain, Alberta, Hui met William Choy, the third-generation owner of Bing’s #1, who is also the town’s mayor. His grandfather opened the restaurant in 1970 and, while the decor has been updated over the years, the menu is little changed. It includes dishes such as wontons, chicken chow mein, and sweet and sour spare ribs – but also hamburgers, sandwiches and pork chops.

“William came to Canada [with his grandfather] when he was eight years old. He integrated into the community and felt comfortable and welcomed,” Hui says.

While on the road, Hui ate Chinese-Canadian food several times a day, and discovered some intriguing dishes invented in the country. One of them, in Calgary, was ginger beef, created by chef George Wong in the mid-1970s.

Thin slices of beef are coated in a thick, sweet sauce seasoned with garlic and ginger, and stir-fried so that the meat is crunchy on the outside and tender inside. In Quebec, there was fried macaroni with beef or pork and vegetables, seasoned with soy sauce and Worcestershire sauce.

Perhaps the most interesting dish Hui sampled was at Canton Restaurant in Newfoundland – chow mein made with cabbage. “The earliest Chinese cooks couldn’t get egg noodles so they used cabbage by slicing it into thin strips,” she explains. “It’s pretty tasty.”

Hui developed a new-found appreciation not only for Chinese-Canadian food, but also her own family history.

Her father had been diagnosed with cancer of the bile duct the year before she set off on her road trip, and she frequently flew from Toronto to Vancouver to be with him. Although he had never been one to blow his own trumpet, Hui knew her parents ran a restaurant called The Legion Cafe before she was born, where he prepared dishes including lasagne, hot turkey sandwiches and chicken à la king.

Visiting a few months after her articles were published, Hui tried to ask her father more about the cafe, but he grew tired of her questions.

“He got up and gave me a sheet of paper. On it were things like chicken chop suey, vegetable chop suey. The Legion Cafe had been a Chinese and Western restaurant. I was shocked,” Hui recalls. She felt foolish having written her stories and planned her road trip to ask strangers about their restaurants when she hadn’t even unearthed the truth about her own family’s business.

“My dad didn’t like to talk about himself. He would just shut down or turn on the TV,” she says. “After I showed some perseverance, he grew to be pleased that I was asking. I know he was proud his story was interesting and worth telling.”

Her father, John Hui, was born in a village called Jingweicun in Taishan, Guangdong province, while her mother, Frances Chow, was from Hong Kong. In 1974, they arrived separately in Vancouver. As new immigrants, they had to enrol in “English as a second language” classes for work co-op placement, where they ended up in the same class.

“My mum … knew English, but when she went through immigration, she was so nervous she couldn’t speak, so she was mistakenly placed in the same class as my dad,” Hui explains.

Her mother was later assigned to work as a hotel waitress, while her father was sent to cook in a restaurant in Vancouver’s Chinatown. He worked in restaurants there for two years before the couple decided to open The Legion Cafe in Abbotsford, 71km (44 miles) southeast of Vancouver.

“They heard a restaurant was for sale … so they went to check it out and then bought it,” Hui says. They stayed in Abbotsford until 1984, before moving back to Vancouver with their young family.

Hui realised her family’s story was like that of many other Chinese immigrant families who embarked on new lives running Chinese-Canadian restaurants.

“What I came to understand from taking this trip, and from speaking to people here in Canada, is that we have a story that is very distinct and unique and different from what happened in the States, and it just gave me a new appreciation … in coming here and starting these restaurants and building these new lives for themselves, it gave me a new sense of found appreciation for the food and for the cuisine that was born out of it.”