Mouthing Off | When it comes to Hong Kong and restaurants, nothing lasts forever – Viceroy and JJ’s were the in places, then Lan Kwai Fong, then SoHo. Now look at them

- Restaurant owners gravitate to neighbourhoods popular with diners, which enjoy success until landlords spoil the fun. Soon boarded up shopfronts multiply

- There’s nothing new, or surprising, about the trend – it has a relentless logic. After all, every generation wants something new to call their own

A German philosopher once said: “In fashion, one day you’re in. The next, you’re out.”

The insight of Heidi Klum on Project Runway doesn’t apply only to the fashion catwalk. It is a truism: nothing lasts forever, success is and always will be fleeting, celebrity chefs will come and go. The lucky ones manage to extend their fame for more than 15 minutes.

Thus no restaurant is guaranteed to hold three Michelin stars forever, not even the revered L’Auberge du Pont de Collonges helmed by Paul Bocuse in Lyons, France, which held the honour, bestowed in in 1965, for 55 years. This January, two years after Bocuse died, the restaurant was stripped of one of its stars.

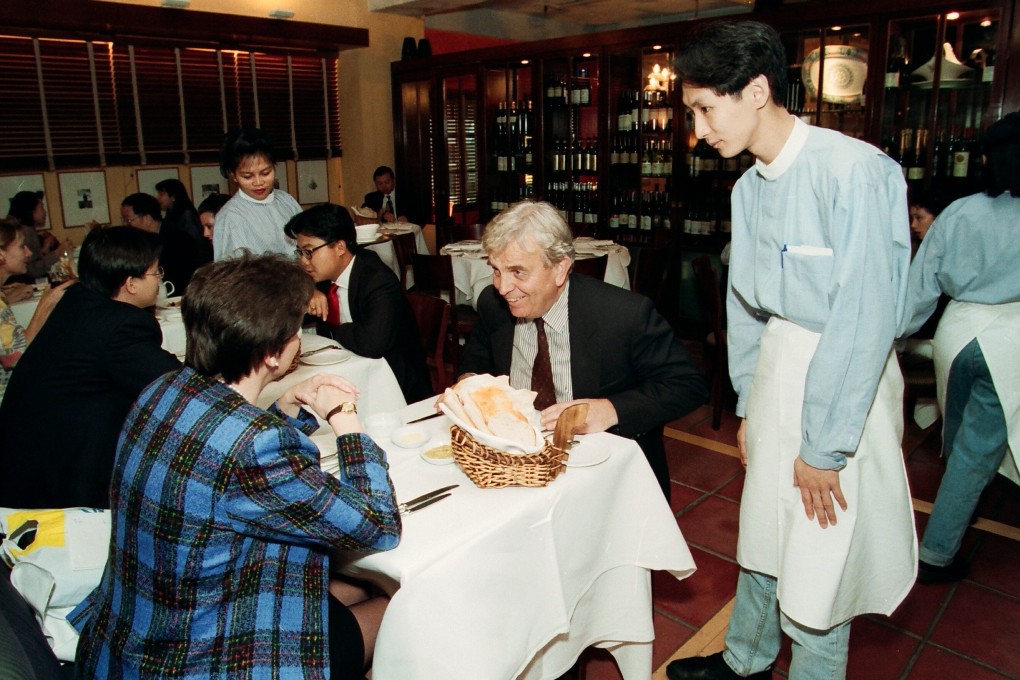

In Hong Kong, like any city with gentrifying and decaying neighbourhoods, the dining scene is constantly changing. Nightlife in the 1980s gravitated to a newly reclaimed part of Wan Chai where the Viceroy (in the Sun Hung Kai Centre) and Club JJ’s (in the Grand Hyatt) reigned.

After that, Lan Kwai Fong in Central became the place to be, as trendy people in their Versace shirts flooded into California, Indochine and Va Bene. Now the street is a sad shell of its former self. Even Chinese tourists don’t go there any more.