The story of Yeo’s: Singapore food and beverage company grew from soy sauce factory in China

- Yeo Hiap Seng started as a soy sauce factory, founded 120 years ago by two friends with the help of a church loan

- The firm, better known as Yeo’s, relocated to Singapore in 1937, survived World War II, then expanded its range to canned food, soymilk, and other drinks

As part of the celebrations to mark this year’s 120th anniversary of Yeo Hiap Seng – better known as Yeo’s – around 1.2 million cans of the brand’s popular chrysanthemum tea were distributed to residents of Singapore in National Day “fun packs”.

Although coronavirus restrictions put a stop to more gregarious festivities for Singapore’s 55th national day in August, citizens were still able to indulge in local treats – such as Yeo’s products – while watching televised celebrations.

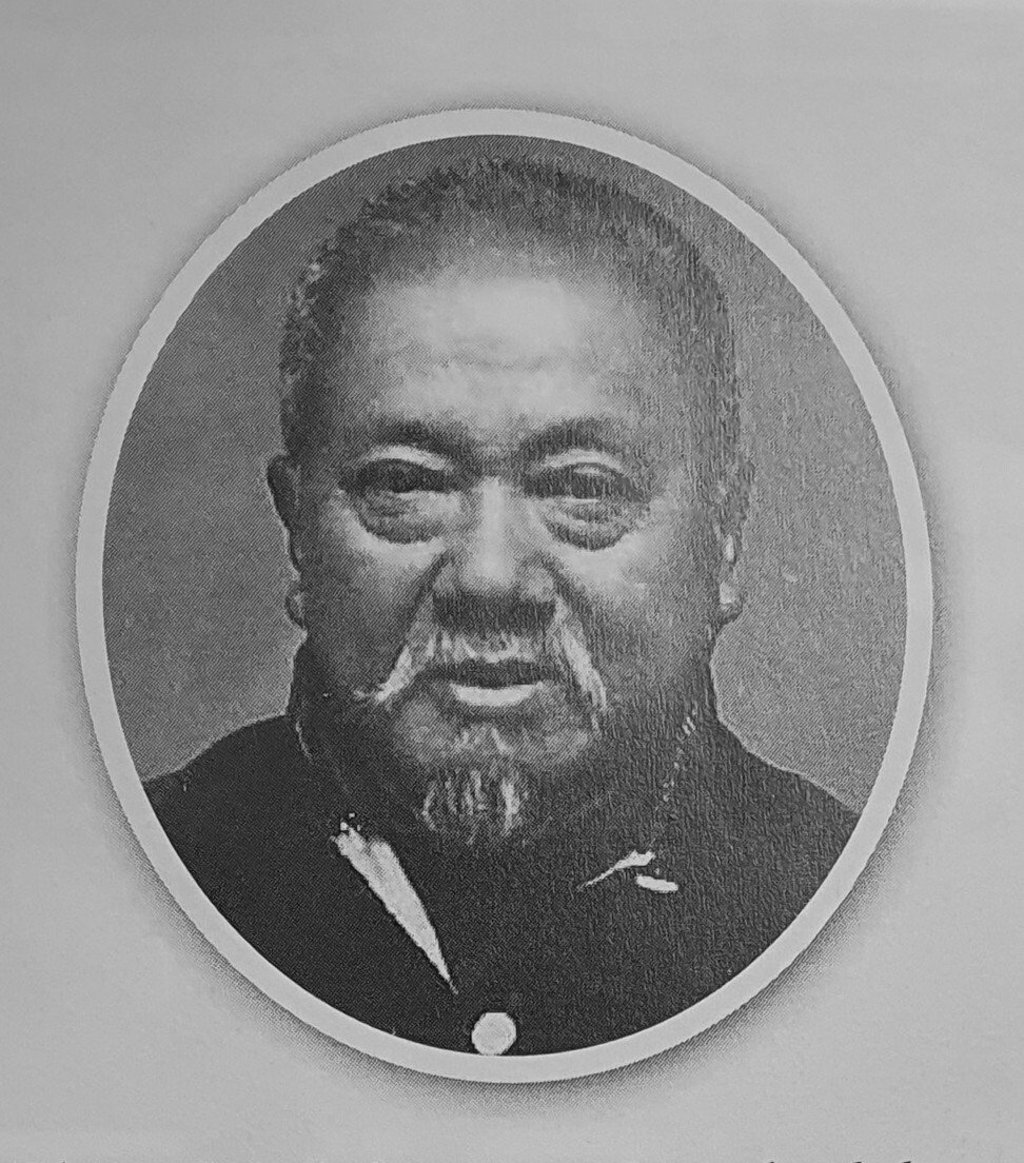

The company’s founder, Yeo Keng Lian, was born in China in 1860. When he and a friend decided to open a soy sauce factory in Zhangzhou, Fujian province, they had each saved the equivalent of US$295 to invest in their new venture, but they needed US$660. A devout Christian, Yeo prayed for a solution before going to bed.

He dreamed he was lost in a raging sea, but someone threw him a plank that turned into a bridge and brought him to dry land. When he awoke, he confidently approached his church’s pastor for a loan and immediately received the cash that he needed.

In 1901, the two friends founded the Hiap Seng Sauce Factory, which was renamed Yeo Hiap Seng Sauce Factory after the friend pulled out of the business two years later. While “Yeo” was Keng Lian’s family name, “hiap” was chosen because, when written in Chinese, it has a cross character – symbolising Christ – and three copies of the Chinese character for strength. Finally, “seng” means “success”.

Christian values were important in Yeo Hiap Seng – company meetings started with prayers and hymns, employee welfare was prioritised, and good hospitality was emphasised.