Why Hong Kong researchers are studying poo’s potential to save lives

Transplanting faeces to recolonise a patient’s gut with healthy bacteria has recently kindled the interest of scientists for its potential to treat infections and chronic conditions; Chinese doctors were doing it 1,700 years ago

It may sound far-fetched, but one day human faeces might be the cure for illnesses ranging from life-threatening gut infections to chronic conditions such as obesity and diabetes.

Transplanting faecal matter from one person to another to recolonise the gut with healthy bacteria – known as faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) – has garnered a lot of interest from scientists around the world in recent years, according to a report published in the journal PLOS Biology on July 12.

“There is no doubt that poo can save lives,” says the report’s corresponding author Seth Bordenstein, an associate professor of biological sciences and pathology, microbiology, and immunology at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, in the US state of Tennessee.

Faecal transplants have a long history in Chinese medicine. An early application in humans was recorded in the fourth century by a Chinese doctor named Ge Hong, who noted prompt recovery from diarrhoea in many patients following faecal transfer. In the 16th century, the therapy was popular enough to get the nickname “yellow soup”.

During the second world war, German soldiers from the Afrika Corps consumed camel droppings to help them recover from bacillary dysentery when no antibiotics were available.

The subject attracted little interest from Western scientific circles until 2010, Bordenstein notes, with fewer than 10 articles on the subject appearing per year in PubMed, an index of biomedical literature. From 2011, the number began rising exponentially, with more than 200 papers on faecal transplants appearing in 2015, a trend that shows no sign of easing.

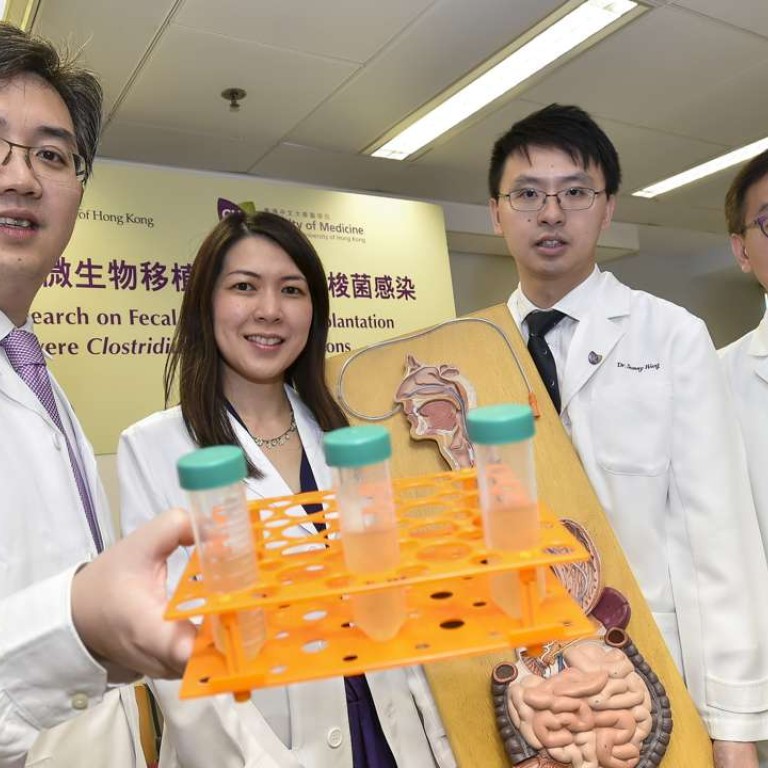

Since the start of 2015, researchers at the Chinese University of Hong Kong have been studying the effectiveness of using FMT to treat patients infected with Clostridium difficile, a bacteria that causes infectious diarrhoea – a problem which often occurs following antibiotic treatment. More than 30 patients have been treated so far, with a success rate of 80 to 90 per cent, according to Ng Siew-chien, associate professor in the university’s department of medicine and therapeutics.

Anticipating a rapid need for the therapy in future, university researchers are developing a donor stool bank to facilitate delivery of intestinal transplants. The goal is to recruit 10 lean healthy donors who are able to attend regular screenings and donate frequently.

Ng said: “There will be a very stringent screening protocol. Such strict criteria are necessary to maintain the safety of subjects who receive the infusion. Our donor stool bank will also be accompanied by short- and long-term safety [assessments].”

Apart from C. difficile infection, Ng says her team is also studying the use of FMT for irritable bowel syndrome, ulcerative colitis and obesity with diabetes, and has performed the therapy in a patient with antibiotic-associated diarrhoea.

Bordenstein, who reviewed the growing scientific literature on FMT in his report, says research into the subject is just getting started. “It is driven by the new paradigm of the microbiome which recognises that every plant and animal species harbours a collection of microbes that have significant and previously unrecognised effects on their host health, evolution and behaviour,” he says.

VICE correspondent Thomas Morton reports from the labs and lavatories where this medical revolution is taking place.

In recent years, faecal transplants are increasingly being used as the treatment of last resort for certain infections in the human gut. In particular, there has been remarkable success in treating the nursing home and hospital-acquired scourge, C. difficile, which can cause life-threatening inflammation of the colon.

The incidence of C. difficile infection has increased in recent years, Chinese University researchers say. From 2009 to 2013, the incidence of C. difficile infection at Prince of Wales Hospital increased about threefold. There are new cases every one to two days, adding up to an average of 15 to 20 cases every month.

FMT has an 80 per cent to 95 per cent cure rate for C. difficile infections – significantly higher than the 20 per cent to 25 per cent success rate of conventional antibiotic treatment. There is also preliminary evidence FMT can be effective in treating multiple sclerosis and Crohn’s disease.

The procedure for FMT involves the collection of 50 to 100 grams of stool from a healthy donor, followed by dilution with a sterile saline solution and filtration. The liquidised stool is then infused into patients, usually through colonoscopy. The university’s centre for digestive health offers the service for HK$10,000 to HK$15,000.

For a more straightforward method, a biotech start-up based in the US state of Massachusetts has developed FMT in pill form. OpenBiome’s capsules contain carefully screened, freeze-dried donor stool that patients swallow to get, reportedly, nearly the same benefits.

Some people even try do-it-yourself faecal transplants at home. A growing number have taken to blogs and social media sites such as YouTube and Facebook to share advice and techniques for at-home procedures, according to a WebMD article in December 2015.

The website ThePowerOfPoop.com details a step-by-step procedure for do-it-yourself FMT.

Basically, donor stool is mixed with a saline solution in a smoothie blender and the solution is then squirted into the rectum with an enema bottle or bag.

There is emerging evidence of a possible role of FMT in diseases such as irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, obesity, diabetes mellitus, autism, depression, Parkinson’s and several others

Ng cautions against the use of do-it-yourself FMT, saying that although the practice is increasing in the West, it may not be safe, as cases of weight gain and bowel disease have been reported following self-treatment. “Even people with good health may still carry certain germs that can be silently transmitted to others via faecal transplant if vigilant donor screening is not performed. The longer-term effects of FMT also need to be monitored closely.”

No serious adverse effects have been noted among patients who have undergone the procedure at Chinese University, Ng says. “Some individuals may have had symptoms of abdominal discomfort, bloating or diarrhoea on the day of infusion, [but this was] resolved in one to two days,” says Ng.

In a recent article on ETHealthWorld.com, Dr Avnish Seth, director of gastroenterology and hepatobiliary sciences at Fortis Memorial Research Institute in India, notes that no significant short-term adverse effects of FMT have been reported in world literature.

“FMT has the potential to become a low-cost, readily accessible and safe treatment option for patients with diseases of the intestine such as ulcerative colitis. There is emerging evidence of a possible role of FMT in diseases such as irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, obesity, diabetes mellitus, autism, depression, Parkinson’s and several others. However, until more robust data is available, FMT should be performed only as a part of approved clinical trials.”

Bacteria are the most abundant active agent in stools, with healthy human stools containing on average 100 billion bacteria per gram, Bordenstein says. But there may be other biological and chemical entities in stools that are causing or assisting the effects of FMT, he adds.

Stools also contain 100 million viruses and archaea per gram. (Archaea are a little studied domain of single-celled organisms that were classed as bacteria until the 1970s.) There are also about 10 million colonocytes (human epithelial cells that help protect the colon) and a million yeasts and other single-celled fungi per gram.

Most research has focused on the bacterial component of stools, but Bordenstein says it is possible the effects of FMT may be influenced by, or possibly even caused by, their non-bacterial constituents. As a result, he has called for increased research to separate the effects and interactions of each of these components.

“When scientists identify the specific cocktails that produce the positive outcomes, then they can synthesise or grow them and put them in a pill,” he says. “That will go a long way to reducing the ‘icky factor’ that could slow public acceptance of this new form of treatment.”