Two surprising health benefits of the pill, unrelated to birth control, discovered

Progesterone, found in most forms of hormone-based birth control, shows promise in reducing inflammation and promoting faster lung repair

Being on the pill might provide you more protection than just against pregnancy. The female sex hormone progesterone – contained in most forms of hormone-based birth control – has shown in a new study on mice to stave off the worst effects of influenza infection and help damaged lung cells to heal more quickly.

Researchers from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, reporting their findings in the journal PLOS Pathogens, suggest that sex hormones have an effect far beyond the reproductive system and that progesterone may one day be a viable flu treatment for women.

In the study, some female mice received progesterone implants while others didn’t. The mice were then infected with influenza A virus. Both sets of mice became ill, but those which had the implants had less pulmonary inflammation, better lung function and saw the damage to their lung cells repaired more quickly.

Progesterone was found to be protective against the more serious effects of the flu by increasing the production of a protein called amphiregulin by the cells lining the lungs. When the researchers bred mice that were depleted of amphiregulin, the protective effects of progesterone disappeared as well.

Study leader Sabra Klein, an associate professor in the school’s department of molecular microbiology and immunology, says there is no scientific data to date showing whether progesterone in humans has any relationship to flu severity. To understand this link better, Klein says Johns Hopkins colleagues doing flu surveillance in humans have added questions about specific forms of birth control to their questionnaires.

Klein and colleagues are now studying the precise mechanism for how progesterone increases the concentration of amphiregulin in the lungs. Women of reproductive age are twice as likely as men to suffer from complications related to the influenza virus.

Klein says: “We really want to understand from a therapeutic sense how this could potentially work in humans to keep women from experiencing complications from the flu.”

Eating your greens could enhance sports performance

Cartoon character Popeye scoffs spinach to gain extra strength – and a new study suggests athletes should do the same too. Supplementing one’s diet with nitrate – commonly found in leafy greens such as spinach – in conjunction with sprint interval training in low-oxygen conditions could enhance sports performance, according to research from the University of Leuven in Belgium.

The study, published in Frontiers in Physiology, involved 27 moderately trained participants. They were given nitrate supplements before each short but intense cycling sessions – held three times a week. To assess differences in performance in different conditions, the study included workouts in normal oxygen conditions and in low-oxygen (hypoxia) conditions such as those found in high altitudes.

After only five weeks, the muscle fibre composition changed with the enhanced nitrate intake when training in low-oxygen conditions.

“Whether this increase in fast-oxidative muscle fibres eventually can also enhance exercise performance remains to be established,” says Professor Peter Hespel from the Athletic Performance Centre at the University of Leuven.

He cautions that consistent nitrate intake in conjunction with training must not be recommended until the safety of chronic high-dose nitrate intake in humans has been clearly demonstrated.

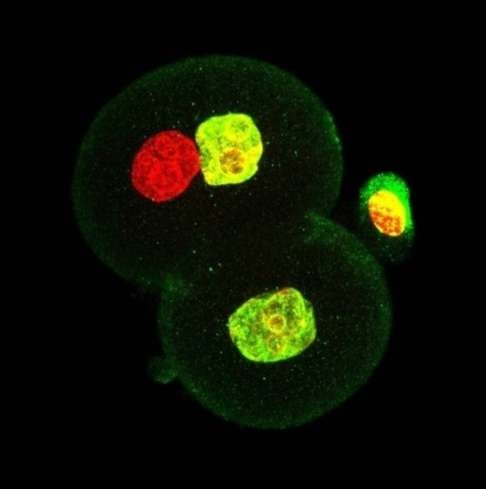

Scientists make embryos from non-egg cells

Scientists have shown for the first time that embryos can be made from non-egg cells, a discovery that challenges two centuries of received wisdom. At the department of biology and biochemistry at the University of Bath in Britain, eggs were “tricked” into developing into an embryo without fertilisation, resulting in embryos called parthenogenotes. The researchers then developed a method of injecting mouse parthenogenotes with sperm that allows them to become healthy baby mice with a success rate of up to 24 per cent.

“It had been thought that only an egg cell was capable of reprogramming sperm to allow embryonic development to take place,” says molecular embryologist Dr Tony Perry, senior author of the study that appears in the journal Nature Communications. “Our work challenges the dogma, held since early embryologists first observed mammalian eggs in about 1827 and observed fertilisation 50 years later, that only an egg cell fertilised with a sperm cell can result in a live mammalian birth.”

The baby mice born as a result of the technique seem completely healthy, but their DNA started out with different epigenetic marks compared with normal fertilisation. This suggests that different epigenetic pathways can lead to the same developmental destination, something not previously shown.

The discovery has ethical implications for recent suggestions that human parthenogenotes could be used as a source of embryonic stem cells because they were considered non-viable. It also hints that in the long-term future it could be possible to breed animals using non-egg cells and sperm. It could have potential future applications in human fertility treatment and for breeding endangered species.