Two big myths about breast cancer – and what Hong Kong women really need to know

Misconceptions still surround the disease, that prevent the city’s women taking the illness seriously and getting screened regularly for it

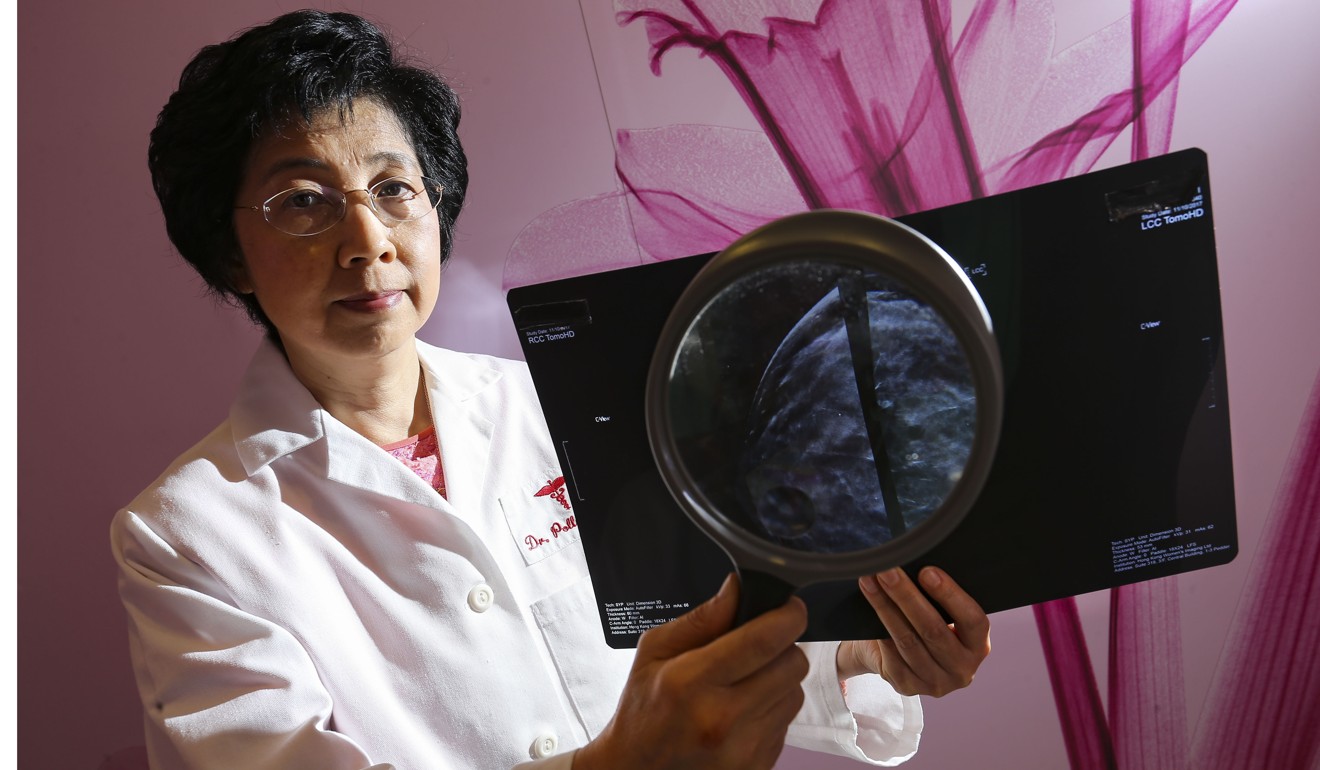

A top expert in breast cancer is urging Hong Kong women to shake off their misguided belief that they will not develop the disease – the most common cancer for women here and the third leading cause of cancer deaths in women – and to have their breasts checked.

Invasive breast cancer is an aggressive type that spreads into the lymphatic system and bloodstream, and other organs.

Cheung says the causes behind the rising rate are varied, but a major culprit is a more Westernised urban lifestyle. City dwellers exercise less, tend to consume meat and high-fat dairy diets, and are exposed to higher pollution and carcinogen levels.

However, Cheung cites two common misconceptions that prevent many Hong Kong women from taking breast cancer seriously and getting screened.

Myth 1 Having no family history of breast cancer means you will not develop the disease.

Genetic testing is a huge trend worldwide and Hong Kong is no exception, as high-profile endorsers encourage women to get screened for BRCA 1 or 2 gene mutations. Those with the gene mutation(s) have an unusually high risk of breast and ovarian cancers.

Pre-op chemotherapy could help cancer patients keep their breasts, report by Hong Kong support group shows

A downside to this is that people believe genetics eclipse any other factor as determinants of breast cancer. Cheung says patients routinely ask if they will pass the disease on to their children, while others deny they will develop the disease as there is no family history of it.

Breast Cancer Registry statistics give a clear picture. “Over 90 per cent of all (people with) breast cancer in the city do not have immediate family members with the disease,” Cheung says, “and only 10 per cent of women with breast cancer have immediate family members, such as siblings or parents, with breast cancer.”

Second-generation Chinese women whose mothers emigrated to America experience the same incidence of breast cancer as their Western counterparts, she notes, adding “this negates the factor of genetic transmission”.

She is concerned that many women without a family history of the disease shrug off the risk – and do not get checked. The belief that “since they have no history, they will be immune to this disease – that’s wrong,” she warns.

Statistically, one in every 17 women in Hong Kong gets breast cancer in her lifetime.

Myth 2 Smaller breasted women have a lower risk of breast cancer.

Size does not matter when it comes to breast cancer. Breast Cancer Registry statistics show slightly more than half of all breast cancer patients diagnosed in Hong Kong have B cup or smaller sized chests. It’s true that most Asian women have denser breasts than Western women, but that only means it will be more difficult to feel or find a tumour mass during tests, Cheung says.

“Women with small breasts can have cancer,” she says. They can benefit from screening, mammograms, and ultrasound screening.

Growing numbers of young women are developing breast cancer.

This startling trend is observed in many places worldwide, not only in Hong Kong. Cheung attributes the phenomenon to many factors, including a Westernised diet, and women’s greater exposure to carcinogens in modern times, from sources including urban pollution and the chemicals in beauty products.

New mothers can lower their risk of getting this disease by breastfeeding their babies, Cheung says. Milk formula was all the rage for the previous generation, but that trend has changed, thanks to more awareness of the health benefits of breastfeeding – for both mums and infants. “The lactating process has protecting factors against breast cancer,” she says.

In women there are several breast-change phases from puberty to pregnancy. During the latter period, breast cells mature, a process that cuts mothers’ chances of breast cancer. Lactating mothers undergo cellular changes that result in the release of cells including those containing immunoglobulin, which has protective effects against breast cell change.

How one breast cancer survivor turned despair into determination to help other Hong Kong women

Research shows breastfeeding for at least six months will be the most protective benefit, advises Cheung, a recommendation in line with the World Health Organisation. She adds that breastfeeding beyond six months is even better, but that those who cannot should not worry. “Even if you are breast feeding for a month, this lactation change of your breast cells will give you a protective effect against breast cancer,” she says.

Much evidence supports such claims. In 2015, a US study led by Marilyn Kwan published in the Journal of National Cancer Institute looked at 1,636 cases and found, after a nine-year follow up, those that breastfed had a 30 per cent lower risk of breast cancer reoccurrence and a 28 per cent lower risk of death from this disease.

The single most important step any woman can take is to check her breasts regularly. About 60 per cent of breast cancer cases are in women aged 40 to 59, so Dr Cheung urges those aged 40 and above in particular to get their breasts checked and be aware of any unusual breast changes, be it a lump, nipple discharge or nipple retraction. After 40, see a doctor once every two years to have a breast screening with a mammogram. Premenopausal women with denser breasts should add an ultra-sound screening to their check-ups. Tumours found through screenings are 40 per cent smaller than the ones found by patients.

Hong Kong’s 15,000 cases of breast cancer complication made worse by lack of awareness

Hong Kong has no government-driven screening programme even though breast carcinoma in Hong Kong today affects one in 17 women compared to one in 21 in 2008. Cheung says this is problematic as the pattern in Hong Kong is to discover cancer when it has reached stage two while places that have regular screenings usually detect it when it is still at stage one.

Only about 10 per cent of cases in Hong Kong are detected through screening while 80 per cent are detected accidentally.

Cheung cites the UK, where breast-screening programmes are part of the National Health Service, so all women at a certain age are urged repeatedly to get their breasts checked. In Taiwan, a free mammogram service for women was rolled out in 2013.

In a statement, the Department of Health said its Cancer Coordinating Committee’s Cancer Expert Working Group on Cancer Prevention and Screening said it “considers that there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against population-based MMG [mammography] screening for asymptomatic women at average risk in Hong Kong.”

The department’s statement also said: “Recent studies in some overseas countries (even among those with much higher cancer prevalence) showed that harms such as false positives, false negatives, overdiagnosis, overtreatment and potential complications arising from subsequent invasive investigations or treatment may outweigh benefits.” It cited the 2013 Cochrane Review which estimated that mammography screening resulted in a 15 per cent decrease in breast cancer mortality – and a 30 per cent increase in overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

Hope in a hobby: ‘Dreams Come True’ programme for Hong Kong breast cancer patients inspires

Women with limited means who have concerns about their breast health may qualify for free breast screening through the Hong Kong Breast Cancer Fund’s Breast Health Centre, that may refer them to a public or private hospital. Visit hkbcf.org for details, as well as a list of where to go for a mammogram.