The microbiome explained: how a vast army of gut bacteria regulates body’s functioning

- When we eat, we feed the bacteria in our digestive system, and they produce substances both beneficial and harmful

- New research supports the idea that microorganisms in the gut play a role in all sorts of diseases and health conditions

Microbiome. You’re hearing the word a lot now, right. But what does it mean?

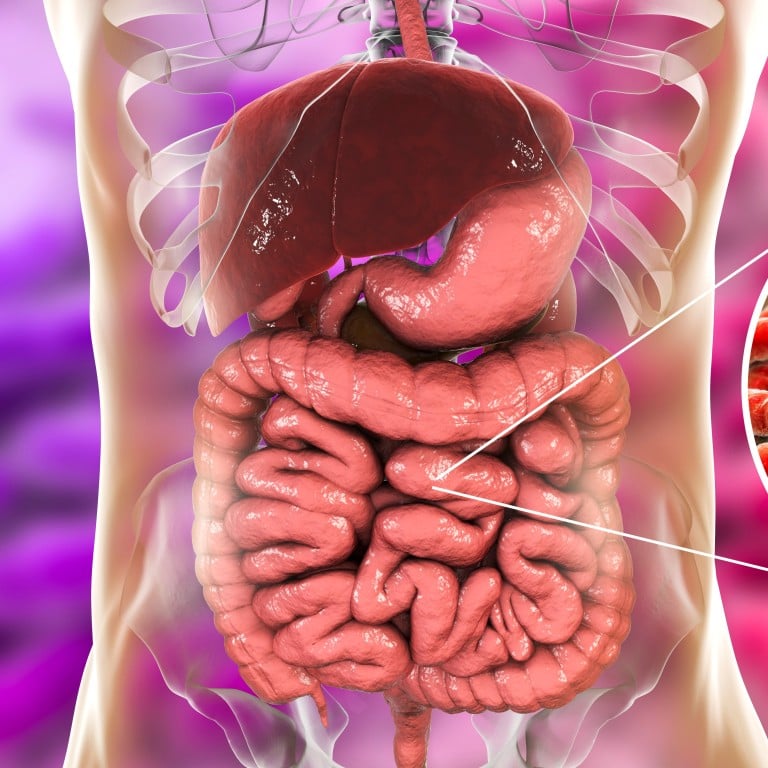

Dr Paul Ng, a Hong Kong based specialist in gastroenterology and hepatology, says the microbiome, or microbiota, refers to the myriad microorganisms living inside the human gut, mainly in the colon.

“It’s not a new discovery. For decades, doctors had thought that there are strains of bacteria living parasitically in the colon. But we actually need these bacteria to function properly,” Ng says.

While the knowledge of the microbiome isn’t new, our understanding of how we interact with the microbiome is.

The human microbiota, University of Colorado research associate Maggie Stanislawski explains, “is the community of microorganisms (bacteria, viruses and fungi) that live in and on the human body, and the microbiome includes these microorganisms’ genomes and their interactions with the environment”.

To explain the importance of the microbiome, Ng uses an analogy from the animal world. “Rabbits need the bacteria in their digestive systems to digest grass. Without the bacteria they die of starvation even if they’re eating grass. It’s a question of simple symbiosis,” he says.

The relationship between humans and bacteria is much more complicated, however. “We feed the bacteria as we eat,” says Ng. “The bacteria in turn churn out stuff that is both wanted and unwanted in our gut. Different strains produce different stuff. Some can be beneficial, for example vitamin K.

“Some can be harmful, like toxins which irritate the gut, causing diarrhoea and inflammation and bleeding. As long as the strains of bacteria stay in ‘balance’, they counter-check each other, so that none of the strains overgrow and cause problems.”

It’s when that equilibrium is disrupted that things go wrong, he says. When the balance is upset in the gut it can affect our body weight, hormone levels, sensitivity of the gut to pain, and cause inflammation. “Doctors and researchers are beginning to understand that the effects go well beyond the confines of the gut,” he says.

Stanislawski, whose work is focused on the gut microbiota of infants and their mothers in relation to obesity, says that different areas of the body host characteristic microbiota. There are more microbial cells in your body than your own cells, and cumulatively they weigh 1.4 to 2.3kg.

The types of microbiota that inhabit the gut are different from those in the mouth or nose, she says. She agrees with Ng that increasingly the human microbiome is studied in relation to health or disease, and adds: “There’s a growing body of research supporting the idea that these microorganisms [particularly in the gut] play a role in all sorts of diseases, and even mental health problems.”

There are many reasons for the interest in the microbiota, she says, including the potential for health promotion, disease prevention, and disease treatment.

It’s not a new discovery. For decades, doctors had thought that there are strains of bacteria living parasitically in the colon. But we actually need these bacteria to function properly

Managing our gut environment to support friendly microbiota is, increasingly, recognised as key to good health. A study by the University of Alabama suggests that a high-calorie, high-fat diet combined with age could upset the microbiome balance and lead to inflammation and heart failure. Antibiotic overuse is a known cause of microbiome upset too, killing off good bacteria and upsetting that crucial balance.

So what can we do as individuals to cultivate good gut bacteria? Questioning an antibiotic prescription is one place to start. Ask your doctor whether it is necessary.

Sometimes, having a caesarean section and using baby milk formula are necessary, but if there is a choice, women should opt for vaginal delivery and breastfeeding; a newborn’s microbes are compromised when they are delivered via C-section or fed formula. One generation hands over their microbiome to the next.

As Stanislawski explains: “Maternal gut microbiota is important because mothers pass on their gut microbiota to their infant in various ways (direct transfer, potentially in breast milk), and her gut microbiota may also influence the development of the metabolic and immune systems of the fetus during gestation – utero programming.”

Babies born via C-section or fed formula miss out on that transfer and need to play catch-up.

Lastly, skip antibacterial soaps and hand gels, and wash your hands with plain old soap and water instead. There’s no proven benefit to antibacterial soaps.

A little bit of clean dirt is no bad thing.