The real meaning of dreams: new science on how our brains work, including why dreaming is like art

- Long-held Freudian beliefs about dreams are now being challenged by a new group – neuroscientists who are involved in sleep research

- Some say dreams have no meaning at all; others believe they offer the dreamer a different perspective on themselves, like a piece of art

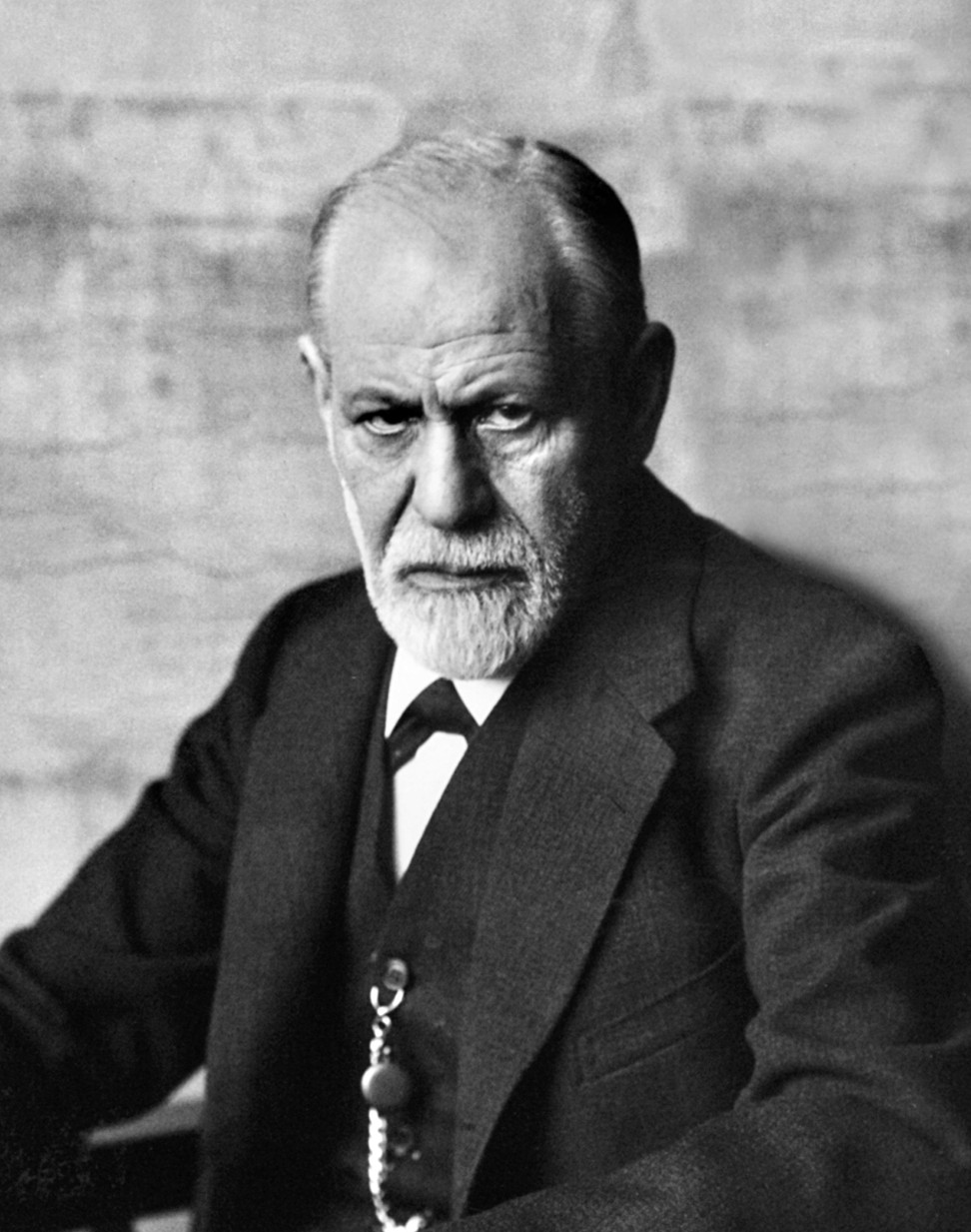

When a psychologist analyses a dream you’ve told them, they are using psychoanalytical techniques that have their foundation in those developed by Sigmund Freud at the close of the 19th century.

According to Freud, dreams are representations of events or desires that occurred in childhood – usually related to sexuality or sexual development – that are unacceptable to our conscious minds, and therefore repressed or denied during our waking state. When we sleep, these events are made manifest in our dreams, in a distorted fashion that disguises their true nature from us, Freud said.

Freud also believed that if a psychologist can reveal the concealed meaning of the dream – the event or desire that it represents – to a patient through psychoanalytic techniques, what the patient discovers can aid recovery from mental illness.

Freud’s conclusions have long been disputed because they are unscientific – he conducted very few experiments to back up his claims, and mainly formed his theories by studying his own dreams. It is also impossible to prove his theories true or false, something that is necessary if something is to be described as scientific. But even so, his methods, or variations of them, are still in use, because they sometimes do have a beneficial effect on patients with mental health problems.

Now Freud’s theories about dreams are being challenged by another group – neuroscientists who are involved in sleep research.

Neuroscience is brain science, the study of the physical brain. Although science has a long way to go before it can define what human consciousness is, neuroscientists believe that consciousness is contained within the brain, not the mind.

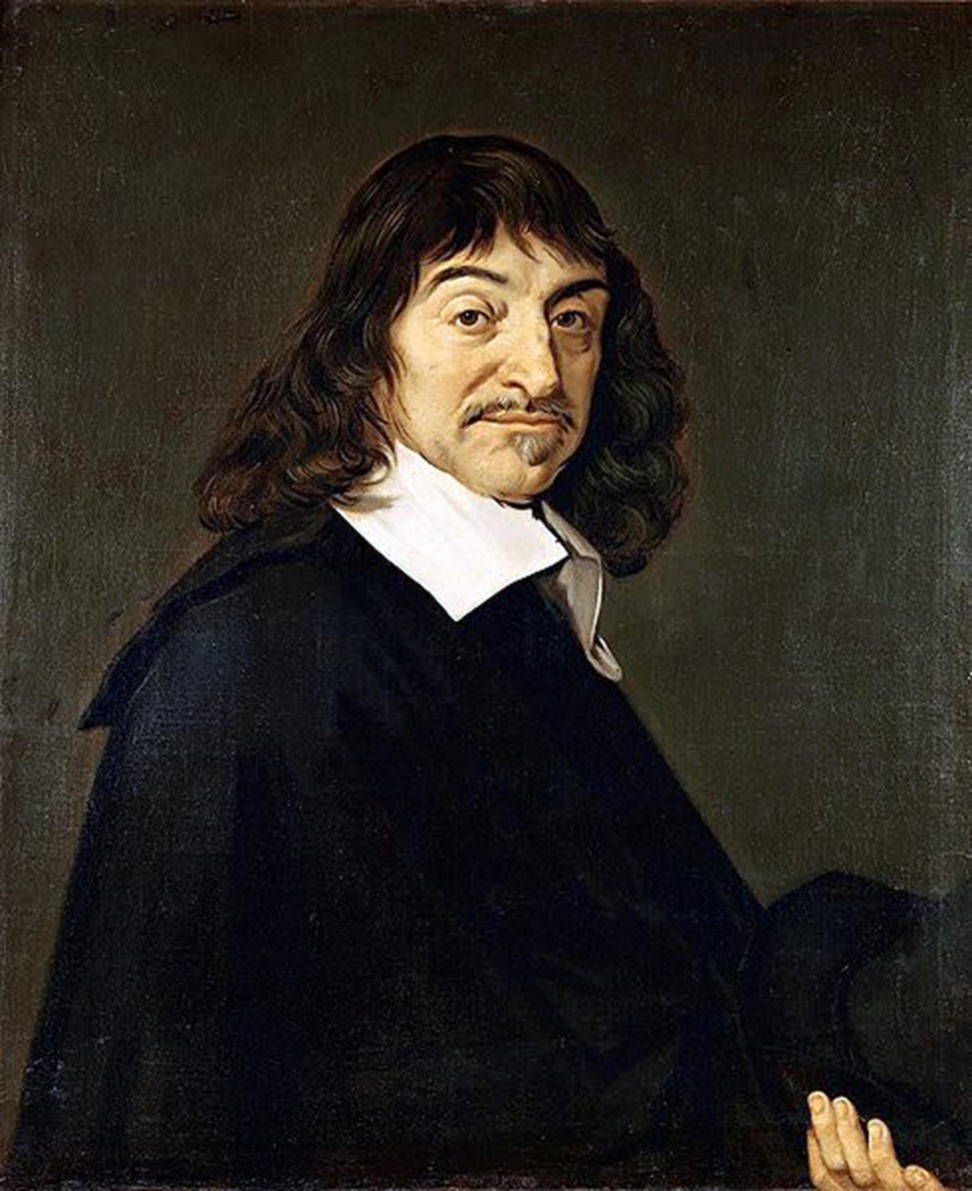

Ever since philosopher Rene Descartes (1596-1650) developed the theory that later became described as “Cartesian Dualism”, most cultures have believed that we have a mind that is separate from the brain. Those who are religious believe in a disembodied soul that is separate from the brain, and even those who are not religious usually think that our mind is a different entity to our brain.

Neuroscientists say that Cartesian Dualism is false. There is no mind, only the brain, and consciousness lives within the organ itself. Consciousness is part of the physical part of us – it does not exist in a disembodied form.

Some neuroscientists go as far as to say that consciousness is an illusion created by our brain processes so that we can effectively cope with the outside world, a world which may exist in a form that is actually much different in nature to the way we experience it.

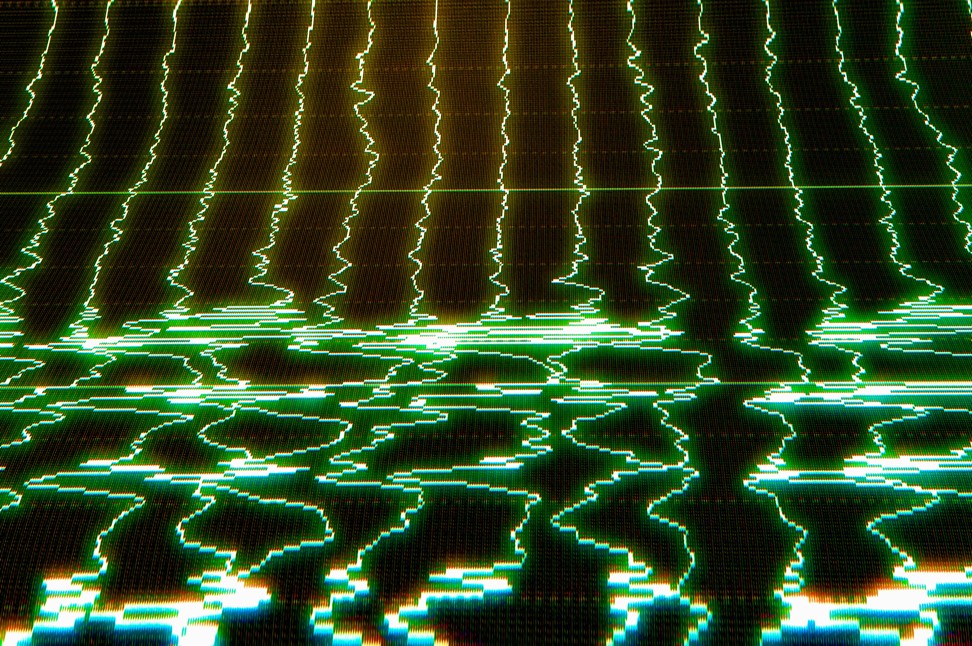

Neuroscientists believe that dreams are generated by the brain processes – the chemical processes – that take place while we are asleep.

“It turns out that most dreaming occurs under the calm cover of sleep and is a result of a built-in mechanism of brain activation that operates in all of us every night of our lives,” says Allan Hobson, professor of psychiatry emeritus at Harvard Medical School in the US and a pioneer of sleep research.

Your brain does not switch off when you go to sleep as is commonly thought, Hobson says – just the opposite. Neuroscientists have proved that there is much brain activity during sleep by using equipment such as fMRI, or functional magnetic resonance imaging – scans that measure and map the brain’s activity, identifying active areas of the brain. During sleep, the brain reorders our memories in the way it decides they will be most useful to us, for instance.

“The brain is just as active during sleep as it is during our waking hours,” Hobson says. “The difference is that the chemistry has changed. Your input and output are blocked, you can’t move, and your reaction to sensory stimulation is decreased. Your memory system is not active. But your brain is still active.”

What you dream about can show you who you are. Dreams can allow you to see aspects of your life that you would not otherwise see, in the same way a work of art offers new perspectives to the viewer

Neuroscientists say that dreams arise as a result of this activity. Some say that dreams are not meaningful at all, claiming that they are just inconsequential by-products of our night-time brain activity. But Hobson, who has kept a dream diary for years, thinks that there is meaning to be found in our dreams.

Dreams are not caused by Freudian concepts like repression, denial and displacement, he says. But the fact that dreams are produced by physical brain processes doesn’t mean they can’t tell us something about ourselves, he notes.

“Dreams are meaningful, they always have been, and they always will be,” Hobson says, adding that the content of a dream is not disguised in the way that Freud claimed it was. (He does, however, say that Freud was right about some issues, and that he is “picking up from where Freud left off in 1895”.)

“Dreaming is actually designed to reveal meaning, not to obscure it – dreams are not there to conceal the emotional meaning from the dreamer. I find my own dreams remarkably frank,” he says.

The process is a bit like updating your personal software every night. Our perception of the world is based on a huge amount of information and data collected during the waking hours, and the brain must weed out the useful bits from the flotsam and jetsam.

“While dreaming, the brain tries to make sense of all the data it has collected,” Hobson says, explaining that the brain continually adapts our view of the outside world so that it can make better decisions which increase our chances of survival. “You have a world view and I have a world view. Every night we change that world view slightly but significantly, depending on what happens during the day. That is an important function of dreaming.”

Hobson says that although the act of dreaming is important, it is not necessary for us to analyse our dreams, or even be aware of them. They will do their work regardless of whether we take notice of them or not, and it’s fine to simply forget about them.

But if we do choose to look at them, and keep a dream diary, we can learn something new about ourselves.

The unique nature of dreams – “vivid, bizarre, emotional, unreasonable, hard to remember”, as Hobson puts it – works in the same way as a piece of art, offering the dreamer a different perspective on themselves.

“What you dream about can show you who you are,” Hobson says. “Dreams can allow you to see aspects of your life that you would not otherwise see, in the same way a work of art offers new perspectives to the viewer. Dreaming is a kind of art form.”