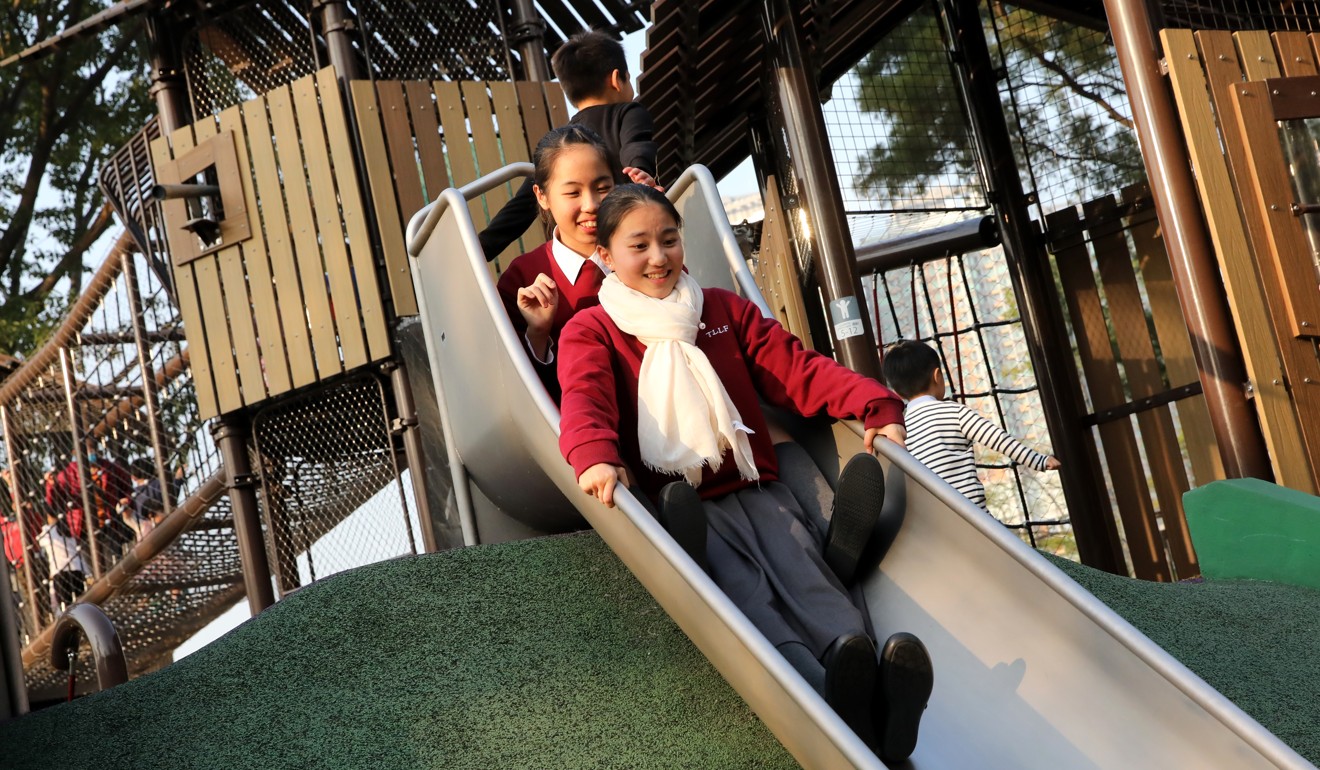

Hong Kong’s first inclusive playground helps children with special needs feel welcome

- The barrier-free playground encourages children of all abilities to play together in a safe, exciting environment

- It should help erase the stigma around special needs, although a recent survey shows many users of the playground lack awareness about inclusion

Hong Kong’s first inclusive playground for children with special needs has been given the thumbs up, according to a survey of users. The facility is a step towards stamping out the stigma facing such children, says the organisation which carried out the survey.

The city government’s Architectural Services Department designed the playground, which is about the size of a soccer pitch, and the Leisure and Cultural Services Department runs it.

The park is all about engaging the senses, with an interactive water zone, sand area and music zone featuring built-in musical instruments.

“Inclusion allows children with special needs to live, play, and learn alongside their non-special-needs peers, rather than being segregated,” says Beyond’s chief executive, Janet Pau Tong.

“A big part is recognising the sense of worth in children with different abilities and challenges, and to respect them and their families.”

Pau says the survey highlights the need for greater public awareness about children with special needs.

“The personal experiences of many families of children with additional needs and different abilities in Hong Kong suggest that public awareness and understanding of special needs is still inadequate.

“Children still face overt or subtle discrimination and stereotyping, making it difficult for these families to truly experience an inclusive community.”

Pau, who has a bachelor’s degree in psychology and international studies from Yale University and a master’s degree in public policy from Harvard University, says playgrounds like the one at Tuen Mun Park are vital for children with physical needs who require adaptive and accessible equipment, and for those who may have sensory needs or experience anxiety socialising.

She notes that the new facility has “playground equipment that caters to many needs and is also fun for everyone”.

Fun is not a word users associate with many of the city’s playgrounds – the Leisure and Cultural Services Department manages 638 of them.

Playground users have a right to complain. Play is recognised as a fundamental right for every child under Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, and is essential for the development of children’s physical, cognitive and social skills.

Through play, children can practise motor control and coordination of body movements, learn about the physical world, and interact with others.

It’s beneficial for children with or without special needs to engage in physical and social play alongside one another. It also provides opportunities for parents to teach their children not to bully other children with either physical or invisible disabilities

Pau says the equipment at Tuen Mun is designed to stimulate the senses.

“There is a bird’s nest swing [or saucer swing] that offers therapeutic benefits through swinging back and forth and sideways. This enhances children’s spatial awareness and balance. The accessible swing seat offers children with limited physical mobility the chance to take part in the age-old activity of swinging while providing them with substantial head, neck, back and leg support.”

Another piece of equipment, a rotating climber, allows children to spin and climb simultaneously.

“Spinning helps with vestibular development (sense of balance) while climbing helps with the proprioceptive sense (sense of how one’s own body moves),” Pau says.

“When a child is in a playground, they are sending oxygen to their muscles while at the same time producing endorphins that have positive effects on their mood and activity level. Developing a strong sensory system creates a foundation for more complex learning later in life,” the study stated.

Pau notes that playing with sand and water allows children to interpret the world through touch. And getting messy is part of the process.

“While concern for hygiene is important, a lot of parents in Hong Kong do not let their kids engage in such ‘messy play’, although it can have immense benefits. Some kids have a heightened need for tactile input, while others avoid it. Messy play with water and sand allows them to develop better and to calm down.”

Numerous studies support that claim, showing “messy play” hones motor skills and hand-eye coordination while boosting muscle strength.

Playgrounds are also neutral public spaces that everyone has a right to access and enjoy, Pau says. “It’s beneficial for children with or without special needs to engage in physical and social play alongside one another. It also provides opportunities for parents to teach their children not to bully other children with either physical or invisible disabilities.”

Having more places where special needs families feel welcome, that are convenient and accessible so they’re not separated and segregated, is key to changing public perception, she adds. It gets across the message “that children with special needs are part of the community too, and that they should be treated with kindness”.