Cancer immunotherapy adapted to treat pet viruses could help humans fight infections, researcher says

- Using blood donated from a healthy cat, and building on a University of Hong Kong breakthrough, scientists inject lab-grown immune system cells in cats

- The immunotherapy cures an HIV-like virus that is otherwise untreatable, and shows promise in treating a feline virus similar to Covid-19. Humans could benefit

When news came in 2018 that the Nobel Prize in Medicine had been awarded to two cancer immunotherapy researchers, an idea flashed through animal-lover Yu Bin’s mind. The dog owner and former researcher with the School of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Hong Kong began to consider whether immunotherapy could be used to treat animals with diseases deemed incurable.

Together with a group of vets and medical researchers, Yu set up the Hong Kong Animal Diseases Research Fund to study immunotherapy treatments for animals with cancer and other diseases.

Yu says FIV mostly infects stray cats. “There’s currently no medicine to treat it. Pet owners can do nothing but give the sick cats health-boosting products for consumption,” he said. “Our treatment includes a shot per week in the first month. Depending on the condition of the cat, more shots might be needed,” he said. None of the cats his group treated has had a relapse.

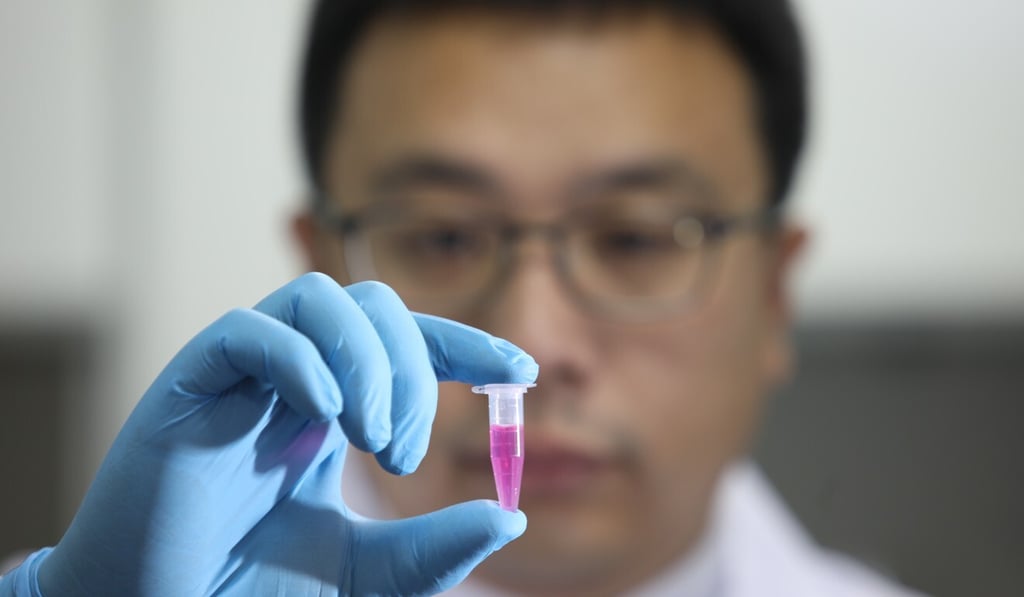

Like cancer immunotherapy for humans, which involves making immune-system-like substances in a laboratory to boost patients’ immune systems, the treatment developed by Yu’s group involves cultivating natural killer cells – a type of white blood cell in the immune system.