Advertisement

After 40 years of ‘grey area’ drinking, one woman quit alcohol, realised she’d been an addict all along – and at last understood why

- Professionally successful but personally unsettled, Robyn Flemming easily fell into the after-work drinking culture of Hong Kong, then added Xanax to the mix

- With April being Alcohol Awareness Month, she tells Kate Whitehead how she finally stopped drinking – and wrote about it in Skinful: A Memoir of Addiction

Reading Time:5 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

Robyn Flemming is a phenomenal woman.

Smart and well travelled, she is a sought-after editor and super social, gathering groups of like-minded people wherever she goes.

She is also 10 years and eight months sober.

Advertisement

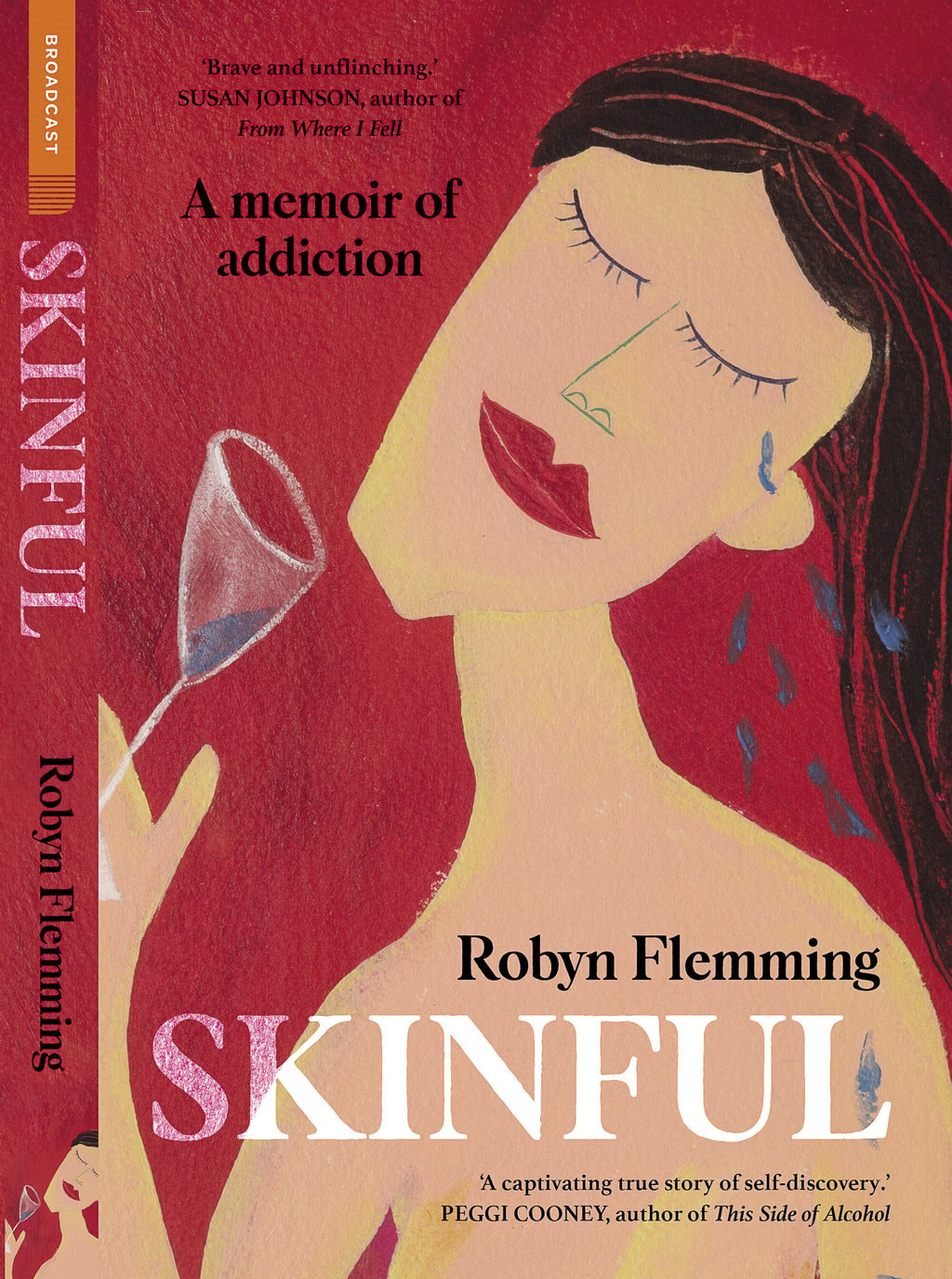

Now approaching her 70th birthday, she has her recently had a memoir published. Skinful: A Memoir of Addiction is her story of addiction and recovery, a good chunk of which is set in Hong Kong.

When she first approached publishers with the manuscript she was turned down because her personal story wasn’t bad enough, but that’s exactly what makes Skinful relevant – it is the story of everyday social drinking that slides down the slippery slope into “grey-area drinking”.

Advertisement

“This is a disorder, it’s on a spectrum like autism,” says Flemming. “There’s this area in the middle – grey-area drinking – where you’re drinking enough to worry yourself, even if you are still under the radar of the people around you who love you.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x