‘Like a light switch’: how sundowning syndrome affects dementia sufferers – and their carers; what it is and tips for how to cope

- Significant personality changes can beset dementia sufferers towards the end of the day; they may become angry, agitated, panicked and unable to sleep

- The syndrome may reflect a glitch in the circadian system that regulates sleep and emotions; an expert provides tips for alleviating its symptoms

It happens at roughly the same time of day: sundowning. But this is more than the slip of day to dusk. In the case of dementia, “sundowning” is the significant personality change that can beset sufferers towards the end of the day.

The person may become angry, agitated, confused, panicked, resistant to instruction and restless. In my mother’s case, she recently had a near-psychotic episode with hallucinations and marked distress.

Pummelling her stomach with a closed fist, she refused offers of help or fluid.

My mother can be so wired by these episodes that they prohibit her sleep, and ours. The last one kept her awake for 36 hours. We were all spent at the end of it.

“Nurses talk about it like almost a light switch,” says Trey Todd, a neuroscientist at the University of Wyoming in the United States. He says conservative estimates suggest about 20 per cent of dementia patients experience sundowning at some point.

It is often the reason families seek full-time professional care for their loved ones – a sort of final straw.

Sundowning as a syndrome – and not sunsets and sauvignon, which is what I once associated the word with – was first described in medicine in 1941 by British doctor Ewen Cameron, who called the condition “nocturnal delirium”.

He described patients who experienced disorientation, agitation and panic around bedtime.

The contemporary nickname, sundowning, was coined in 1987 by Lois Evans of Penn Nursing at Pennsylvania University, who is acknowledged as one of America’s leaders in care of the elderly.

But even though the phenomenon has been cited in medical literature for over 80 years, its underlying cause is still unknown.

Most researchers believe that sundowning reflects that something is amiss with the circadian system that choreographs our body’s natural processes – hunger, thirst, sex drive, body temperature, blood pressure and sleep.

It functions like a 24-hour clock, Todd explains.

“Down to the daily timing of the gene activity and electrical activity of its neurons, its output controls your daily rhythms,” he says.

When a person suffers dementia, the pathology of the brain changes and it throws this pace-making system out of whack, creating a “phase delay”. That means the peak of a patient’s daily activity comes later in the day than that of their healthy peers, and their body temperature minimum – when the rhythm is at its lowest point – is also later.

Sundowning typically starts in late afternoon or early evening, commonly between 4pm and 8pm, and clinical studies suggest that it occurs in middle-to-late stages of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia and gets worse with cognitive decline.

He posits that similarly, in humans, the circadian system normally makes us less reactive when we should be getting ready to go to bed.

It is a distressing disorder for sufferers and their carers but there are measures that you can take to alleviate its severity, Todd says.

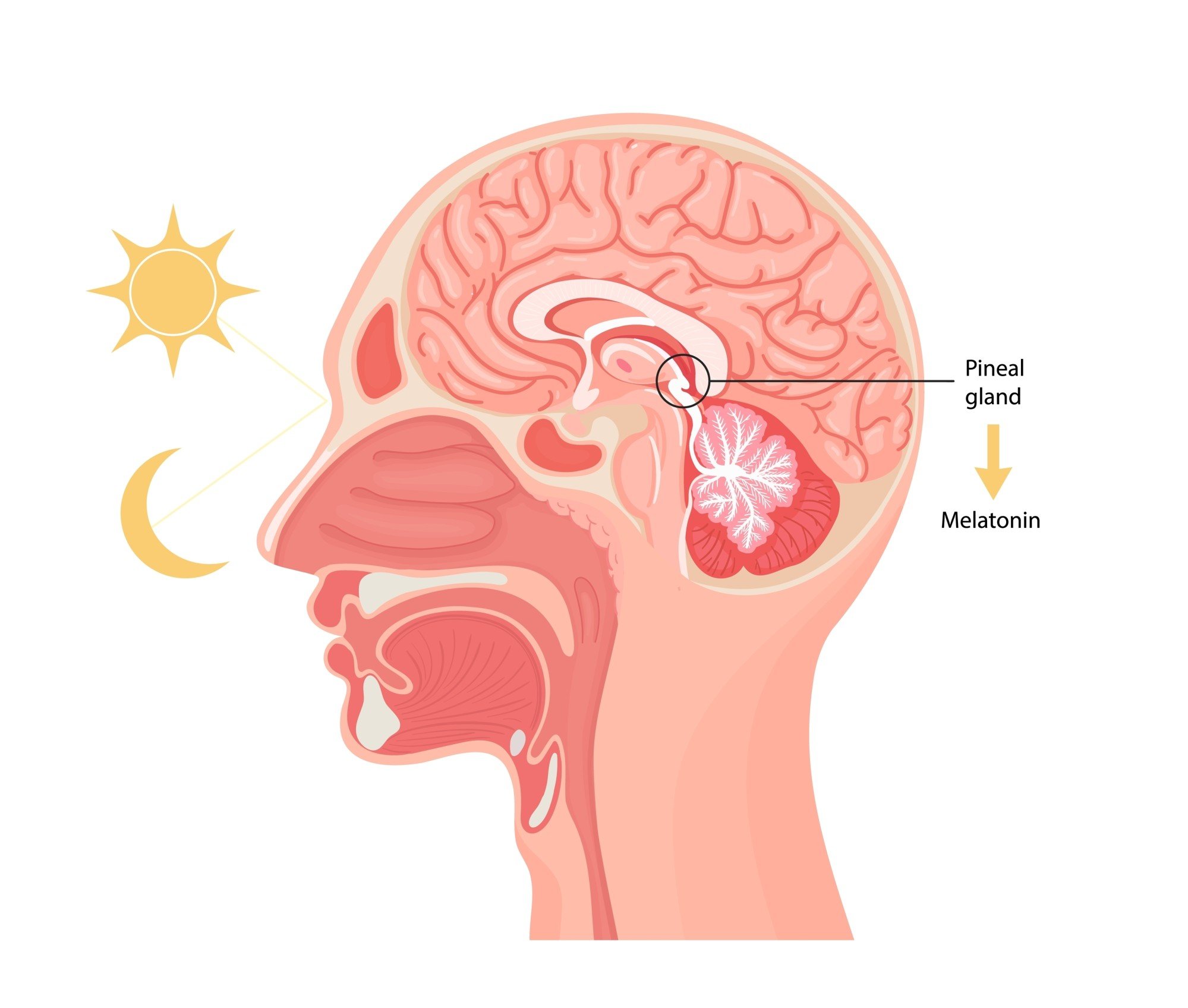

1. There is some evidence that melatonin supplements might help. The pineal gland in our brain produces melatonin, a protein whose production is triggered by darkness so, as darkness falls, we get more of it. As light occurs, it fades out.

It is what helps prompt us to sleep and awaken, supporting the healthy circadian rhythm. In a broken system, its production is disrupted. Age also interferes with this.

3. Bright light therapy during the daytime has been shown to be effective in improving rhythms and mood for dementia patients.

4. Getting out into the daylight early in the day is good for our sleep patterns, whether we have dementia or not.

5. Minimising the amount of light at night is important, as light may cause a worse phase delay, keeping the sufferer awake, Todd says.

I watch her behaviour closely in the late afternoon and if I think she is beginning to exhibit distress, I get her to bed earlier. That seems to have helped.

Finally, says Todd, “There is some interesting work that suggests taking a patient with sundowning for a walk at a consistent time each day, morning or evening, helps alleviate symptoms.”

I have definitely noticed that my mother is more agitated on the days when she has not walked.

With all of these measures, Todd says, “You are essentially giving the patient additional cues to help stabilise their timing and daily rhythms.”

In especially resistant patients, though, when episodes can be distressing for both sufferer and carers, doctors may prescribe medications which can include antipsychotics to help sufferers calm down and sleep.