‘An attack by aliens’: how to deal with a dementia patient’s delusions – experts’ tips for carers

- How does a carer best deal with a dementia patient’s distressing delusions and hallucinations? Don’t argue with their interpretations of the world, say experts

- ‘You have to go with the flow,’ says a neuropsychologist – by agreeing with a dementia sufferer and validating how they feel, you can manage a situation better

There were many things I found difficult about my mother’s dementia: her lost memories, the fact she did not remember I was her daughter, her faulty reasoning and her lack of concentration. And the fact we could hardly hold a conversation because she could not hold anything in her head.

The hardest things, the ones that saddened me most and caused her the greatest distress, especially near the end, were the paranoia, hallucinations and delusions she suffered.

None of these are unusual, says Professor Fiona Kumfor, a neuropsychologist at the University of Sydney in Australia, nor is the fact that carers are taken by surprise when they happen.

Memory loss is usually the most common early symptom of dementia, says Kumfor, “and it’s important people are aware of it”. But there is much work to be done to better understand the seeming breaks from reality dementia patients experience, and the behavioural changes that develop, as these have a bigger impact on families and carers.

Timothy Kwok, a professor of geriatric medicine at Chinese University of Hong Kong, agrees. Hallucinations are less common than delusions, he notes.

Delusions can be visual, like my mum’s were. But sometimes they can be auditory, in which someone hears things – and even olfactory, when they smell things – “like the house burning down, say”, explains Kumfor.

Believing things that are not real – the definition of delusion – happens because of a combination of factors, including cognitive and memory impairment.

As an example, if someone puts something down and forgets doing this, they might be able to rationalise where it may be. “But in somebody with dementia, the part of the brain that rationalises isn’t there any more, but they know there has to be an explanation for the fact of something ‘missing’.

“So they look for explanations. ‘I must have been robbed – that’s the only possible thing that can have happened.’”

Believing they are the victim of theft is common. My mum often fretted about who had taken “all her money”. She also worried we were trying to poison her. Kumfor is not surprised: persecutory delusions are especially common in Alzheimer’s disease.

Changes in the brain can cause visual misperceptions, Kumfor says. “It’s the brain playing tricks on senses we could once rely on. Sometimes something in the environment could trigger it: the light, shadows, the way the curtains move.”

She encourages carers to try to keep a diary of behavioural changes, “to see if there’s a pattern”.

The ability to recognise loved ones is often lost – as it was with Mum. And sometimes this loss of facial recognition is scrambled further as the rational part of the brain tries to bridge gaps; our rational brains might translate not knowing a face as having never met that person before.

“In dementia, it might translate as an attack by aliens,” Kumfor says.

These changes in perception can affect the most mundane scenario significantly, she says. Think about food on a plate. If a person is not eating as well as they once did, consider that it may be because they are not seeing the food on their plate as clearly.

“Avoid putting white rice on a white plate,” she suggests. “Instead try a blue plate; it could make all the difference.”

Another behavioural change which shook me was my mother’s loss of inhibition. She had always been so gracious and well-mannered, and was never outspoken or impolite. It was a shock when she articulated discontent or disgust with an uncharacteristic rudeness.

Disinhibition, poor control or restraint over emotions or actions, is common, says Kumfor – and it is another thing carers are less aware of. She likens it to being drunk.

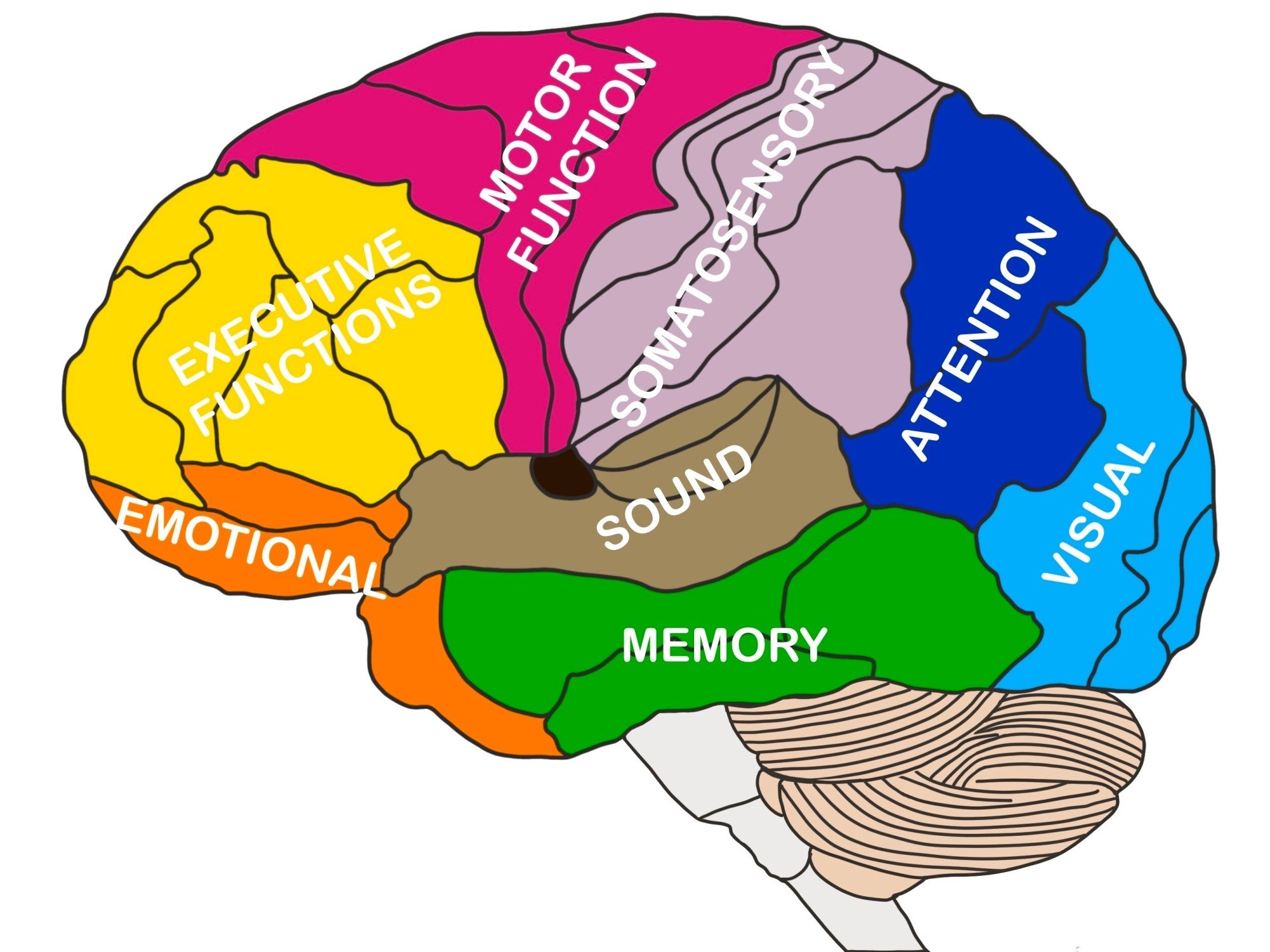

“When somebody has a few drinks, the frontal lobe does not function as well as it would normally. This is a part of the brain that is affected by dementia, so naturally the functions of that area are interfered with.”

How does the illness move through the brain?

Well, Kumfor explains, it begins in the memory centres, the hippocampus and the medial temporal lobe, then moves to other parts of the brain like the temporal lobes – the language centres – and then into the frontal lobe and the parietal lobes which process physical sensations.

In typical Alzheimer’s disease, memory is usually affected first and then language. Sufferers begin to struggle to find the right word, “that tip-of-the-tongue sensation”.

Then visual-spatial ability is damaged, which leads them to frequently get lost, which accounts for the wandering that some dementia sufferers do.

Then the prefrontal cortex is affected. It is the centre for executive function – the set of mental skills that include working memory, flexible thinking and self-control. Its impairment leads to disinhibition and delusions.

The area of the brain that is usually affected last is the bit responsible for motor skills. I knew this was under attack when my mother’s balance became so bad she could not stand without help.

At about the same time, she developed such bad tremors in both arms she was unable to feed herself, or raise a cup safely to her lips. A few days before she died, she lost the ability to walk.

How does a carer best deal with the distress of delusions and hallucinations? My mother’s paranoia was so disabling towards the end, her neurologist prescribed an antipsychotic, which helped.

Before that, though, I learned not to argue with her interpretations of the world. Kumfor says that was good instinct. “You have to go with the flow.”

Kwok explains why it is so important to do this, to “validate” a dementia sufferer’s beliefs. If they state something as fact, or if they want to do something, just agree, he says. After all, most of the time people are contradicting them.

“If you endorse what they believe, you’ll gain their trust.”

In gaining their trust, you will be able to manage a situation better. If they trust you, they are more likely to agree to look at a book with you, or join you in a cup of tea – and that means distraction.

“Once you get their attention focused on something else, the hope is they’ll forget about whatever it was you were trying to distract them from,” Kwok says, and they will become more calm.