At risk for Alzheimer’s disease? 2 new blood tests could detect it early – here’s how they do it

- New blood tests from Hong Kong-based Cognitact and US-based Quest could detect Alzheimer’s disease early, giving people a chance to work on interventions

- Both tests deliver an easier and cost-effective way to help form a diagnosis, but one doctor asks what support will be in place for newly diagnosed patients

In July, Cognitact, a biotech start-up at The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, launched PlasmarkAD, a blood test for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

The same month, US-based Quest introduced the first-to-market consumer-initiated blood test for AD risk assessment.

Both are blood-based biomarker tests.

‘Sepia galactic storms’: Alzheimer’s amyloid plaques and tau tangles

PlasmarkAD is a “groundbreaking” approach that goes beyond traditional biomarkers, says professor Amy Fu Kit-yu, from Cognitact’s team.

By analysing the levels of 21 plasma proteins, the test “captures the dysregulation of various biological processes and provides a comprehensive assessment of AD progression and severity”.

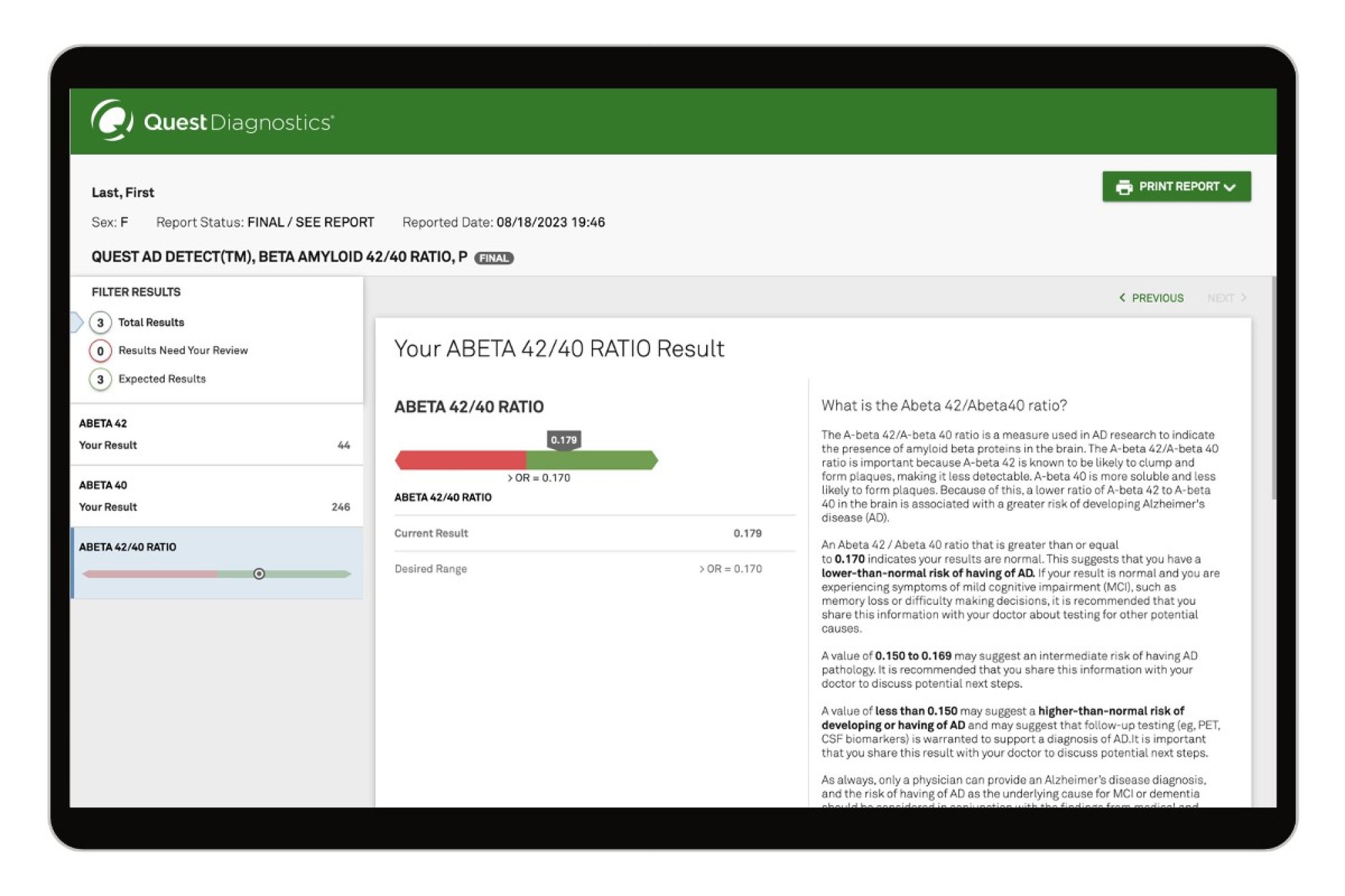

Quest’s test measures two peptides of amyloid protein; a lower ratio of one to the other in the brain is associated with a greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

These tests are a hopeful sign. They indicate that the science around this dreadful illness keeps moving forward. They also deliver an easier, less invasive and more cost-effective way to help form a diagnosis for AD.

Until now, diagnosis relied on costly MRI scans and time-consuming in-clinic cognitive tests, which can be unreliable. A patient may underperform if they are tired or feel nervous in a clinical setting, or they may disguise their limitations because they have learned to.

Timothy Kwok, a professor of geriatric medicine at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, describes a major advantage of the plasma test: it can detect early changes, before the onset of dementia, and even before brain atrophy changes can be seen on MRI scans.

It’s not just useful to confirm an AD diagnosis in those with dementia; it may also be useful in people with mild cognitive impairment, he says.

Another big advantage of a plasma test is that it assesses the contribution of different pathological brain changes, whether they are vascular or inflammatory or to do with immunity, Kwok says.

That means there’s a chance to change things – which leads to a more “personalised approach”.

Fu says PlasmarkAD is recommended for individuals with subjective memory complaints, those with a family history of AD, and individuals who are in middle age. (I check two of those boxes.)

As ageing is the primary risk factor for AD and dementia, Fu says, “undergoing this test during middle age can provide a baseline understanding of one’s brain-health status”.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association in the US, most people – up to 99 per cent – do not carry a genetic mutation for the disease. You may, however, carry a copy of the APOE-e4 gene, and people who do may bear an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

Dr David Merrill, an adult and geriatric psychiatrist and director of the Pacific Brain Health Centre at California’s Pacific Neuroscience Institute, agrees that blood tests may be more accurate at pointing to a diagnosis than taking medical histories alone.

But Merrill has concerns, some of which speak to my anxiety.

“What support will be in place for newly diagnosed patients?” he asks. “The diagnosis of Alzheimer’s can be a devastating moment.”

Know your family medical history: your health could depend on it

The brain changes associated with Alzheimer’s can manifest years before any symptoms present – and in some people, even in the face of pathological changes, symptoms never present.

“I think that pathology testing [for the proteins amyloid and tau] needs to be done as part of a larger framework of looking at neurodegenerative disease risk,” Merrill says.

Then, if the results point to the “protein misfolding” that is characteristic of Alzheimer’s, “it may be reasonable to check to see if you have something brewing”.

No cure for Alzheimer’s, but we can narrow the odds of developing it

If you do, you can start intervening in ways that have scientifically based mechanisms for addressing the problems.

Therefore, Merrill says, early testing before symptom onset could make sense within the context of knowing that the information can inform which interventions to prioritise.

Quest is careful to warn that its test – the AD Detect Test for Alzheimer’s Disease – is not a direct-to-consumer test and nor is it “diagnostic”. It can only be ordered for those patients who meet certain other risk criteria – including a family history of AD, evidence of mild cognitive impairment or head injury. They aren’t eligible for testing if they don’t.

And that’s a good thing – almost half of those who never exhibit any cognitive decline actually die with amyloid on their brains.

Dementia can’t be cured so why get a brain scan to check for it? Here’s why

Would I get a test – given my mother had Alzheimer’s and I’m hurtling towards 60? No. I wouldn’t.

There is no cure for this disease, and a result that suggested I was at risk would cause undue stress.

If at any point I become concerned about my cognitive function, then, and only then, would I seek a blood test for Alzheimer’s to open a window of opportunity for interventions that may slow its development.