Advertisement

Is cancer curable? Increasingly so, experts say – 5 reasons to be optimistic as big developments in treatment and diagnosis help more patients survive

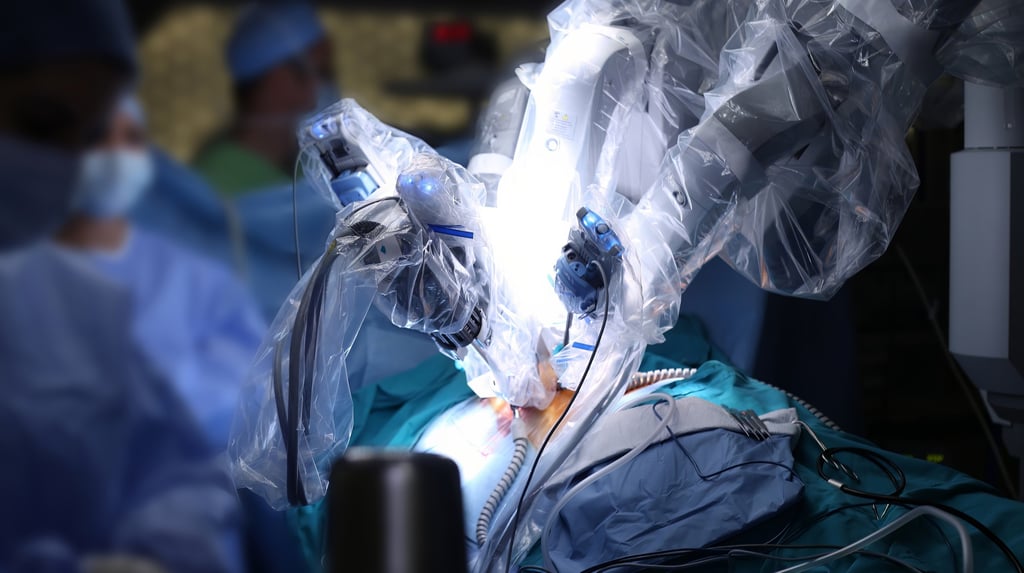

- Cancer, while still a leading cause of death, is becoming more curable with advances in treatment, from surgery to chemotherapy, and better drugs and testing

- Vaccines, such as for HPV, are playing a part, as is AI in aiding research. On World Cancer Day, doctors explain some of the tools being used to defeat cancer

Reading Time:6 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

An online news search for “recent” developments in the treatment of cancer returns 263,000 hits. It’s an area that is evolving – and fast.

A leading cause of mortality worldwide, cancer accounted for nearly 10 million – or nearly one in six – deaths in 2020. But it is less feared than it once was because there are so many more effective treatments than before.

In a paper, “A history of Cancer and its Treatment”, published in the Ulster Medical Journal in 2022, cancer specialist Dr Seamus McAleer wrote that when he entered the field of oncology in 1985, the 10-year survival rate for cancer in the UK was 25 per cent.

Advertisement

Today it’s over 50 per cent, a figure which McAleer believes will rise to 85 per cent in the next generation.

On World Cancer Day, February 4, cancer specialists describe some of the reasons for optimism about beating cancers of all types, including recent advances in treatment and research.

1. Stronger cancer treatment pillars

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x